James Baldwin’s Children’s Book Will Help You See the World with Fresh Eyes

On Reissuing the Quietly Radical Little Man, Little Man

2017 was a watershed year for the legacy of James Baldwin. I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary. Barry Jenkins, director of the Oscar-winning feature, Moonlight, announced that his next film will be an adaptation of Baldwin’s 1973 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk. On the front page of the New York Times came the news that the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture acquired a massive archive of Baldwin’s papers, now available for public view. Baldwin’s prophetic words on race relations continue to be quoted and engaged in national and international conversations about race with renewed force and urgency in the era of Black Lives Matter.

It is against this backdrop that a forgotten Baldwin book, entitled Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood, is being republished by Duke University Press today after more than 40 years of obscurity. Originally published in 1976 by Dial Press in the United States and Michael Joseph in London, the book’s formal innovation and subject matter—the lives of black children in Harlem—didn’t resonate with readers at the time, and it went quickly out-of-print, despite the fact that it was profoundly important to Baldwin, who called it a “celebration of the self-esteem of black children.”

I discovered this book over 20 years ago at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library when I was an undergraduate at Yale in search of a subject for a senior thesis. I was immediately struck by just how much it was unlike anything else Baldwin had written. Or unlike anything anyone had written, for that matter. Its cover image of a black boy wearing a blue beret as he plays ball in front of a Harlem apartment building, along with the book’s large type-size and abundance of colorful illustrations, give it the look and feel of a children’s book. But right away the inside jacket flap’s blurb and its accompanying author images let me know that I was in for a surprise.

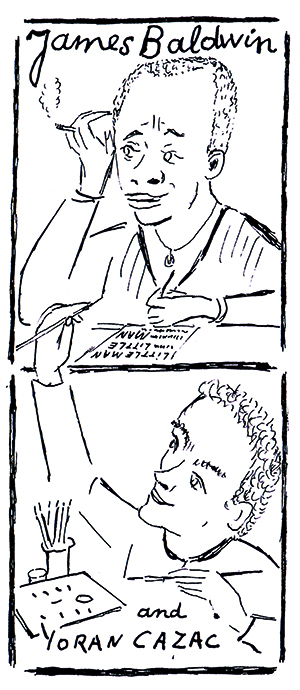

Little Man Little Man is a child’s story for adults. In a few words, James Baldwin has created a microcosm of his concern for our children and our future. Because the characters are children, the story dances along with a child’s rhythm and resilience, making an unforgettable picture of New York as it looks to those who are black, poor, and less than four feet high. It is dramatically illustrated by Yoran Cazac.

In the image the book’s illustrator seemed to be painting Baldwin writing—a playful collaboration. Baldwin was even smoking a cigarette. But what did it mean that it was called a “child’s story for adults”?

Illustration by Yoran Cazac.

Illustration by Yoran Cazac.

