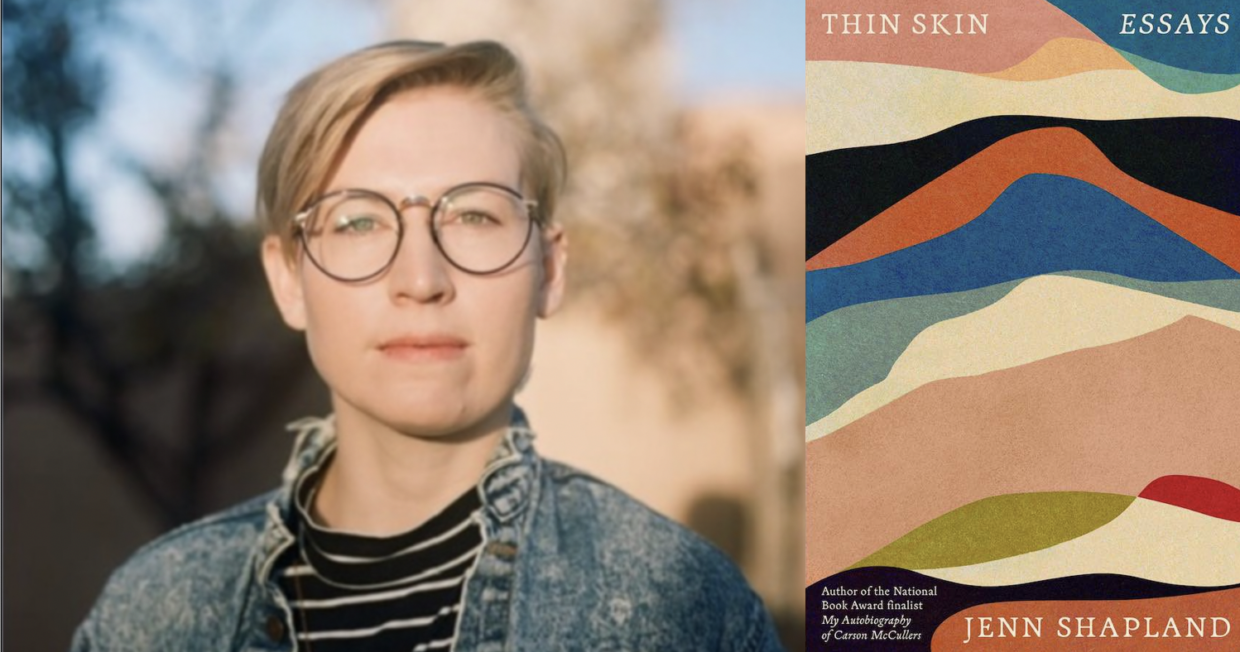

Jenn Shapland on Santa Fe and Fear of Cities

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

This week on The Maris Review, Jenn Shapland joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Thin Skin, out now from Pantheon.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

MK: Tell me about the city of Santa Fe as a backdrop for this collection.

JS: I moved here seven years ago with Chelsea from Austin after graduate school. And you know, Austin had really changed in the time we both lived there dramatically. And a lot of cities are going through that same change, where kind of the tech industry comes in and everything is transformed and sort of overrun, and suddenly the city is completely different.

We wanted to live in a place where there was less of a chance of that happening. And we wanted to live in a place that was a little bit smaller, a little bit quieter. Santa Fe is all those things. It is really unique and strange and kind of a bubble unto itself, but in terms of a place where, if you’re trying to pursue creative practice or creative work, it’s really conducive to that. No one’s really asking what do you do for a living? Everyone’s kind of interested in what you’re working on. Or they’re just really deep into their hobbies. I was at my friend’s house picking peaches this morning and they have like a little hobby farm. It’s like that kind of a place, which I really appreciate.

And so, as a backdrop for the book, it did become important. I describe it as a woo paradise at one point because certainly there are many different forms of healers who’ve flocked to Santa Fe and Santa Fe has a long history as a place where people come to be healed. I wrote an essay that’s not in the book, but that was about the history of the tuberculosis sanatoriums here, and how Santa Fe came to be understood as this place of retreat or a place for artists and writers to kind of escape.

There are problems with that narrative, too. There are ways in which that narrative is often about white people moving in. It’s often a colonial narrative. It really can discount the perspectives of the native people, the Pueblo people who’ve been here for centuries, of the Hispanic people who’ve been here for centuries. So it’s a place with a really complicated and living history. That’s a negotiation that I find to be happening in real time all the time. I appreciate that, too. That there are these conversations that are kind of ongoing within the city and among these different groups.

