Joe Milan Jr. on the Connectivity of Failure

“The thing that binds all writers together is that we fail, a lot, and often.”

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

The first time I got paid to write, I was 24, studying Korean at Kyung-Hee University in Seoul, and needed 500,000 won for a deposit on a moldy closet impersonating an apartment. The same day I found the apartment, I saw the flyer on campus announcing an essay writing contest in English. It had a separate category for foreign students like me. Being hopeful and listening to the whispers from the dim reaches of my skull, I saw it as my Magic Eight Ball moment: if I could pay for my apartment with my writing, I would be a writer. With that decision and 30 drafts of labor, I placed second and earned my deposit. I was a writer.

The first and third-place winners were no-shows to the ceremony and weren’t acknowledged. At the banquet, I asked the MC who they were.

“There were no other applicants,” he said, then slurped some noodles.

“But I got second place,” I said.

My face must‘ve contorted to something awful because he took one of those stern, appalled looks where lips thin. “Your essay wasn’t good enough for first place.”

All who have suffered under the dunce-cap-like “cone of silence” of workshop have felt failure’s barb.Sometimes, when I tell this story, I finish with, “I got second place in a one-horse race,” like one of those crystalline moral summations tagged onto an Aesop’s Fable. It’s a story to tell friends, and students, who sit in doubt and need to know that sometimes the success we seek isn’t the same thing as why we write. Stephen Marche does a good job discussing, in an abstract way, how pursuing money or proving those motherfuckers wrong isn’t why we write but to forge “ephemeral connections” to “alleviate a specific, minuscule cosmic loneliness.” Marche is also upbeat and right when he says, “Writing itself is failure. Even the successes are failures.”

All who have suffered under the dunce-cap-like “cone of silence” of workshop have felt failure’s barb as someone works up the courage to ask, “Is it believable to have a homeless Asian guy without explaining how he becomes homeless?” or “Is it appropriate to suggest that Trump and his allies are what happens when Hell’s cockroach demon representatives to the Republican party pile into the wrong clown car and don’t end up our reality and we instead get their bad tribute act?”

My mind likes specific failures. Like that sickening moment I had, trying to hold down nice Korean hweh (Korean sashimi), noodles, and the knowledge that I couldn’t even beat the idea of another writer. In workshop, our peers tell us our work fails to compel, fails to mystify. So, after being told our prose is weak with too many adverbs, our characters are “flat,” and “said” is actually punctuation, we decide that the way to get good is to emulate the successes. We read excerpts from Beloved, fawn over Joyce’s “The Dead”; Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants” is our guide to writing dialogue; we read their biographies and are comforted when we read about their struggles, like W.B. Yeat’s underlying “always” to the question, “Do you find that actual execution starts with a series of apparently futile attempts to work?”

But isn’t that true for everyone who writes, even those who don’t “get paid” to write? Even those who scribble on the back of receipts during a smoke break at Long John Silver or KimBap Country? Those people, of no fault of their own, never could get their stuff together to sling a manuscript that makes it through the machines to join the other, supposedly four million other, titles published each year? Yes, it is.

Writing itself is a failure. Seeing those futile attempts, those struggles for the perfect final line, the misspellings of words like heroes, would shine that universal failing light for all of us learning to write.

Writing itself is a failure.I take these flights of fancy because I’m lucky, or blessed, or loud enough and male enough and privileged enough to be alive at this moment and to be writing these words just days before my debut novel drops. Failure defines my narrator, and I think is the one “craft” thing that can be applied to all aspects of writing: prose surprises when the reader fails to anticipate its shape (the classic “but” turn of the line). Scenes move and end when the characters fail to get what they want (or at least how they wanted it). Books end well when the main characters get what they want but fail to get all they want. Writers fail in the telepathic message we think we’re sending from our slung words as the readers tell us that our books are really about hunger; our exes; or, insightfully, how systemic racism, sexism, and classism are poisoning the American soul.

So, I guess what I’m trying to say is that writers write for themselves and to connect and entertain others. Some are lucky and get paid, most don’t. But really, the thing that binds all writers together is that we fail, a lot, and often. All of us. And we love to talk about it. From shitty first drafts on, we ride with our failing characters, our failing lines of words, and hope we arrive at a timeline where it all works out.

___________________________

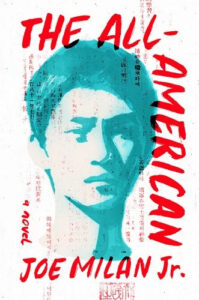

Joe Milan Jr.’s The All-American is available now from W.W. Norton.