“Opening bookshop in Paris. Please send money.”

“Opening bookshop in Paris. Please send money.”

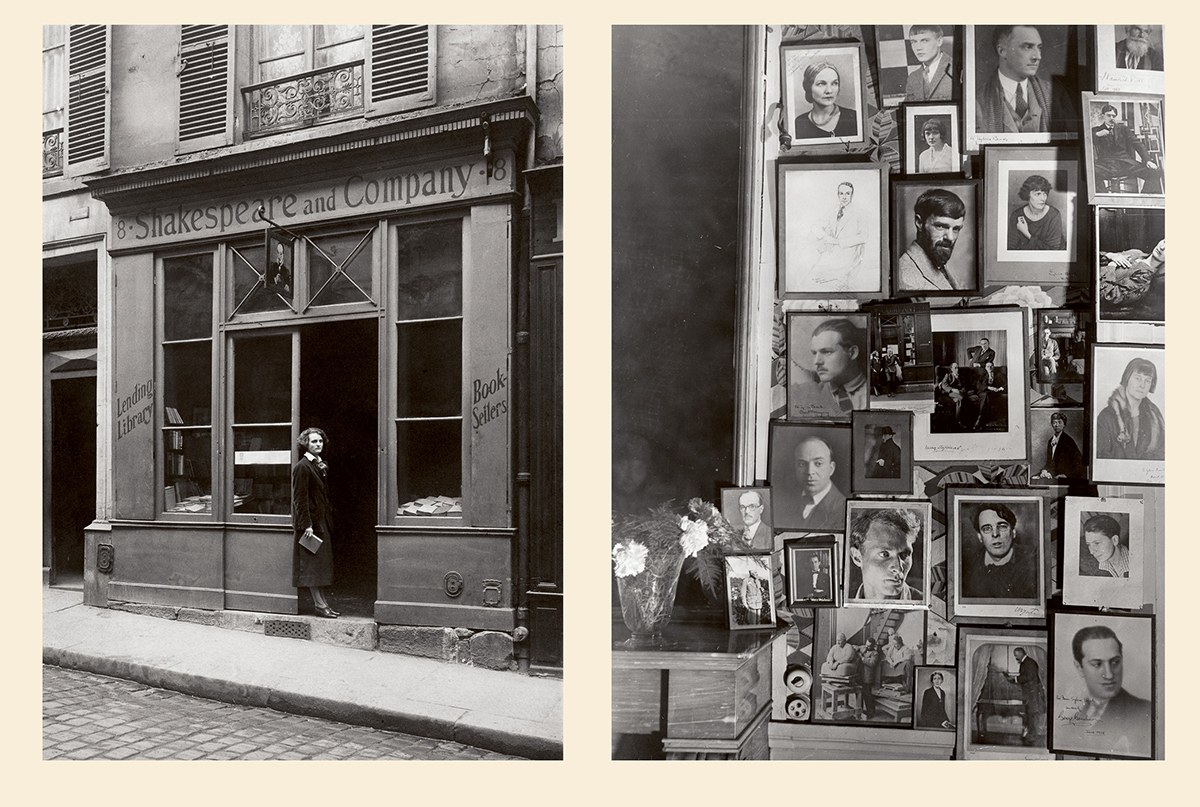

Every story starts somewhere—this one begins in 1919 when Sylvia Beach, from Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A., opened her shop, Shakespeare and Company—the most famous bookstore in the world.

There’s Hemingway, flexing his fists from the boxing ring, stopping by to pick up a book. James Joyce never arrives before noon and usually needs to borrow money. The big woman with the white poodle is Gertrude Stein. By the stove, beautiful and tired, Djuna Barnes is talking about her novel Nightwood to T. S. Eliot.

Scott Fitzgerald likes to sit and read on the stoop in the sun, and Sylvia Beach has made up her mind to publish Ulysses, because no one else will.

Sylvia Beach in front of Shakespeare and Company on 8 Rue Dupuytren, Paris c. 1920 (Princeton University Library)

Sylvia Beach in front of Shakespeare and Company on 8 Rue Dupuytren, Paris c. 1920 (Princeton University Library)

