Jeff VanderMeer on Keeping Creative Play Alive

"Different forces are at work today with regard to the imagination."

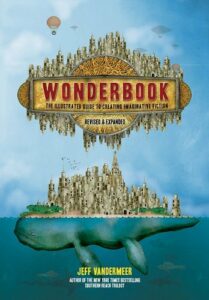

The following is excerpted from Jeff VanderMeer’s Wonderbook (Revised and Expanded): The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction and first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Bears figured prominently in our own household when my stepdaughter was growing up, invoked through the trickster aspect of our relationship. I had been feeding her lines of what one can only call tall tales or creative hogwash. For example, she would find a letter under her pillow from the “frog fairy,” not the tooth fairy, with a couple of Chinese coins enclosed. The letter apologized for a lack of US currency and explained that the exchange rate for teeth wasn’t favorable right now. Finally, she decided to get back at me. She knew that I, an agnostic, was trying to learn more about her mother’s Jewish faith. So during our first holiday season together she told me all about the glory that was the “Hanukkah Bear,” and I wound up reciting these “facts” to the rabbi at my wife’s synagogue — only to find out, much to everyone’s amusement, that she had “punked” me. I wasn’t mad at all; instead, I was impressed by the quality of her imagination.

When unburdened by the need to put words on a page, the imagination often appears as a form of love and sharing: playful, generous, and transformative. The best fiction is often driven by this invisible engine, which hums and purrs and sighs.

Different forces are at work today with regard to the imagination. Modern ideals of functionality and the trend toward seamless design in our technology have taken the very human striving for perfection and given us the illusion of having attained it (which, ironically, seems very dehumanizing). In this environment, some writers second-guess their instincts and devalue the sense of play that infuses creative endeavors: “This antique Tiffany lamp must provide light right now, even before I screw in the lightbulb and plug it in, or it’s worthless.” At best the imagination can be seen as heat lightning with no real weight or effect, instead of the source. At worst, it’s dismissed as frivolous and a waste of time, with no real-world applications.

To some extent, I understand the reasons for this attitude. Creative play speaks to an aspect of the imagination that defies easy measurement. It brings yet another level of uncertainty to an endeavor already saturated with the subjective. That truth can make writers and readers alike uncomfortable. The world wants to believe in technique and craft, in practice and hard work as the primary ingredients of success.

Inherent in this idea of “play” being immature and frivolous is the idea that, just like business processes, all creative processes should be efficient, timely, linear, organized, and easily summarized. If it’s not clearly a means to an end, it must be a waste of time. In the worst creative writing books, this method is expressed in seven-point plot outlines and other easy shortcuts rather than as exercises to help encourage the organic development of your own approach. This kind of codification sometimes reflects a fear of the uncertainty of the imagination and the need to have a set of rules in place through which to understand the universe.

In considering the worth of “fantasy” and “science fiction” — modes of fiction still perceived as valuing concepts and settings over characters — this sense of imagination being “frivolous” is allied to society’s ideas of what is “serious” versus what is “entertainment.” Fantastical writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, Jorge Luis Borges, and Italo Calvino might be inextricably intertwining play with their exploration of complex intellectual ideas, but this aspect is often ignored in reviews, perhaps because it is considered irrelevant to the “point” of good fiction. Instead of being essential, core, inseparable from.

The word “frivolous” lurks in the subtext of such opinions, along with the assumption that flights of fantasy have no moorings to reality, a tether believed by some to be essential. Yet completely un-utilitarian fantastical “documents” like the famed Codex Seraphinianus (created by Luigi Serafini in the 1970s), the mysterious 15th-century Voynich Manuscript, or writer-artist Richard A. Kirk’s “Iconoclast” imaginings have a marvelous intrinsic value no matter what we can actually glean from them. Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland may or may not include some interesting life lessons, but that is beside the point of the mathematical precision of its frivolity. As the award-winning Australian writer Lisa L. Hannett points out, “‘frivolous’ reading is as important as creative play. Reading for fun, reading to feed your imagination, reading to revel in the childlike wonder of being elsewhere.”

Whether accepted by the mainstream like Alice or kept on the fringes like The Codex, these creations are among the greatest examples of pure imaginative play in fantasy. The Codex’s encyclopedia of images and text of an imaginary world, written using an invented language, has no practical value at all. The Voynich Manuscript, also written in a language no one has been able to decipher, contains botanical and astrological sections that are clearly fantastical no matter what the actual purpose of the document. It, too, exists for its own sake. Kirk’s “Iconoclast” series has perhaps a more practical point to make, but just barely. It posits a strange alternate universe in which language is expressed through complex images. As a result, even the most basic communications take weeks; but since the participants “speak” in different styles, understanding is rudimentary at best and wars break out over inadequately expressed paintings. All of these ultimate expressions of the imagination share one thing in common, however. By existing at the outer edges of practicality, they expand the range of the possible for the rest of us.

But this idea of the fantastical imagination being unmoored from reality causes issues, too. It spreads the lie that fantasy has no causality, and it implicates the imagination in this crime. The subtext is that in fantasy fiction the sense of play that surrounds the fantastical and leads directly to creation needs less shaping somehow — as if the attempt to convey an ordinary reality is more complex and messier.

Even the issue of what is imaginative or fantastical can be misunderstood, especially by those who are overinvested in the tribalism of genre. Does it really matter if the imaginative impulse results in the “fantastical” in the sense of “containing an explicit fantastical event”? No. For one thing, “imaginative” writing occurs across every possible genre and subgenre. And for a certain kind of writer, a sense of fantastical play will always exist on the page.

When I asked one of our greatest writers, Haruki Murakami, about the surreal aspects of his work, he said, “It’s not that I’m trying to introduce into the story surrealistic things and situations that I became aware of. I’m just trying to portray things that are real to me, myself, a little more realistically. However, the harder I try to realistically portray real things, the more the things that appear in my work have a tendency to become unreal. To put it another way, by viewing it through an unreal lens, the world looks more real.”

*

Read more on creative life:

Roxane Gay on the critical role of imagination right now.

Mary Gannon and Kevin Larimer on how having a writing community stimulates creativity.

Evan James on the value of “how to” books for creativity.

Helen Betya Rubinstein on changing the way creative writing is taught.

__________________________________

From Wonderbook (Revised and Expanded): The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction, by Jeff VanderMeer © 2018, published by Abrams Image.

Jeff VanderMeer

Jeff VanderMeer is the New York Times bestselling author of more than 20 books including novels and fiction anthologies. He has won the Nebula Award, the British Fantasy Award, and, three times, the World Fantasy Award and has been a finalist for the Hugo Award. He is the cofounder and assistant director of Shared Worlds, a unique fantasy and science fiction writing camp for teenagers. He lives in Tallahassee, Florida.