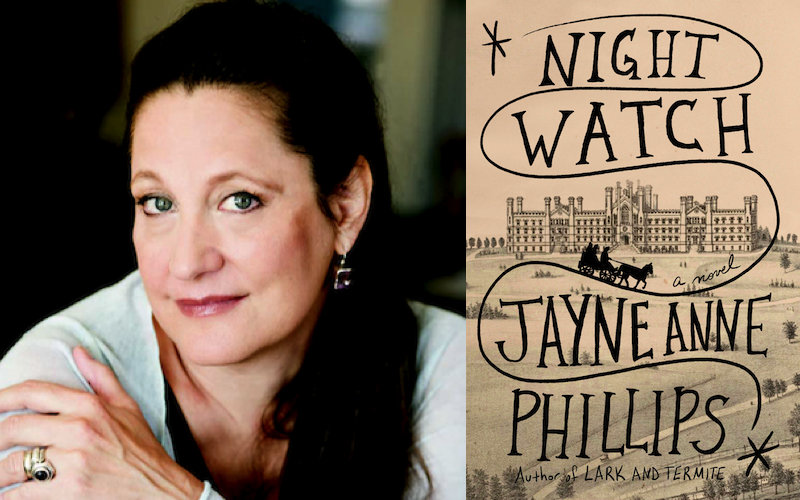

Jayne Anne Phillips on Uncovering the Hidden Aftermath of the Civil War

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Night Watch

Jayne Anne Phillips’ Night Watch is a dazzling and original masterpiece that evokes little-known aspects of the Civil War and its aftermath. The settings range from a sheltered ridge in the Appalachians to the Battle of the Wilderness to the West Virginia Lunatic Asylum that follows the teachings of a humane Quaker physician. The characters are idiosyncratic, consistent, vivid, and haunting. Phillips makes a case for this Civil War era as a prelude to our own turbulent times. “Night Watch is about the post-apocalyptic world of the Civil War years, the tribal divisions, the search for scarce resources, a specific family fallen apart and struggling to survive,” as she put it during our email conversation. “Now we seem to be living in a slowly unfolding apocalypse, climate emergencies everywhere, online-assisted conspiracy theology, ever-evolving viruses. It’s somehow reassuring to enter a turbulent (novelistic) past in which changed characters adapt, and stay in our minds. Time is a bellowing freight train, and it’s also the floating presence of all things, in all times.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have your life and work been going in the post-quarantine world? How have the years of pandemic and turmoil affected the writing, editing, and launch of your new novel, Night Watch?

Jayne Anne Phillips: The pandemic closed down the world, but it was mostly during those years that I began to understand the layering threads of the novel, and I wrote the ending. I felt as though the isolation and turmoil, the need for safety and refuge, were present inside Night Watch—the cyclical nature of history, the cycle of creation/decline, felt compassionate, comforting, mournful, yet hopeful. Science and technology in the 1860’s-70‘s included railroads and daguerreotypes, whereas today technology is seen as both savior (Covid vaccines) and devil (the pathogen that escapes the lab, bots that agitate political dysfunction, disinformation that undermines trust of legitimacy itself). Launch of my novel? More and more stacks up against the literary novel, the book of poetry…Feeling a true passion for literature is almost like membership in a medieval guild, a time when artist monks wrote out illumined texts and comprised most of their readership. Flashing forward, one can imagine, after the dystopian Long Pause or Full Stop—the cessation of the machine, the end of readily available electricity—forest dwellers and urban survivors breaking into structures looking for canned food and…books.

The Civil War, with its migrating populations, separated families, displacements and broken governments…casts a long shadow.

JC: What drew you to write about characters immersed in the Civil War and its aftermath in West Virginia, your home state, with a focus on brain injury, trauma from sexual abuse, and the healing theories of the Quaker physician Thomas Story Kirkbride, who created the philosophy behind the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum?

