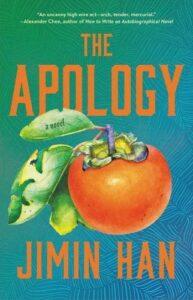

Jimin Han on Filling Narrative Blank Spaces With Memory and Imagination

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The Apology

Jimin Han’s The Apology features a straight-talking 105-year-old narrator and her centenarian siblings who travel to Chicago from Seoul for a wedding that shouldn’t happen because it uncovers a family connection long held secret. It’s a novel about how generations and siblings are separated by the war in Korea, and the experience of immigration to the U.S. Did she draw upon her own family background to build this story? “Separation is a theme that preoccupies me, absolutely,” she says. “My parents’ accounts of being torn from their families during the Korean War as children were talked about so often that I felt this kind of particular disaster was always an imminent possibility for me too. Not knowing is the part that is most painful for them.” Our email conversation took place in East Coast/West Coast time zones.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the past years of pandemic and tumult been for your writing, your life? How have the writing and publishing and launch of The Apology been affected?

Jimin Han: My husband and I have some health issues so while pandemic precautions have eased we still mask indoors. I hate that it’s continuing like this for us and so many others. When lockdown started I had no idea how much our lives would change. I’m home a lot more, feel more isolated. Focusing on the limitations of the body were top of mind when I was revising The Apology. The pandemic made it easier for me to think about Jeonga’s circumstances and how frustrated she might feel as a centenarian. Overall, for me now in my life, there’s more of an urgency to getting books written—some of it because of the pandemic and facing my own mortality after my mother’s death and the death of so many in recent years. My friend Brian Rogers died of brain cancer in 2021. He had so many books he wanted to write. I think about him a lot. In terms of promoting The Apology, the publishing team at Little, Brown has been very protective of me. Covid protocols are discussed with venues and they make sure I’m comfortable wherever I am. Masking makes it possible for me to promote the book relatively uninterrupted.

What isn’t said takes up space inside a narrative too. It’s what invites me to a page or blank screen.

JC: Your opening lines grab us: “Fleeing in a panic is not recommended. A week ago, my last day alive, I was at my grandson’s house in Chicago, America.” Why did you decide to open this novel with notice of the narrator’s death? And draw us at once into the ghostly realm as she narrates from the afterlife?

JH: In general I like to ease into things, whatever it is—which you wouldn’t know from both my novels. Hah! The credit for the beginning of the novel goes to my editor. She asked me to reconsider the original first chapter which began with Jeonga ruminating on epilogues, but after we talked I knew she was right. We understand Jeonga’s flaws and strengths much sooner with this change. Her enthusiasm for the new pages I submitted made me feel more confident about moving ahead with it and now I can’t imagine the book beginning any other way.

JC: Your narrator, Jeonga, is 105 years old when she leaves Seoul to travel to the U.S. to help resolve a complicated situation involving a family secret. Do you have a real-life model for Jeonga? How did you create her voice?

JH: With all that my parents talked about, there were other people and events about which they said very little. That fanned the flames of curiosity too. A memory of watching my grand aunt cry at her son’s gravesite has stayed with me all these years. My father said hardly anything about her but her clothes and her composure during that short encounter with her made me wonder about her and her life decades later. She would be 105 if she were still alive. What isn’t said takes up space inside a narrative too. It’s what invites me to a page or blank screen, the space to fill in with my own imagination. In terms of her voice, I guess I remember my own grandmother’s voice—she was my main caregiver until I was four years old—and have always found people in my grandmother’s generation fascinating. They lived through so much. I always asked my mother and aunt to tell me more about their mother.

JC: Jeonga has three sisters. Mina the oldest (110), Aera (108), the one who keeps track of “news about viruses and illnesses and scientific studies” and Seona, who she loved most and still misses (Seona eloped 89 years before; her husband and son came south during the Korean War, but she stayed in the north with her daughter). All three have strong dramatic roles in this novel. How did you develop their characters?