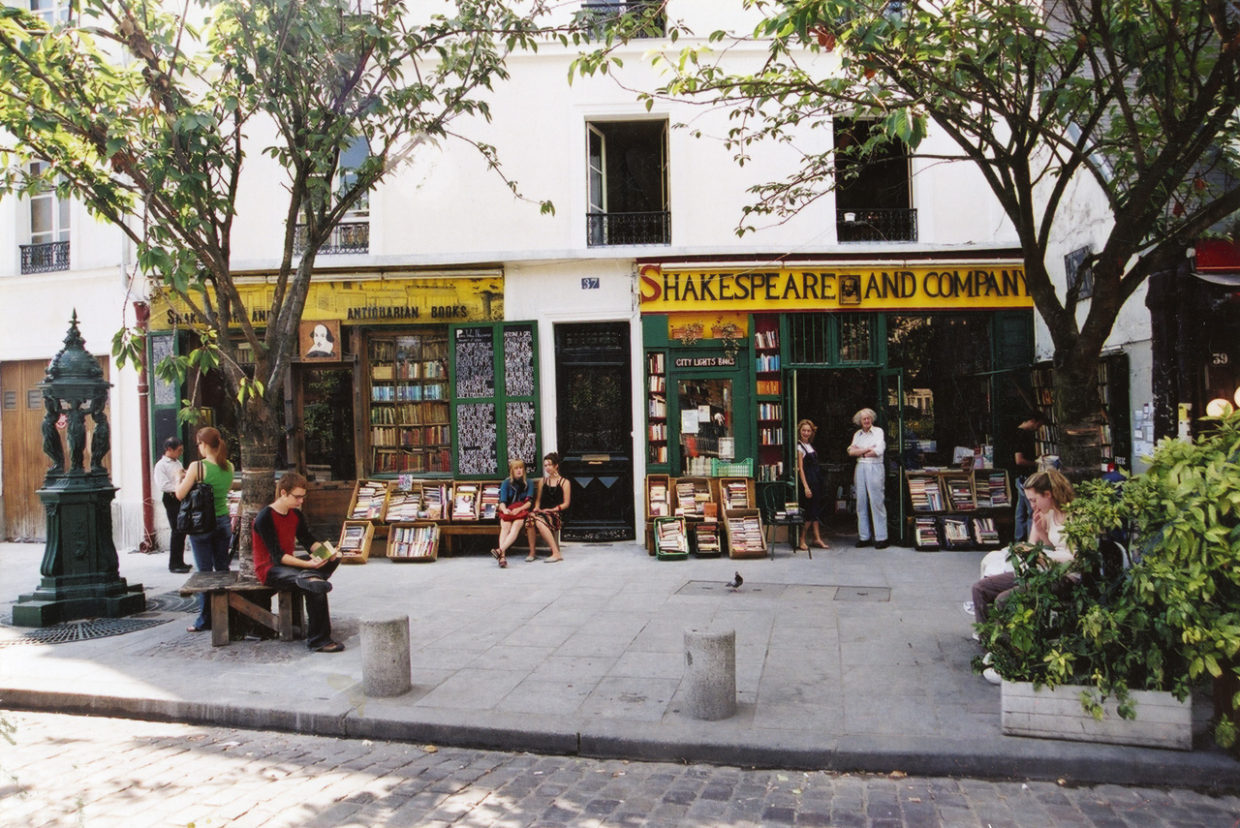

This is 3-D history. The past alive and well and time-traveled into the future. If you read somewhere that the book is dead, come to Paris. One hundred years later, Shakespeare and Company is busy like the book has just been invented and everyone wants one.

Young and old, rich and poor, writers and readers from around the world meet friends and make friends, come to browse the stock, buy the books, read all day in the library, get good coffee from the café, organize pop-up poetry slams, find a home from home.

(Tobias Stäbler)

(Tobias Stäbler)

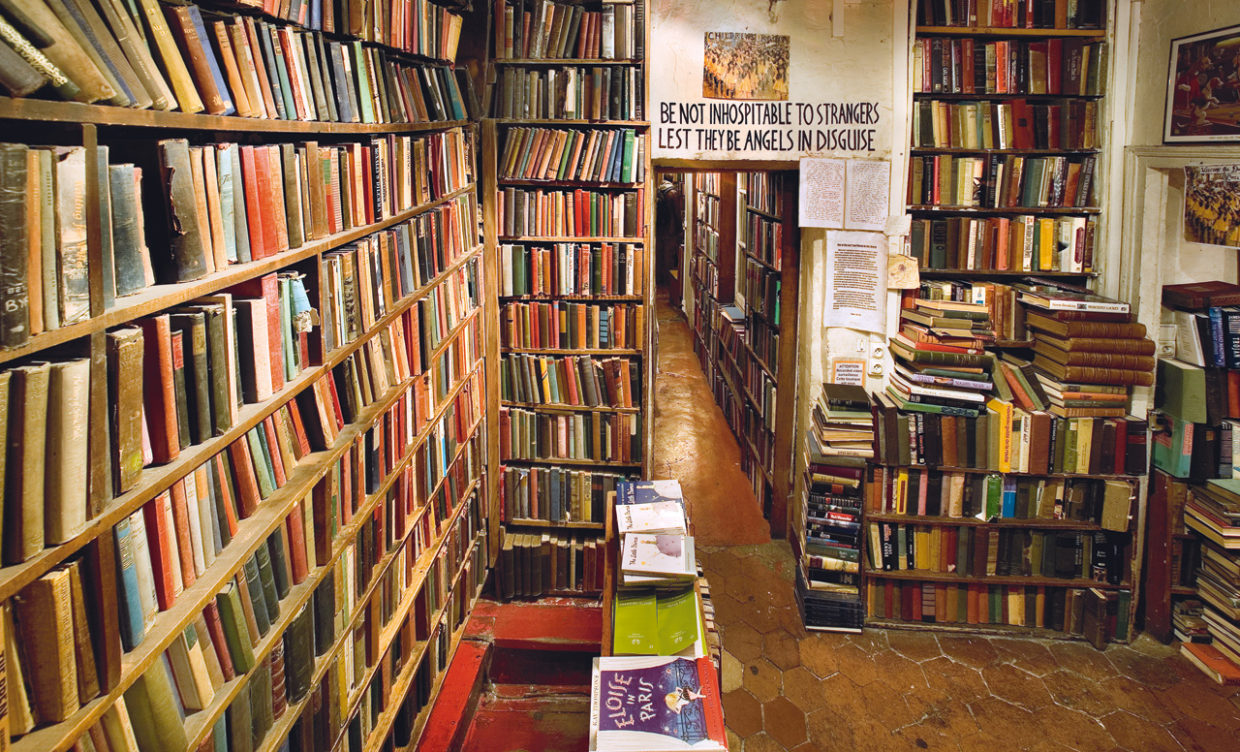

“Be not inhospitable to strangers,” says the sign, “lest they be angels in disguise.”

Go inside Shakespeare and Company today and you will see that sign written up as George Whitman left it.