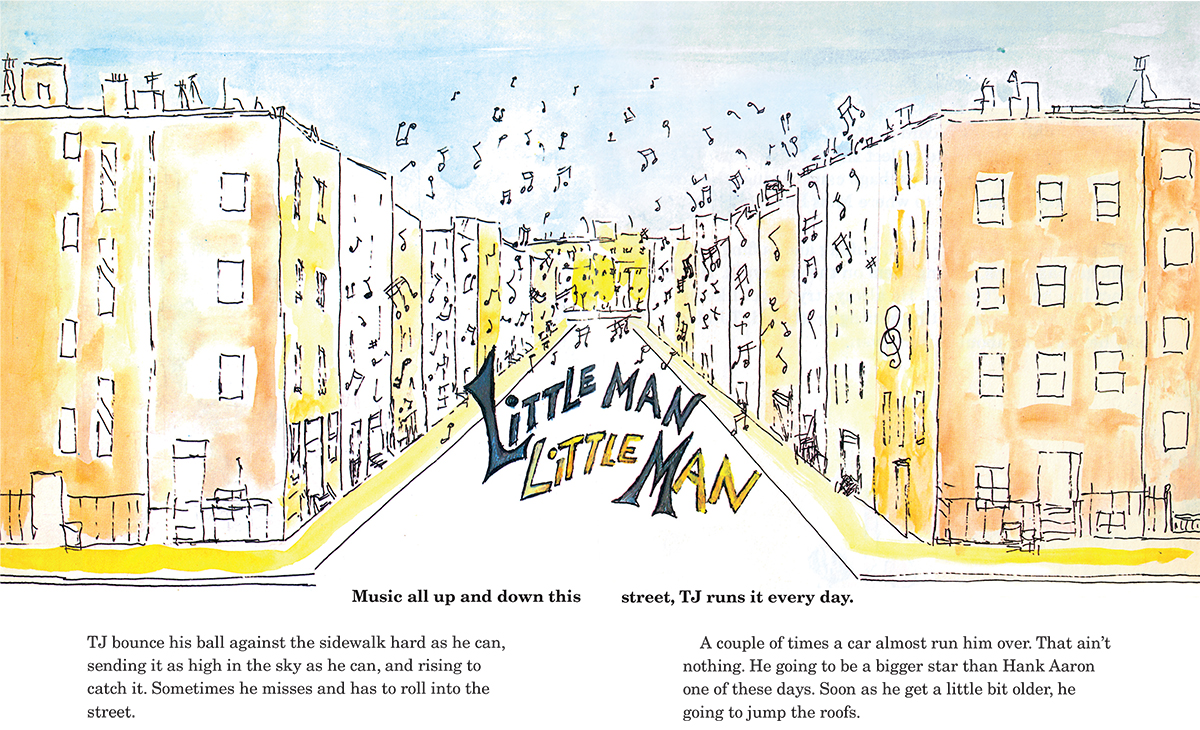

My sense of wonder only deepened as I began to read the book. The first two pages depict a broad empty Harlem street lined by old apartment buildings with sketchily-drawn music notes floating in the blue sky above.

Text by James Baldwin, Illustration by Yoran Cazac. Click to Enlarge.

Text by James Baldwin, Illustration by Yoran Cazac. Click to Enlarge.

Narrated by a child-like voice in the vernacular black English of Baldwin’s youth, the book’s perspective roams freely as it tells the story of three children—two black boys, four-year-old TJ and seven-year-old WT, and an eight-year-old black girl named Blinky—as they navigate the pleasures and dangers of their Harlem neighborhood. There is something inexplicable about the book. No, actually, almost everything is inexplicable about it. Random fragments of text are highlighted in bold, for no apparent reason. It tackles complex themes like drug addiction, alcoholism, police brutality, and the racist distortions of the mass media. It’s a children’s book but it’s also not a children’s book. It’s beautiful and messy and it was, to be sure, unlike any book I’d ever seen.

“I was immediately struck by just how much it was unlike anything else Baldwin had written. Or unlike anything anyone had written, for that matter.”

And yet it is still quintessential Baldwin. In his essay, “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me What Is?,” Baldwin wrote that “the bulk of white people in America never had any interest in educating black people, except as it could serve white interests,” laying the groundwork for his argument about the necessity of affirming what his friend Toni Morrison called the “sheer intelligence” of black English:

It is not the black child’s language that is despised. It is his experience. A child cannot be taught by anyone who despises him, and a child cannot afford to be fooled. A child cannot be taught by anyone whose demand, essentially, is that the child repudiate his experience, and all that gives him sustenance, and enter a limbo in which he will no longer be black, and which he knows he can never become white. Black people have lost too many children that way.

Baldwin’s assertion that language is “is a political instrument, means and proof of power…and the most vivid and crucial key to identity” helps explain how the vernacular voice in Little Man, Little Man resists both standard English and its cultural messages to imagine a different story of black childhood than any that came before or after it.