JH: Dialogue isn’t usually what I start with when I write but with these women, their chatter came first. They had so much to say so I wrote down their conversations like a script in early drafts. The rest of the details came easily after that about the places they were in and their gestures because it was all referenced in their conversations. I had so much material I had to cut a lot of pages. It was very necessary, but it was really hard to do because I wanted them to each be able to show who they were.

JC: How did you work out the details of Jeonga’s daily life as a centenarian—her clothes, her diet, her longtime aide Chohui, her emotional state?

JH: I confirmed some details about where someone like Jeonga might live and how she might have a young aide from my cousin who grew up in Seoul and who returns to visit her parents often, and I was in South Korea twice in 2016. But a lot of Jeonga’s very privileged life is drawn from my visit back when I was eighteen and spent the summer in South Korea. Since my mother didn’t travel with me, it was an odd experience to have a group of her childhood friends who were financially well off swoop in and take me to their luxurious homes and fancy restaurants. They were very kind to me but I was such a child to them and there was a language barrier though I understood more than they thought. As for humor, my mother and her sisters had a dry sense of humor that I hope comes through in the novel. One of the phrases that my uncle told me my aunt would say was never spit when you’re lying down looking up at the ceiling. She’d say this if she heard anyone criticizing another person. I think as writers we are a sponge for things like that, but I have to work hard to remember them. I’m constantly recording on my phone or trying to write phrases down in my notes app.

JC: The sibling rivalry in The Apology revolves around competing for status, bragging about their children (Jeonga’s only son died young), struggling to maintain a pecking order. How are the family ties maintained despite this ritualistic in-fighting?

I think as writers we are a sponge for things like that, but I have to work hard to remember them.

JH: Such a great question. In my mind, the sisters know how far they can push each other. And I think Seona’s absence has upset the balance so the three of them struggle now without her. Their history together is key. Their love of their parents and the childhood they shared are more important than their insecurities? I’ve seen people of all ages suddenly appear to be very young when they’re with their siblings or parents, but particularly siblings.

JC: Several plot twists reveal the secret Jeonga is keeping, beginning with the letter from Seona’s granddaughter Joyce, who is living in Chicago with a seriously ill son Jordan and needs financial help. This letter initiates the trip to Chicago by the sisters that leads to Jeonga’s death. Was it always part of your plot? How did you create it?

JH: It’s all about character, right? Jeonga is an avid reader of books and isn’t on KakaoTalk or any form of social media. I thought a letter had to be the only way she could be reached by Joyce in the United States. There’s the language barrier too. I worried at first that it was too much of a device—a letter—but then I thought the “how” is more important than the “what” that gets Jeonga’s quest started. I didn’t have to invent something new, the letter was right there—a way we still communicate and even more meaningful in some ways now that we’re all emailing and texting each other.

JC: Most of the book is narrated from the afterlife in which Jeonga is taught by various ancestors, including Seona, to interact with the living in hopes of righting a wrong for which she feels responsible. How did you research and construct this section of the novel?

JH: I’ve always been fascinated by shamanism in Korea and have done some research on it. Shamans are usually women. Also I was interested because my father always said we weren’t religious but then he and my mother had strong ideas about death in particular. I only discovered this by accident. My mother saw my driver’s license once and got upset that I’d agreed to be an organ donor. So we had a talk about all these ideas she had about the afterlife. And I realized there had been clues throughout my life about my mother’s beliefs. I’d considered them superstitions but they were more than that. They were more seamlessly part of how she saw life and death. I put some of those into the novel, and after her death I found myself drawn to KDramas and Korean movies about death to learn more about what she might have believed. It was particularly interesting to me to see which ones were popular in South Korea. Korean society is rather diverse in terms of religion so I thought there might be common threads in what people found moving. Hi Bye, Mama is a KDrama and the movies Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds and Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days were three that were notable, but I allowed myself the freedom to veer off and shape the narrative toward Jeonga’s hopes and fears.

JC: What are you working on next?

JH: I’ve had some enthusiastic support from my agent and my editor on a new manuscript. It’s very new and will take a while to develop, but it makes me hopeful. Facing a blank screen is always terrifying.

__________________________________

The Apology by Jimin Han is available from Little, Brown and Company.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.