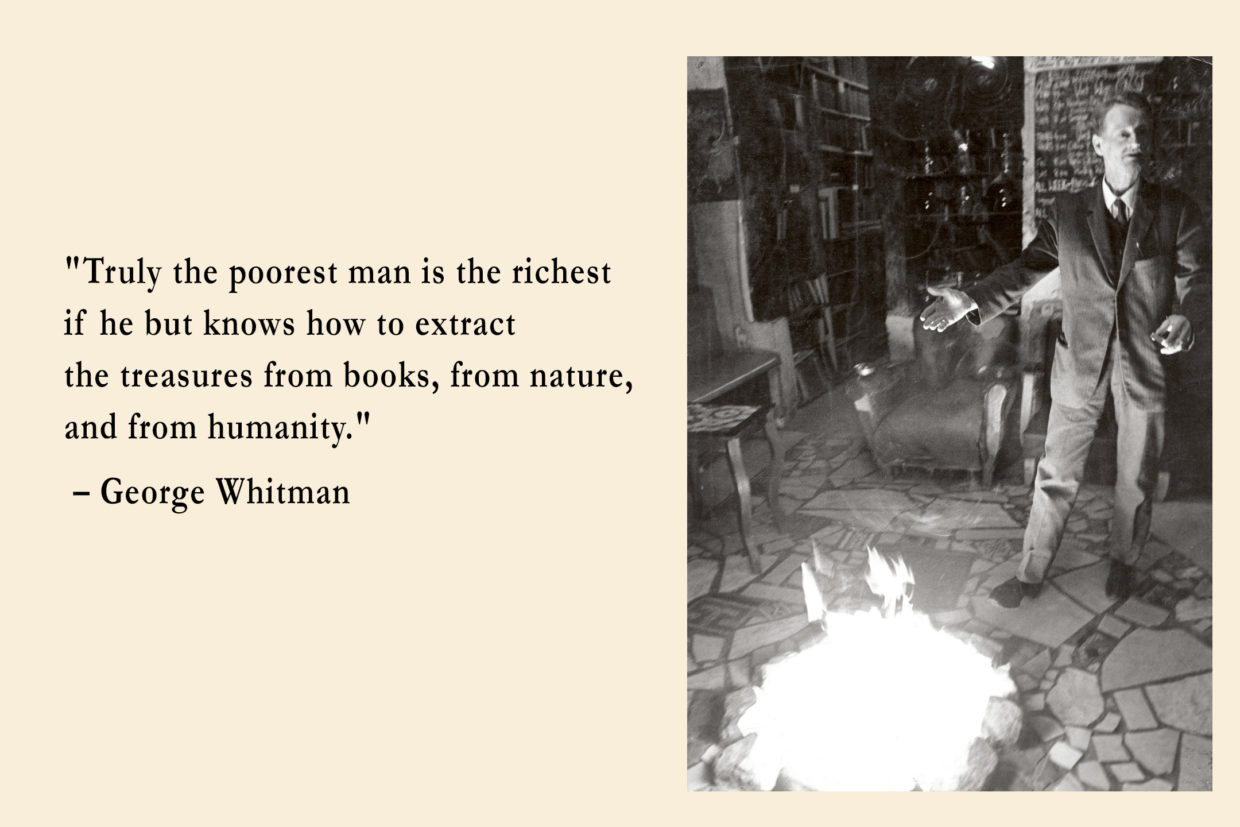

George attributed it to Yeats. In fact it’s the Bible, Hebrews 13:2. But George believed that all good books are bibles, in the sense of how to live, and in the sense of something transcendent, bigger than, or beyond, the here and now.

When George Whitman arrived in Paris soon after World War II, he knew all about Sylvia Beach and Shakespeare and Company—anyone interested in books knew all about it—but the shop had been forced to close in 1941. The Germans had occupied Paris and Sylvia Beach had been interned.