Whereas, you know, where I grew up, for example, Chicago, is one of the most segregated cities in the country, and it’s not something that in my suburb was discussed. It was a reality we lived within, but it wasn’t something we talked about. I hear people talk about it, which I appreciate.

MK: I really identified with that aspect of growing up in suburbia and watching the evening news and feeling so much fear. It took me years of living in a city to realize that that might have been manufactured.

JS: Right, right. “Strangers on a Train” is really my reckoning with some of the lingering aspects of that fear. The sense that when I take the trash out at night, why am I like watching over my shoulder and a little worried like, what is that? Where does that come from? And I really do feel like it comes from those very early memories of being made to feel vulnerable and fragile. And that was something that was coming through the news, like you mentioned, the evening news. And then it was also coming from my parents and it was coming from the rest of the community.

This idea that, no one’s saying this part out loud, but that as a white girl, I needed to be protected and I needed to not be exposed to certain realities. And that was what the whole town, the whole suburb existed to protect, uh, in this way. And then that kind of just lingers. And if you don’t find a way to examine it, question it, and reckon with it, it could really shape your behavior. Even as an adult, right? And so, yeah, as I sort of started moving through the world as an adult, specifically trying to travel on my own and camp on my own, suddenly coming up against, okay, what is this fear? I can’t stop fear, fear’s a very fast moving emotion in our brain, but, I can at least pause and say, what is that? And is that real? Do I need to believe that? And then, you know, progress from there.

MK: It does feel broader, like we were, basically, or I was, at least taught not to trust strangers.

JS: Right.

MK: Let’s talk a little bit more about “Too Muchness” before we get to “The Meaning of Life,” which is the name of the essay, not just like a thing we’re gonna talk about. You touch on this so well, but minimalism is so calming and aspirational, and I am saying this from my 800 square foot apartment in Brooklyn where you can see we are not minimalist here. Tell me about putting that together.

JS: Yeah, I mean in the too muchness, I’m writing about excess, so I’m writing about shopping, but I’m also writing about accumulation, like what it feels like to have a bunch of clothes that you can’t wear. All of them that, in my case, were being eaten by moths that represented really old and dormant or no longer useful aspects of my personality or my identity or my gender expression.

What do we do with all this stuff? Well, the flip side of that and something that you really find if you look at any kind of design magazine or website is minimalism, right? Is like an empty white space. And it struck me, you know, the link there between minimalism between those spaces and whiteness and white supremacy.

So I dig a little bit into Anna Chaves’s work on middle minimalism and specifically minimalism and art. And what some of the artists, for better or worse, were thinking and believing about the way their work at that time could operate in the world. Kind of apart from politics. And this is the 1960s, so it’s a moment when everything is political, and these certain artists who are for the most part, white cis men decided oh, we could make work that stands apart from all that.

And that can be In this blank white space on its own. And, you know, thinking about those spaces, the line that comes to mind is Claudia Rankine and she wrote “At the bone of bone white breathes the fear of seeing.”

So this idea that somehow inherent in whiteness is this desire not to see or not to engage, and you find that very much if you start looking on the internet for people talking about wanting to purge themselves of their stuff. They’re like, I just don’t even wanna see this anymore.

And so that kind of led me to make the connection. Okay, so there’s a guilt here. Maybe there’s white guilt, but there’s also some real material guilt around the stuff that we’ve acquired and how it makes us feel. There’s a desire to just get rid of it that goes beyond creating a minimalist space. It can even lead to wanting to have a bunker and wanting to imagine the end of the world. And the end of the world is kind of like the ultimate minimalist vision. And then you could live on in that empty blank space. And all of that is so deeply connected to complicity, like you were talking about at the beginning, to this belief that we have wrought something terrible and it, it is in some way our responsibility.

*

Recommended Reading:

How To Break Up With Your Phone by Catherine Price • Thick by Tressie McMillan Cottom • Festival Days by Jo Ann Beard

__________________________________

Jenn Shapland‘s first book, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, was a finalist for the National Book Award and won the Lambda Literary Award and the Publishing Triangle Award. Shapland has a PhD in English from the University of Texas at Austin and she works as an archivist for a visual artist. Her new essay collection is called Thin Skin.