*

To find out more about the genesis of the mysterious book I tracked down Baldwin’s collaborator, the white French artist Yoran Cazac. In 2003 I conducted a series of interviews with him in his Montmartre studio in Paris. He told me that he met Baldwin in Paris back in 1959, introduced by their mutual friend, the black painter Beauford Delaney. The two men fell out of touch as their lives took them in and out of France, but they reconnected in Paris in 1971. Baldwin had recently made a trip from his adopted home in the south of France to see his family in New York. His nephew Tejan had long been imploring his famous uncle to write a book about him. Baldwin decided that now was the time.

Cazac had never seen Harlem, or even visited the United States for that matter, but Baldwin felt this lack of knowledge would actually help Cazac to visualize Harlem with fresh eyes, so he asked him if he would illustrate the book. Still, he knew he would have to educate Cazac about African American culture and his family in Harlem, in particular, so he could bring the book to life visually. He gave him a copy of The Black Book (1974), a groundbreaking compilation of words and images drawn from African American history. He also shared photographs of Harlem and of his family as models for his characters, including Tejan (TJ in the book). These sources along with Baldwin’s oral descriptions of the neighborhood allowed Cazac to capture a Harlem he had never seen or experienced in person. He completed a full draft of the images in crayon, but then he realized he wanted to work with pencil and watercolor instead, better, as he put it, to “imagine the unimaginable.”

“In the end, Little Man, Little Man gives all readers a way of viewing the world as they are not usually encouraged to see it.”

The final illustrations employ sketchy lines and bleeding colors from the faces of neighbors sitting on their stoops to the streetscapes of Lenox Avenue, creating a backdrop that both is and is not Harlem. Or, more precisely, it is a Harlem distorted into something at once familiar and strange, an unexpectedly beautiful mirror of Baldwin’s vision of the lives and landscapes of urban black children.

*

As the children move through Harlem together, playing ball, skipping rope, and running errands for neighbors, the character Blinky, with her “blinking” eyeglasses, increasingly acts as a surrogate older sister figure for the younger boys. At first TJ is skeptical of her eyeglasses since he can’t see out of them himself and some “white folks at school” bought them for her. But several pages later TJ is already learning that Blinky’s “own skin color” is changing all the time. She always makes TJ think of the color of sunlight when his eyes are closed and the sun is inside his eyes. When his eyes are open, she is the color of “real black coffee, early in the morning.” Just as Cazac explained his use of color and light in the book as featuring characters whose faces sometimes appear only partially painted: “In the full light, no one is fully black or fully white.”

Blinky. Illustration by Yoran Cazac.

Blinky. Illustration by Yoran Cazac.

In the end, Little Man, Little Man gives all readers a way of viewing the world as they are not usually encouraged to see it, in a rearranged angle of vision that allows for the intervention of refracted messages, aimed at a child’s understanding even if ostensibly written for an “adult audience.” The book is indeed a “child’s story for adults” because it encourages readers to don Blinky’s eyeglasses and see through the child’s eyes—in watercolor, as if everything has been rained on, as the critic Margo Natalie Crawford has suggested. As such, readers see the world from the vantage point of someone who is “black, poor, and less than four feet high.”

There is something quite radical about this, and also something very Baldwin. As LeVar Burton recently said of the new edition of the book, “Neither the native idioms of speech nor the world as seen through TJ’s eyes are meant by Baldwin to engender a sense of comfort in the reader. Instead he insists that we ‘come to correct’ and open ourselves to an experience of seeing the world anew through the eyes of another. Which of course is not only the basis of compassion, but classic Baldwin as well.”

Nicholas Boggs

Nicholas Boggs is co-editor and author of the Introduction to Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood by James Baldwin with illustrations by Yoran Cazac. His writing has also been anthologized in The Cambridge Companion to James Baldwin and James Baldwin Now. A Fall 2018 Fellow at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France, he is currently writing a book about love and race in Baldwin’s life and work. He teaches in the Department of English at New York University.