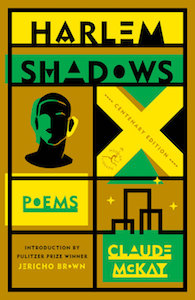

Jericho Brown on Claude McKay’s Subversive, Foundational Poems of Love and Protest

“In Harlem Shadows McKay used form to inscribe the fact of his own Blackness.”

By the 1922 publication of Harlem Shadows, Claude McKay was thirty-three years old and had already won the Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences’ Musgrave Medal for two earlier collections, Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads. In many ways, Harlem Shadows marked his maturity as a full-fledged Jamaican American poet at the same time that it was indeed the final book of verse published during his lifetime. McKay did not turn away from writing and publishing poems or from trying to print his poetry collections, but Harlem Shadows signaled the end of his identity as a poet specifically rather than as a writer in general.

Following Harlem Shadows, McKay went on to publish the famously bestselling Home to Harlem and several other novels; two autobiographies; a volume in Russian on race, racism, and communism; countless articles as a radical journalist (some of which were published under pseudonyms for the sake of his safety); and several speeches and letters that historians and scholars now use to gain a better picture of the times in which McKay lived.

The book you hold in your hands, then, is a transitional text in the life of a singular artist as much as it is the volume that cements McKay’s position as a foundational poet in the literary movement we now know as the Harlem Renaissance. What distinguishes McKay’s poetry, in this time of diverse and abundant work, from that of so many other Black writers is its attention to and subversion of traditional forms in spite of (and maybe because of) the Modernist rejection of them, a preoccupation with the individual as a being made possible by the community and the community made possible by individuals who are aware of it and love it, and the need to show Black people (including himself) as they are and not as propaganda would characterize them for the sake of acceptance by white people.

Though some scholars think of Harlem Renaissance poets’ work as contradictory to the tenets of Modernism and to the work of the major white poets of the time, McKay is proof that this is quite misread. Like any other educated English speaker at the turn of the century, McKay centered his literary studies on the work of British writers, which is to say that his first poetic influences most likely spanned Shakespeare to John Keats and all the other white men in between. Like so many readers, he learned that the well-wrought sonnet is the mark of true achievement for any poet. And he learned to understand the sonnet as the form so often used for love poetry, for the unrequited desire a lover has for a beloved.

What distinguishes McKay’s poetry, in this time of diverse and abundant work, from that of so many other Black writers is its attention to and subversion of traditional forms.

But McKay’s own sonnets in Harlem Shadows are anything but love poems in the Renaissance or Romantic sense. As a matter of fact, several of the more than thirty sonnets characterize rebellion, distaste, and protest, going as far as to make use of the word hate in order to subvert our ideas of what the sonnet is and can do. At the time when Modernists were rejecting form in favor of free verse, McKay used form to inscribe the fact of his own Blackness and the existence of real-life, feeling, thinking, and reading Black people, thereby interrogating the value of the form itself. Is the sonnet somehow less an achievement when a Black man makes one? Is the sonnet an achievement at all if it does not speak to one’s moment as much as it might speak to one’s romantic desires?

The book’s first sonnet, “America,” begins: “Although she feeds me bread of bitterness, / And sinks into my throat her tiger’s tooth, / Stealing my breath of life, I will confess / I love this cultured hell that tests my youth,” and further confesses, “Yet, as a rebel fronts a king in state, / I stand within her walls with not a shred / Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer.” The speaker loves the “hell” that murders him, and that hell is a nation; what was once traditionally cast as unrequited through the form becomes more physically dangerous and causes more mental anguish than sonnets heretofore seemed capable of bearing. This is not simply angst. In “The White City,” hate becomes an energy the speaker uses to survive:

Deep in the secret chambers of my heart

I muse my life-long hate, and without flinch

I bear it nobly as I live my part.

