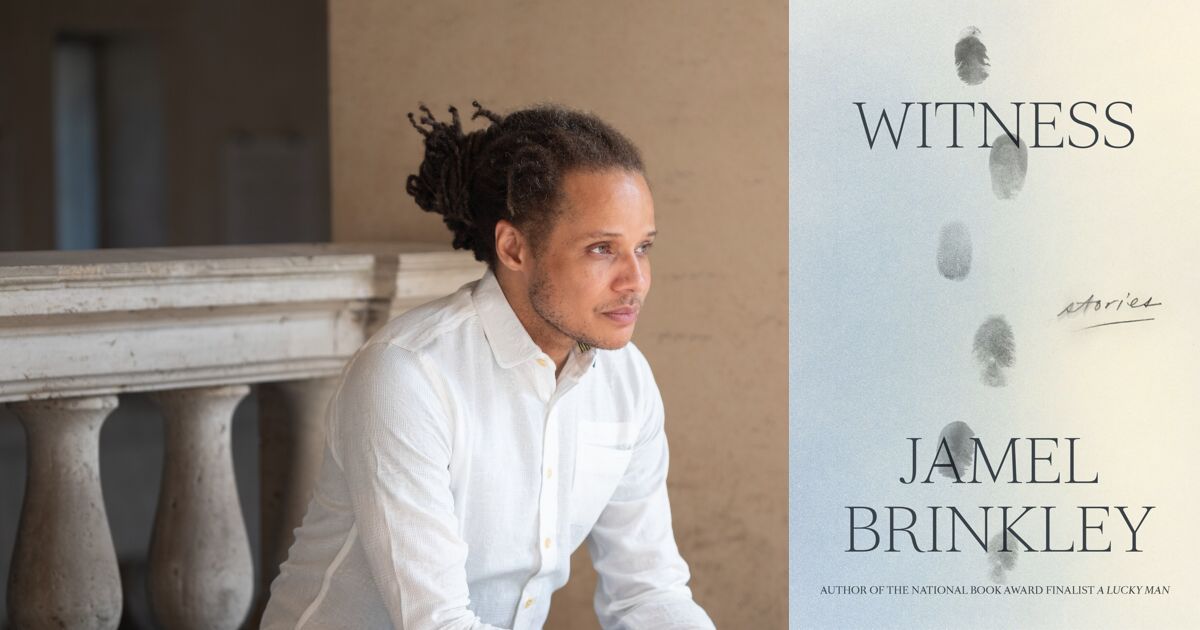

Jamel Brinkley on the Little Pleasures of Language

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

This week on The Maris Review, Jamel Brinkley joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Witness, out now from FSG.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

Maris Kreizman: I’m wondering if you could talk a little broadly about the variety of points of view you write from in this work, both from different people of different backgrounds, but also, POV.

Jamel Brinkley: Well, the first thing I’ll say is that, with A Lucky Man, for a number of reasons, I think because of the book itself (obviously the stories were focused on black men but also the timing of the book’s publication) I think that the narrative that quickly solidified around the book was that this is a book about masculinity or black masculinity, or toxic masculinity or what have you. And I think there’s a part of maybe any artist where you start to chafe against being boxed in like that. And I don’t think people meant it in any sort of way, but there’s a way in which I could do more than that, or I’m not just that.

And I do think that A Lucky Man covers more than just that topic. But with this book, I think I very intentionally wanted to write stories that sort of pushed out of that. So I do have point of view characters who are women or young women, old women, little girls. And yeah, it was also fun for me to write from a variety of POVs, different kinds of first person, where the first person is sort of muted or hidden for a while and then it starts to emerge. I think I had a lot of fun with that. Just seeing what’s possible within each of those POV choices, you know, to experiment within the first person, for instance, was a lot of fun for me.

MK: I think that that really comes across in the collection. And now I’m gonna ask you a very hack question that I know you can’t quite answer which is, I’m gonna say that the language in this book is incredibly striking. I’m not gonna just sit back and say like, how’d you do that? But I know you teach, so I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about prose and polishing and making unexpected word choices.

JB: I think a story becomes dynamic when there are things within the story that aren’t subservient to the plot. They can happen on a lot of levels. Sometimes they can happen on a level of say, dialogue. Some of our best dialogue writers are people whose just the things that the characters say are so out there, but out there in a pleasurable way, in a way that you accept, and it feels like it kind of opens up the world of the story a little bit more. It doesn’t feel like it’s on the track to its destination so strictly.

And so when you’re talking about language, I think language is another way where if you tune the sentences in a certain way you… The way you decide to work with a syntax, just the sentences themselves, can be these little pleasures that make you see more than just, this is where this story is going. You’re experiencing the story in this multisensory way. Like, the story’s coming at you from many directions.

*

MK: I’m wondering if you could talk a little bit about the order in which the short stories appear. The title story is the final one. I’m always fascinated by this. Was it your choice? Was it an editor’s choice? All of that.

JB: Yeah, it’s kind of a negotiation, I found, with both of these collections so far. I will say that, generally speaking, the sort of pillars of the collection were in place kind of from the beginning. So it makes sense for “Blessed Deliverance” to be the first story for a number of reasons because of the voice for instance, you know, that first sentence kind of jumps.

MK: Yes, it sure does.

JB: I hope it does. And then I think, you know, there’s, there’s something about. I co-taught a class with my colleague Margot Livesey this past spring on short story collections. And one of the things that we and the class thought about was sequence.

And it was really fun and interesting to read different writers talking about sequence. One of the things that I became fascinated with was the idea of notes. You know, like people will say, I want to end on this note, right? Which, when you hear it, you kind of understand it on the surface level, but when you think about it in terms of music, then it becomes really interesting.

So what is the sound journey that your collection is taking? And how do each of those sounds convey different kinds of emotions? For me, I think the journey from that first story to that last story is a journey from someone who… In some ways the narrators are similar kinds of characters in certain kinds of ways, meaning they sort of embrace inaction for different reasons.

But that first narrator really wants to be hidden, and that’s what the point of view choice kind of reflects. And then finally we have this character who emerges at the end of the story. And I think by the time you get to the end of the collection, there’s no way you can’t stare at that narrator, right from the beginning. You know, he’s so visible, even in his inaction and his neglect and his guilt.

*

Recommended Reading:

Lost in the City by Edward P. Jones • All Aunt Hagar’s Children by Edward P. Jones • The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard • Hue and Cry by James Alan McPherson

__________________________________

Jamel Brinkley is the author of A Lucky Man: Stories, which won the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence and was a finalist for the National Book Award, the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction, the Story Prize, the John Leonard Prize, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. He was raised in the Bronx and in Brooklyn, New York, and currently teaches at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His new story collection is called Witness.