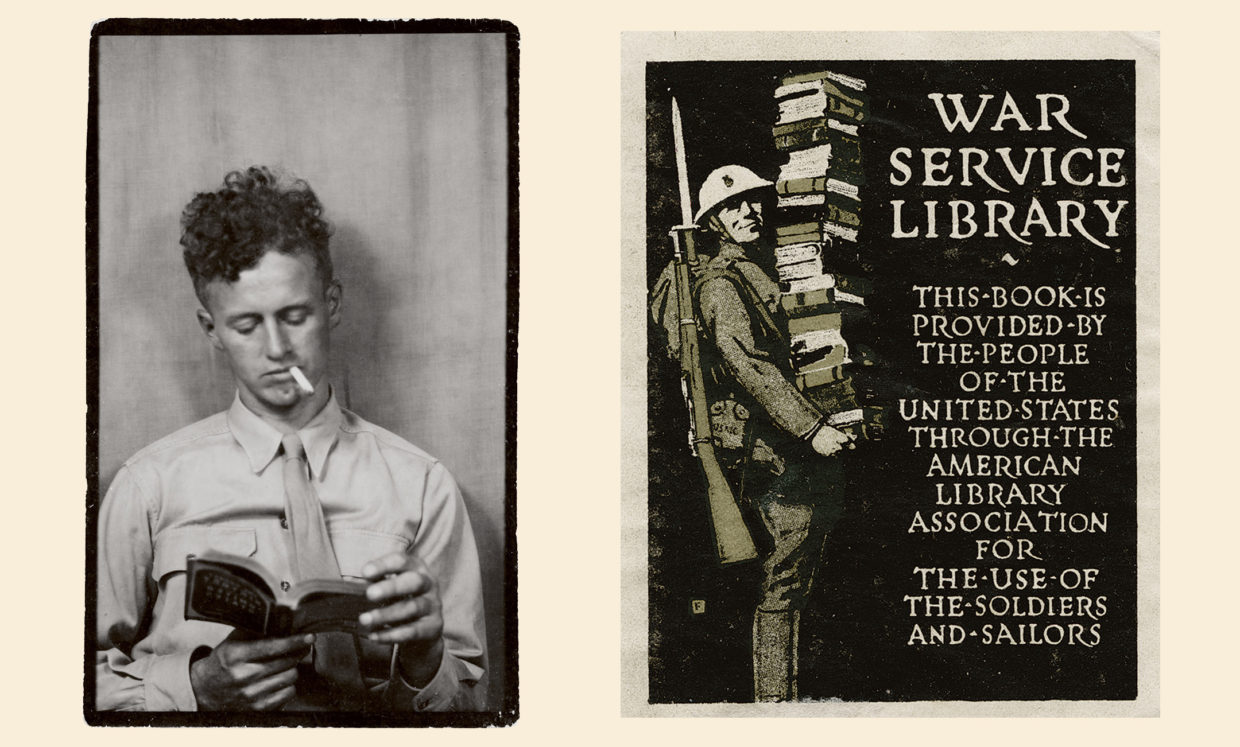

A photo-booth picture of George and a World War II bookplate found among George’s papers.

A photo-booth picture of George and a World War II bookplate found among George’s papers.

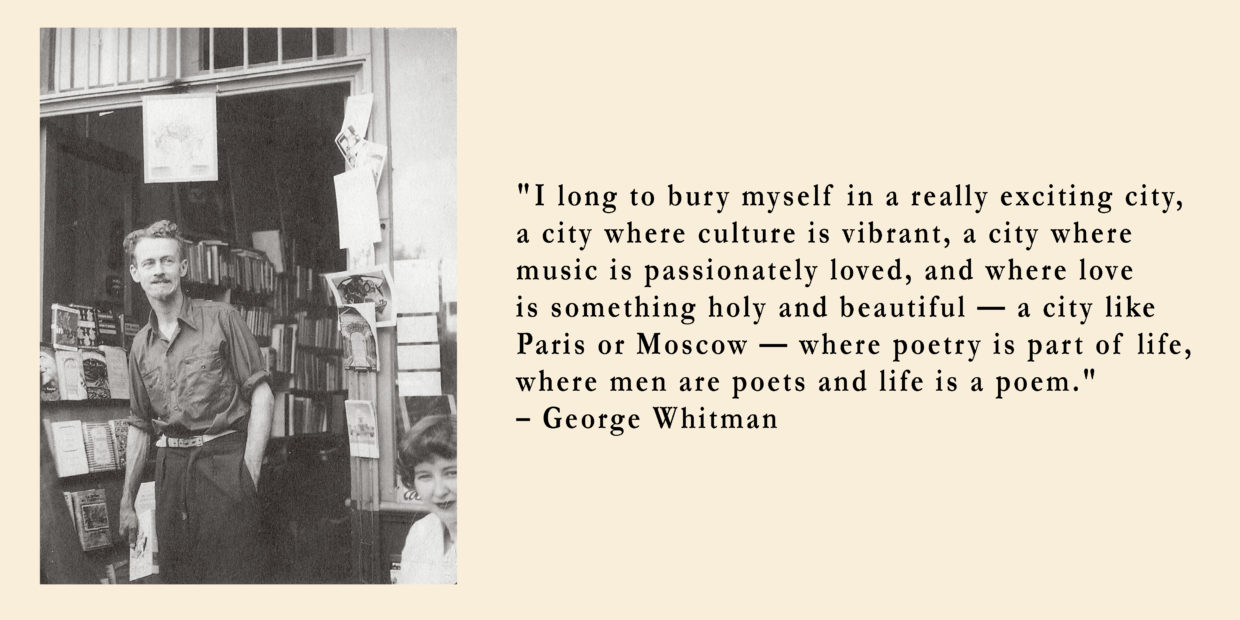

George fell in love with Paris, living in cheap hotels and collecting so many books that in 1951 he had to open a bookstore to find somewhere to put them.

That store, where it is now, 37 rue de la Bûcherie, kept up the spirit of the Shakespeare mother ship, inviting writers to eat, sleep, and work there.