My being would be a skeleton, a shell,

If this dark Passion that fills my every mood,

And makes my heaven in the white world’s hell,

Did not forever feed me vital blood.

In contrast to other Harlem Renaissance poets, McKay always used the form personally and directly rather than archetypally and subtly. His contemporary Countee Cullen, at the end of the sonnet “Yet Do I Marvel,” moved to third person, wondering why God would create Black poets at all after rendering creatures in nature like a mole and popular figures in Greek mythology like Sisyphus. And in the formally innovative blues of Langston Hughes, we seem to read what must be taken only as persona when he wrote in the voices of biracial speakers alienated from both sides of their families or of dead speakers who have committed suicide as a reaction to a romantic breakup.

Claude McKay, on the other hand, developed a speaker who always seems to be the direct witness of an experience or the one who’s had the experience firsthand. One of the best examples is “The Harlem Dancer,” which—along with being a tour de force in the manipulation of metrical pattern and variation—is a kind of ars poetica that allows the poet to see his own position among his people through looking at another artist in a similar position. The poem ends, “The wine-flushed, bold-eyed boys, and even the girls, / Devoured her shape with eager, passionate gaze; / But looking at her falsely-smiling face, / I knew her self was not in that strange place.”

This final move is one ambition of all McKay’s poems. He means to make real the Black people of his community and to name himself a part of that community. And he doesn’t care if those characters are “wine-flushed” or, as in the title poem, “girls who pass / To bend and barter at desire’s call.” He can’t be concerned about the class or supposed moral standing of these people, as he sees himself as one of them. Just as “The Harlem Dancer” ends in a revelatory moment of understanding, “Harlem Shadows” concludes, “The sacred brown feet of my fallen race! / Ah, heart of me, the weary, weary feet / In Harlem wandering from street to street.” And of course, the very famous and enduring “If We Must Die” proceeds in the first person plural. It is a perfect poem that manages to make its speaker an entire people.

While “If We Must Die” will ever be known as the preeminent protest poem, I have always thought of Harlem Shadows as a book of love poems.

Still, McKay was not a writer of the monolith. The end of “The Tropics in New York” is not a mistake of sentimentality but a purposeful risk of sentimentality. “I turned aside and bowed my head and wept” reminds us of our own personhood, our ability to miss home, which is not contradictory to anyone’s ability to speak truth to power. Because McKay did not work in dramatic monologue, the final third of Harlem Shadows—a series of erotic and elegiac love poems—reaches the height of its complexity and daring with “One Year After,” probably one of the earliest first-person poems on the difficulties of being a Black person in the midst of an interracial love affair, and one that appears to be autobiographical: “That even I was faithless to my race / Bleeding beneath the iron hand of thine, / Our union seemed a monstrous thing and base!”

I mention courage, admission, confession, and the complexities of love in a nation that will not love back because it cannot love Black because these are the themes and concerns I knew I could handle in my own work only after reading the work of Claude McKay. While “If We Must Die” will ever be known as the preeminent protest poem, I have always thought of Harlem Shadows as a book of love poems. It’s a book about an immigrant man who misses home but means to make it as a writer in this nation and believes he needs the unity of his people to do it.

And though scholars argue over whether these poems make clear McKay’s queerness—he was bisexual, frequented gay venues and parties, and had erotic relationships with both men and women throughout his life—it is always important for us to remember that none of these poems would have been written if he had not been queer. All art is the product of the entirety of an artist’s life, whether that art is biographical or confessional or neither. I cannot imagine how I would have ever known to write my own poems had Claude McKay not written his.

________________________________________________________________

Introduction by Jericho Brown to a new edition of the book HARLEM SHADOWS by Claude McKay. Introduction copyright © 2022 by Jericho Brown. Published by The Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Jericho Brown

Jericho Brown is author of the The Tradition (Copper Canyon 2019), for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. The Tradition also won the Paterson Poetry Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is the director of the Creative Writing Program and a professor at Emory University.