JAP: I grew up twenty minutes from what began, in 1858 Weston, Virginia, as the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum. It was the only appropriation Virginia ever supported in the mountainous western “frontier” of the state. Many educated Americans don’t know that West Virginia seceded from Virginia to fight for the Union. And the asylum itself, like most of the vast State asylums built in that era, followed guidelines laid out in Thomas Story Kirkbride’s 1854 book, On The Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane. Kirkbride emphasized “moral treatment,” strict regimens of physical exercise and activities, the asylum as healing refuge with gardens, barns, dairies; he demanded a strict maximum of 250 patients, each with a private, well-ventilated room. Trans-Allegheny, its wings extending a fourth of a mile, enclosed nine acres of interior space on nearly three hundred acres of farmed land and marked walking trails. Today the asylum, part ruin, part restored fantasy, is open to the public and remains one of the largest hand-cut sandstone buildings in the world, second only to the Kremlin. I visited several times and took some of the photographs that appear in Night Watch; other images are documents housed in State archives.

But my novels begin with the voice of a character involved in an ongoing, specific situation; I saw ConaLee and her mother, Eliza, on a journey to the room I photographed in the “restored” asylum. War is trauma. Abuse of “civilians” and sexual assault of women is common, even weaponized, in every war, then and now. Soldiers maimed for life in the 1860’s remained devastated. Imagine, in an American population of roughly 30 million, 1.5 million dead, wounded or captured (according to the Battlefield Trust). Numberless widows and orphans. Night Watch invites the reader to survive that devastation in the experience of one family, already rendered nameless, fleeing one hard won refuge for another, and another…

JC: What inspired your title, Night Watch, and the character known as Night Watch, and John O’Shea, among other identities?

JAP: There are always those nameless, forgotten individuals who are moral fulcrums no matter what threat or loss they suffer. Dearbhla is such a character, and refers to her adopted son as “her one.” He’s known as “Sharpshooter” during the war, and later “lent” the name, John O’Shea. His identity shifts as he inhabits one ‘life’ after another. “Night Watch” is a position at the asylum, and namelessness is a theme in the novel. Even before the War, ConaLee, Eliza, Dearbhla, and her adopted son, keep their family name secret for reasons that unspool in the novel. Think of Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch,” that massive, moody portrait of guardsmen charged with defending their cities. Night Watch is a moral and physical necessity, comprised within one man in the novel—a man secret even to himself—whose nature it is to protect, defend, survive, thrive, if given the chance.

JC: You begin Night Watch in 1874, as a mute mother and her daughter, who pretends to be her servant, arrive at the asylum in Weston, Virginia, and are welcomed by Night Watch and Mrs. Bowman. What research did you do to be able to re-create this asylum for 250 women and men with multiple activities, its chief physician, Dr. Thomas Story, and complex staff, including the Hospital Cook, Mrs. Hexum, with her staff and the group of children she nurtures?

JAP: The novel starts in 1874, nine years after the war, inside the immediacy of ConaLee’s voice. A twelve-year-old girl, the adult in her family for as long as she can remember, she undertakes a journey with her mute mother and the man she’s been told to call “Papa.” And so our story begins, while the novel, after we “know” the characters, moves back to 1864, amidst the War, to reveal what made and changed them, though revelations continue throughout the novel. Research included Kirkbride’s book and books about him, my own preoccupation with the irony of “moral treatment” within such a brutal, tortured era, and, well, shelves of books about the War and the times: Ken Burn’s PBS series, “The Civil War;” The Civil War Told By Those Who Lived It, four volumes of diaries, military accounts, letters, published by Library of America; Rankin Sherling’s The Invisible Irish, Keri Leigh Merritt’s Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South and numerous books on herbal medicine and medical practices of the time. Realizing the enormity of national trauma and the myth of “the good death” as characterized in Drew Gilpin Faust’s The Republic of Suffering: Death in the American Civil War, was key.

JC: You include illustrations—maps, photographs, drawings. How did you choose them?

JAP: There were originally many more illustrations, but those that remain are intrinsically connected to the narrative: the ladies’ magazine page, referred to as “thee and thine” in the novel; historical photographs of the asylum that comprise spaces the characters actually know. All are meant to. History tells us the facts, but literature tells us the story, and these images help underscore the reality behind the story. Night Watch almost begins with “You’ll tell the story,” a phrase tossed off to ConaLee as she’s left behind. Without story, we don’t truly penetrate history.