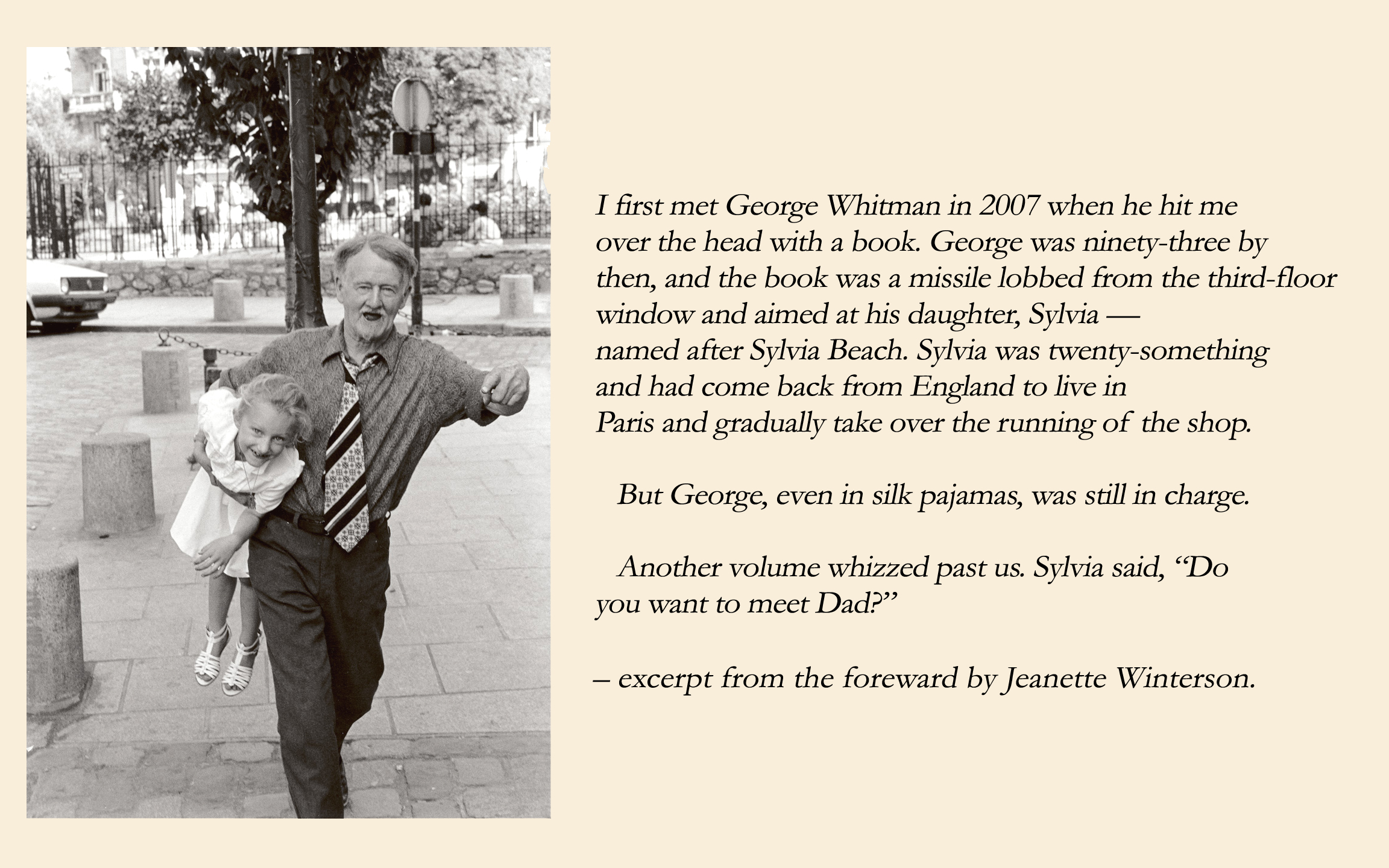

George was really operating as Son of Sylvia, as banker, sponsor, hotel keeper, publicist, evangelist for the new, defender of the known. So much so that when Sylvia Beach went along to a reading at the store in 1958, she gave a short speech and the famous name went up again. Shakespeare and Company was back in business.

George was really operating as Son of Sylvia, as banker, sponsor, hotel keeper, publicist, evangelist for the new, defender of the known. So much so that when Sylvia Beach went along to a reading at the store in 1958, she gave a short speech and the famous name went up again. Shakespeare and Company was back in business.

