Jenna Clake on Learning the Craft of Fiction By Working In a Call Center

"I’ve found that writing preoccupies me during challenging days when I feel little motivation for anything else."

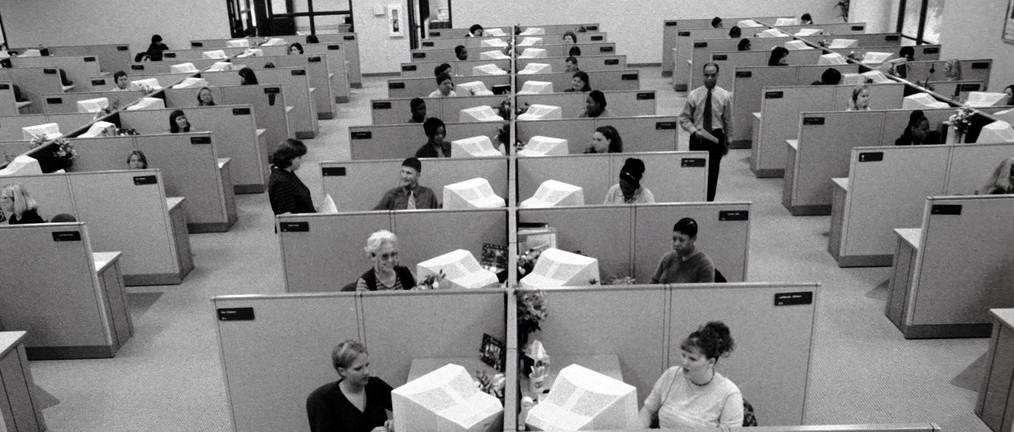

In my early twenties, I worked in the call center of an energy supplier, answering phones and emails. The work was exhausting, and extremely high-pressured. I often heard the telephone’s shrill ringing in my sleep, and had nightmares about malfunctioning spreadsheets, or messages I’d forgotten to answer, an endless ream of pings and rings and demands.

There are many novels about young women at work. Millie, the thirty-year-old protagonist of Halle Butler’s The New Me, desperately tries to “assess the things that bring me pleasure and how those things might bring me a fulfilling career.” The answer sits in her “empty skull: nothing, nothing, nothing.” While Millie daydreams about being assertive and proactive, she realizes she is sitting at a desk to “slowly [collect] money that I can use to pay the rent on my apartment and on food so I can continue to live and continue to come to this room and sit at this desk and slowly collect money.” After suffering a breakdown, the narrator of Kikuko Tsumura’s There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job wants a job that is “practically without substance, a job that sat on the borderline between being a job and not.” Jobs, she notes, cannot offer stability: “Whoever you were, there was a chance that you would end up wanting to run away from a job you had believed in.” In Madeleine Watts’s The Inland Sea, an Australian woman spirals, falling into self-destructive behavior as she prepares to leave Sydney for Los Angeles. She begins working as an emergency call responder, a job which only compounds her self-destruction, her days punctuated by the refrain: “Emergency police, fire, or ambulance?.” The disjunction between what she hears on the calls and the unemotive, repetitious nature of the call center script feeds her growing sense of detachment from the world. As she answers the calls, the narrator keeps a notebook, writing down ideas, but never finds time to come back to them.

The women in these novels are burned out, and use work as a space in which to hide from their personal lives, to wallow in their stasis, or to recognize, without impetus, the repetition of their lives. They shirk expectations of productivity, realizing that work is meaningless, or they recognize that their offices are worlds in themselves, consuming, unhealthy, microcosms of what is wrong with society. Like the women in these novels, the narrator of my own novel, Disturbance, uses office work as an emotional void to escape the pressures of her personal life. When she needs to escape from her memories of her abusive ex-boyfriend, she is consumed by spreadsheets and emails, the “logical and unemotional” work acting as a balm for her trauma.

I have found that dedicating myself to working out details of plot, character and descriptions has the same sense of escapism as the absorbing administration.

I gave my narrator my old job, except there is no buzzing, hot, frantic call center—just her flat, haunted by an unsettling and menacing presence, which may or may not be her abusive ex-boyfriend. The narrator’s isolation is compounded by the fact that her office has been closed—”part of a nationwide trend to save money”—and this makes her keep “strange time,” working into the night until she collapses on her bed in the early hours of the morning, unable to keep her eyes open. From my time in the call center, I know this pattern of over-working, anxiously thinking through problems, scribbling down ideas when I should be sleeping. The narrator’s favorite part of the job, getting “lost for hours trying to resolve mixed-up meters on the national database” was my favorite part of the job, too. While such problem-solving work distracts the narrator from thinking about her ex-boyfriend, when I worked in the call center, I relished shutting out the rest of the world and sinking into some administration; for me, there was no better respite from my thoughts about where my life was going, and who I might become, than a report or complex complaint.

The women in the above novels cope with their workplace existential dread by creating meaning in their lives (however misguidedly)—through friendships, new interests, love affairs or re-inventions. So, eventually, my narrator’s work obsession gives way to a fixation on the occult and her teenage next-door neighbor, Chelsea, and her best friend, Jess. My narrator soon ignores “the ping of emails flooding my inbox,” indulging her new interest in witchcraft, trawling the Internet for hexes and spells. To make meaning in her life, the narrator moves away from the emotional void of her job and begins to dabble in the occult, hoping that it will banish her ex-boyfriend.

If it is true that the narrator’s distraction techniques mirror my own, then it is also true that her attempts to find meaning in her life are inspired by my need to move away from the emotional void of work. And, when I worked for the energy company, I created meaning in my life by writing. In the call center, I spent most of my day in a plastic computer chair, straight-backed and alert, being shouted at by customers about bills, or by a team leader for not taking enough calls. Eventually, the emotional void wore thin, and I began to feel like I was living through a series of rehearsed phrases and actions spoken, typed out, and clicked.

When I finally made it home, or to the weekend, I found the best place to write: lying down. At home, reclined and sprawled across my bed, I balanced my laptop on my stomach, or on my chest if that became uncomfortable. Propped up on some pillows, surrounded by books, I started to feel more like myself, able to think creatively, beyond spreadsheet cells, and to imagine things, to inhabit other worlds. Even now, I continue to write lying down on my sofa or my bed because it feels the opposite to being at work. I tried back then, and have continued to try, to write at a desk, but it feels too much like doing administration. When I sit at a desk, I think: emails, spreadsheets, reports. When I lie down, the hum of the day fades away, and all my worries about work or my life become muffled by my ideas.

I have found that dedicating myself to working out details of plot, character and descriptions has the same sense of escapism as the absorbing administration, but with significantly less existential dread—perhaps because writing a novel has a logical endpoint, and thereby a goal to work towards, and working in a call center does not; the calls keep on coming. As the narrator of Disturbance searches for something that will shut out her anxiety and terror, and give her a sense of meaning, I’ve found that writing preoccupies me during challenging days when I feel little motivation for anything else, or I need to switch off from other worries. Then there is just me—the creative me—my keyboard, and a blank page.

__________________________________

Disturbance by Jenna Clake is available from W.W. Norton & Company.

Jenna Clake

Jenna Clake is the author of two collections of poetry, Museum of Ice Cream and Fortune Cookie, which received an Eric Gregory Award and was shortlisted for a Somerset Maugham Award. She lives in Newcastle upon Tyne, England.