JC: Your characters Eliza, and her daughter ConaLee, the daughter of the sharpshooter, are at the heart of the novel. In 1864, Eliza knows about “woodcraft, home craft, trapping, hunting.” She and Dearbhla “used woods medicine, cooked, grew vegetables in sunny patches of ground.” I’m curious about the archival information about such homesteading in those mountains, and how you were able to detail the herbs, animals, garden produce used in these times?

JAP: Herbal remedies were the only medicine for most, and babies were born at home, in whatever served as home. I loved entering this world unspoiled by industry, in which nature dominated, when it was possible to survive in the mountains, devoting all one’s time to daily provisions and preparing stores for the next season. Living “off the grid” was hard, grinding work nearly two hundred years ago, when the grid itself was so limited; the resourceful and fortunate succeeded. Years of continual research, including films, books of photographs and Appalachian folklore, accounts of the past, family stories, and familiarity with real places still reminiscent of the wild, like New River Gorge and the “hills beyond hills” I saw from my childhood home.

I’m fascinated by consciousness itself, by simultaneous time as reflected in the floating mind, the blinkered mind.

JC: In 1874 Eliza, now known as Miss Janet, is mute, admitted to the asylum. How were you able to render her trauma so powerfully through the flashback scenes leading up to the asylum days?

JAP: I was living inside her, I suppose. And Dearbhla and ConaLee were witnesses to pieces of her experience.

JC: The vision of Dearbhla, descended from Protestant Irish indentured servants, infuses the novel’s narrative throughout. Is she based on a real character? Or immigrant group?

JAP: Dearbhla is not based on a real character, but on what is known about poor Irish whites, illiterate for generations, who migrated with nothing and served long terms as indentured manual labor. The Irish in the South, particularly, were judged by the rampant alcoholism of the men, who could not find work in economies based on slavery, many of whom gave up, leaving their women and children to lives of bitter poverty.

JC: You describe the sharpshooter’s brain injury, the battlefield hospital where he recovers, his treatment, his gradual return to awareness and ultimate state, in great detail. What was the process of writing these scenes like? How much did medical professionals know about brain injuries at that time?

JAP: I’m fascinated by consciousness itself, by simultaneous time as reflected in the floating mind, the blinkered mind. Medical doctors knew very little about the brain then, or they subscribed to myths about “humors.” The Civil War hospitals in Alexandria, a city given over to the treatment of the wounded, were probably among the most enlightened of the day. “Old” Dr. O’Shea and his assisting nurse, Mrs. Gordon, are two more of the mostly unsung heroes in Night Watch. Their close attention, their common sense, their encouragement of the injured to help one another, their recognition of their patient’s innate abilities despite his maimed appearance and diminished faculties, are still at the heart of what healing humanity can manage.

JC: Are you visualizing the country’s current state of division as resembling this time in American history?

JAP: Absolutely. The Civil War, with its migrating populations, separated families, displacements and broken governments, entrenched points of view that lead to heartbreak and breakdown, casts a long shadow, and that shadow emerges more and more starkly. I see Night Watch as the third of a trilogy of war novels, beginning with Machine Dreams (the Vietnam war as experienced by one American family) and moving through Lark And Termite, which imagines a real event in the Korean War and its generational impact on two motherless children. In a sense, we are all those children. Statistics vary, but the Union that survived the War saw 4,743 lose their lives to lynching between 1882 and 1968 (NAACP). The Tuskegee Institute puts that number at 3,446, of whom 72% were Black, and 1,297 were white “provocateurs,” or those seen to be aiding Blacks. Entrenched institutional attitudes still reflect Civil War tropes. Foreign entities, effectively undermining what was once referred to as Western Civilization, actively support division and domestic terrorism.

A soldier character in Lark And Termite believes “It’s all one war,” implying that locations, weapons, ideologies, change, but the same fires flare up.

Yet the timeless nuances of human identity pull in an opposite direction, the direction of whoever and whatever stands as night watch, acting to protect and sustain despite chaos, to gather up, to survive to a time when all of us can finally say our names.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

JAP: I’m working on a collection “about writers and writing” that includes memoir and addresses the very recent lost past, and the idea of origins in a world obsessed with origin stories.

__________________________________

Night Watch by Jayne Anne Phillips is available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.