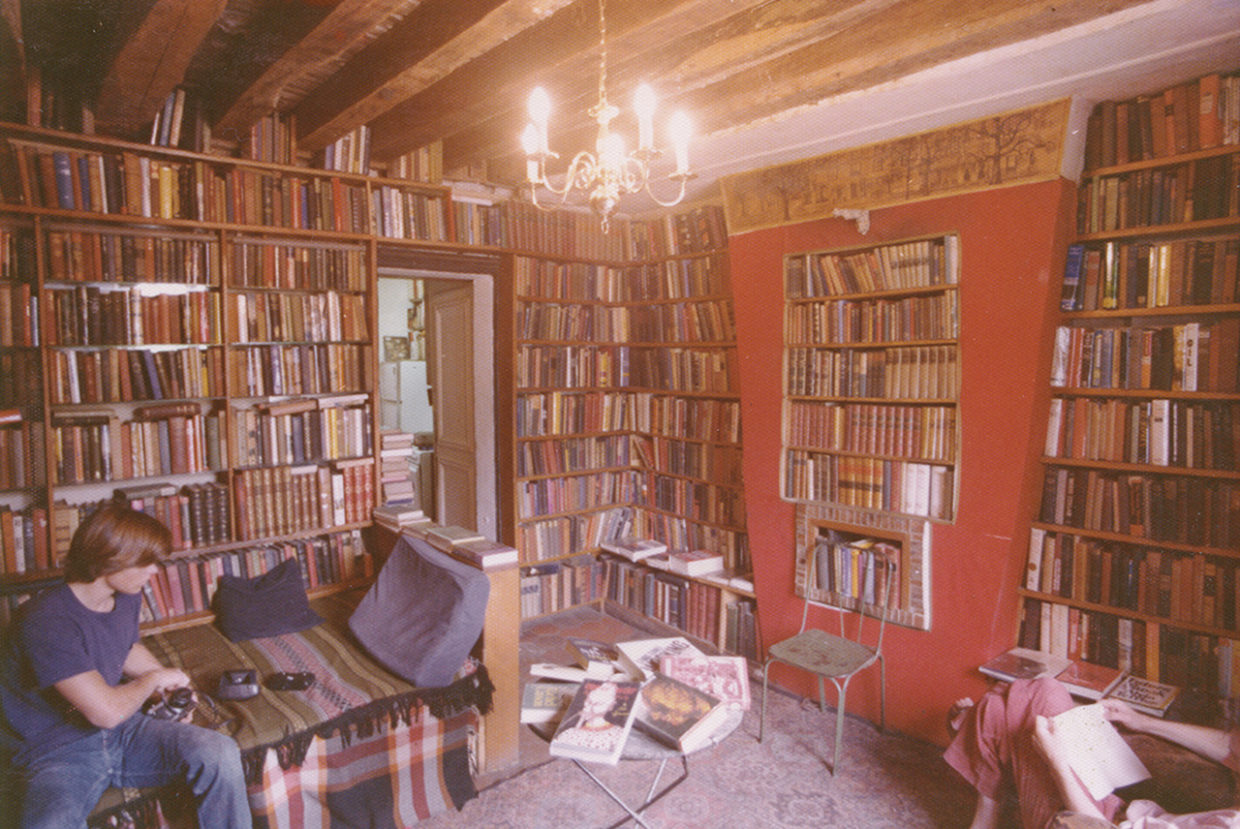

The shop is like a Tardis—modest enough on the outside, a labyrinth on the inside. Every vertical space is shelved with books of every kind. A rickety staircase carries you like a fairy-tale hero to a warren of rooms on the first floor where you will find treasure. There’s a piano, a typewriter in a booth, a few armchairs, a couple of cats, a big reading room looking out onto Notre-Dame. The bustle is the energetic kind of the life of the mind. It is uplifting to be here. It is an antidote to commercialism. Yes, this is a great business doing a good trade, but Shakespeare and Company is a reminder that business and pleasure can go together. As George put it, “the business of books is the business of life.”

–Jeanette Winterson

From the foreword to Shakespeare and Company Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart (Krista Halverson, ed.)

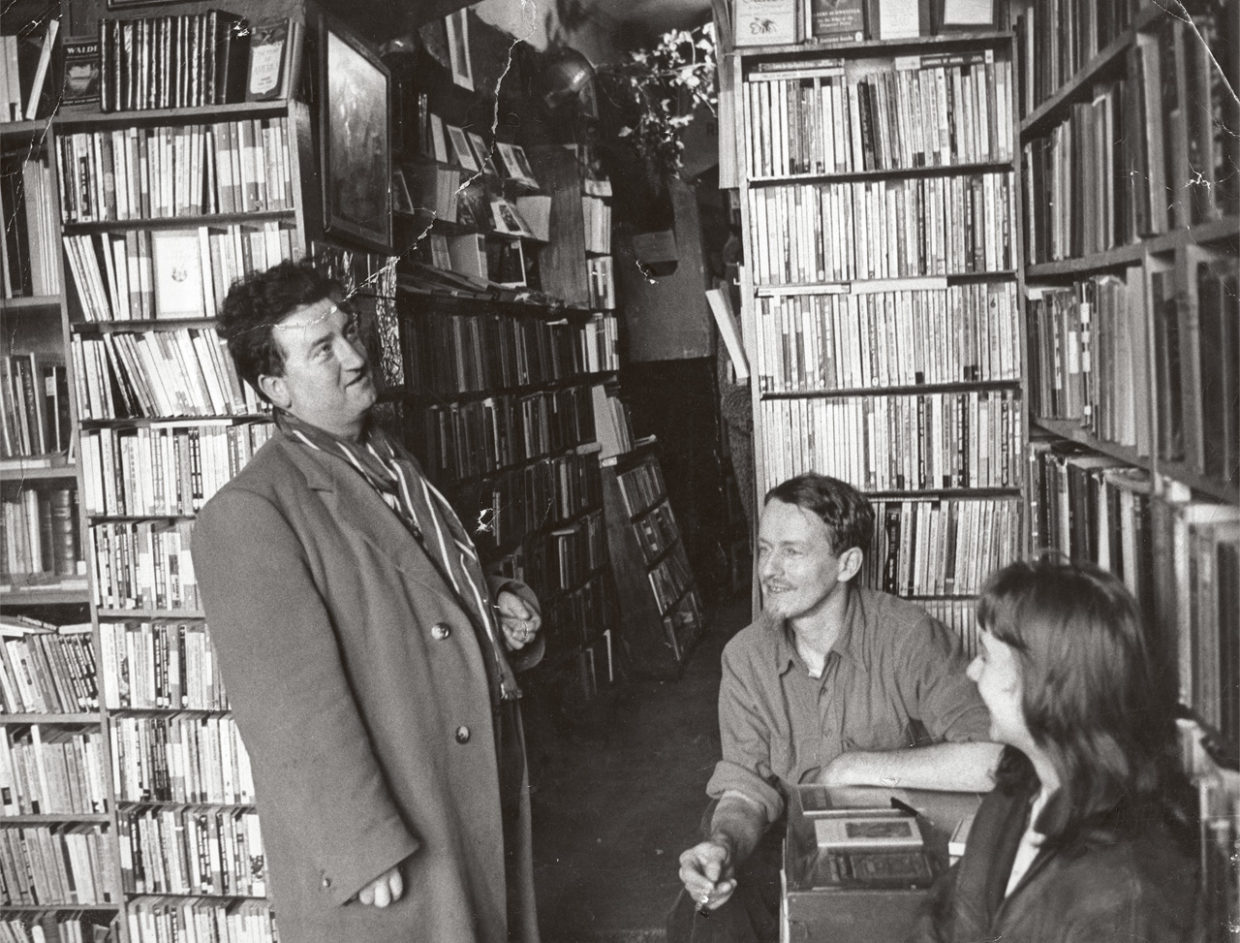

Brendan Behan with George and a friend.

Brendan Behan with George and a friend.

Richard Wright gathers with others in front of the shop. (Russell Melcher)

Richard Wright gathers with others in front of the shop. (Russell Melcher)

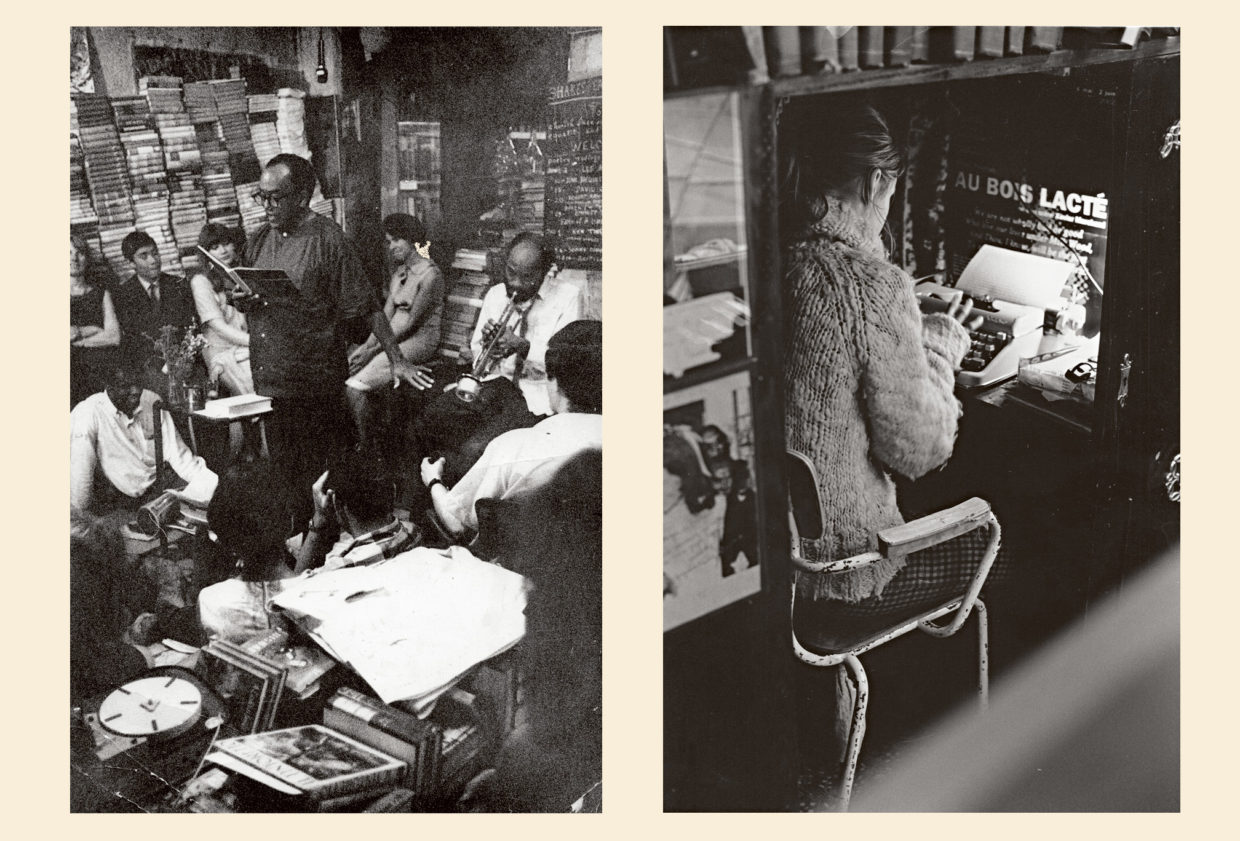

Langston Hughes reciting his poetry accompanied by Ted Joanes on trumpet. George is said to have built the writer’s nook when a Tumbleweed complained that there was no private place to write at the shop.

Langston Hughes reciting his poetry accompanied by Ted Joanes on trumpet. George is said to have built the writer’s nook when a Tumbleweed complained that there was no private place to write at the shop.

(Anne Nordmann)

(Anne Nordmann)

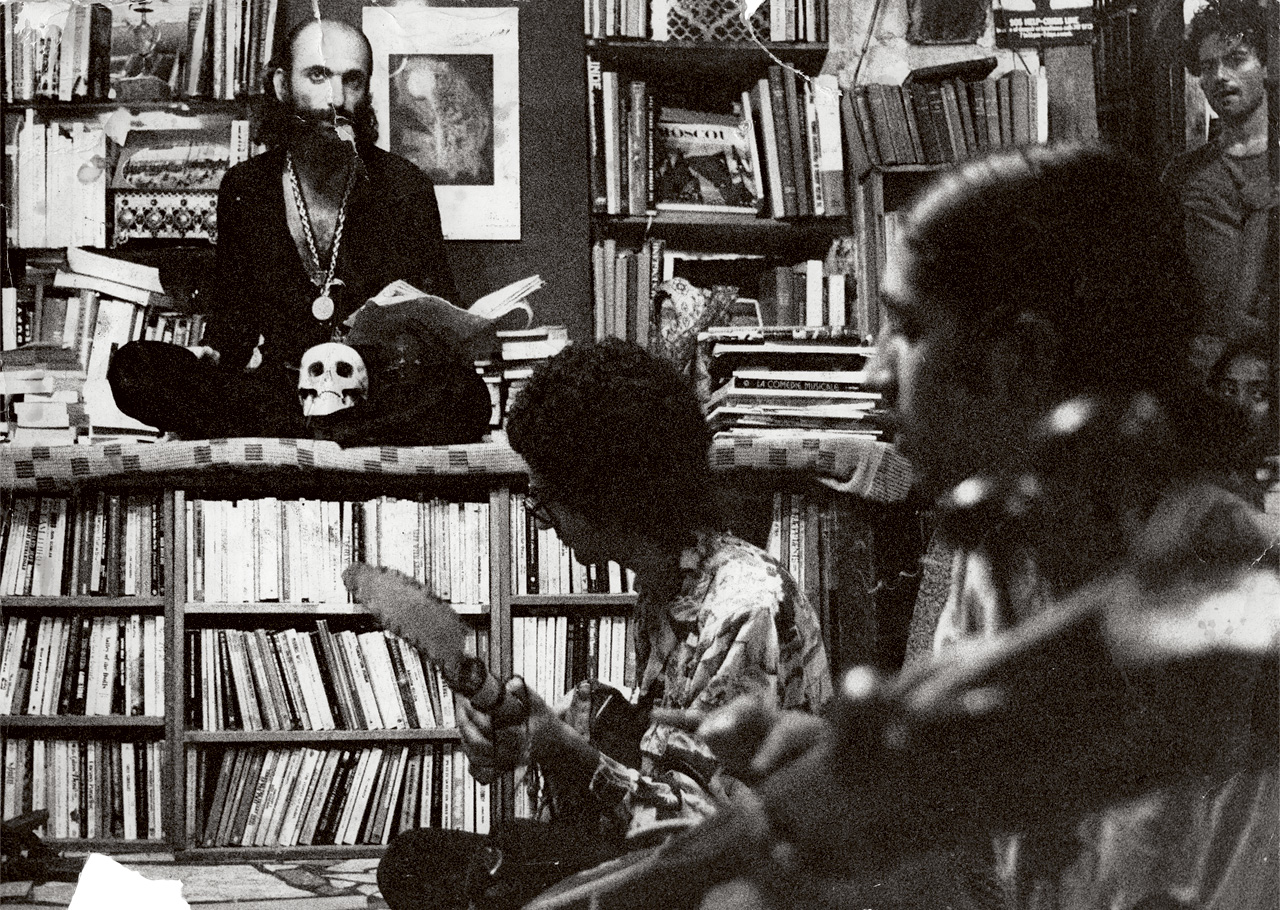

Writers are invited to sleep in the shop in exchange for helping out a few hours and writing a one-page biography for the bookstore’s archive. George called his guests “Tumbleweeds” after the dry, rootless plants that “drift in and out on the winds of chance.”

Writers are invited to sleep in the shop in exchange for helping out a few hours and writing a one-page biography for the bookstore’s archive. George called his guests “Tumbleweeds” after the dry, rootless plants that “drift in and out on the winds of chance.”

Sylvia and George in the doorway to the main bookshop. (Gillian Garnica) “When Sylvia took out one of the makeshift beds and installed a computer, George was furious. But father and daughter adored each other, too, and Sylvia is exactly whom Shakespeare and Company needs to carry it forward into the next hundred years.” –Jeanette Winterson

Sylvia and George in the doorway to the main bookshop. (Gillian Garnica) “When Sylvia took out one of the makeshift beds and installed a computer, George was furious. But father and daughter adored each other, too, and Sylvia is exactly whom Shakespeare and Company needs to carry it forward into the next hundred years.” –Jeanette Winterson

Sylvia and George. (Gillian Garnica)

Sylvia and George. (Gillian Garnica)

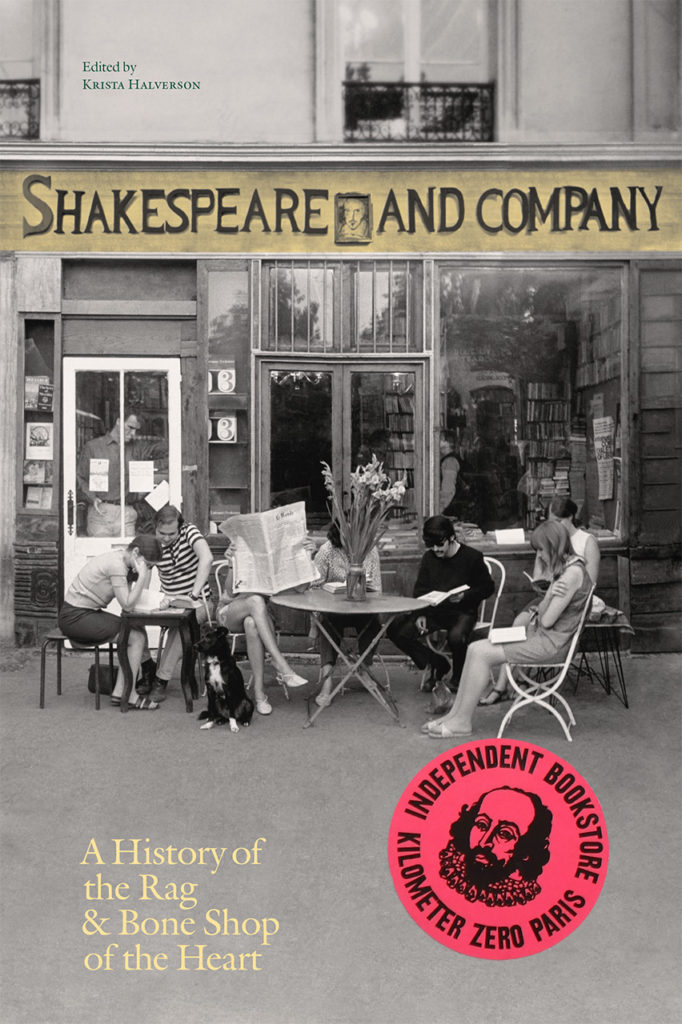

A History of the Rag & Bone Shop

of the Heart

Edited by Krista Halverson

© 2016 Shakespeare and Company Paris

Lit Hub Photography

Photography excerpts are curated by Catherine Talese and Rachel Cobb.