Jack Torrance and Me: On Writing and Self-Loathing in The Shining

Maggie Su: "Just as part of Jack will always remain at the Overlook, my shadow is still part of me."

Jack Torrance is an emerging writer who’s just landed a sweet gig. In exchange for doing some routine maintenance on the historic Overlook Hotel over the winter months, Jack, his wife Wendy, and their son Danny, get a salary, free room and board, and what every writer covets: time to write. It’s a family-friendly multi-month writer’s residency that might attract 500+ applications in Submittable. As Jack explains to the hotel manager when he takes the job, “I’m outlining a new writing project and five months of peace is just what I want.” But, as you probably know, that’s not quite how it plays out.

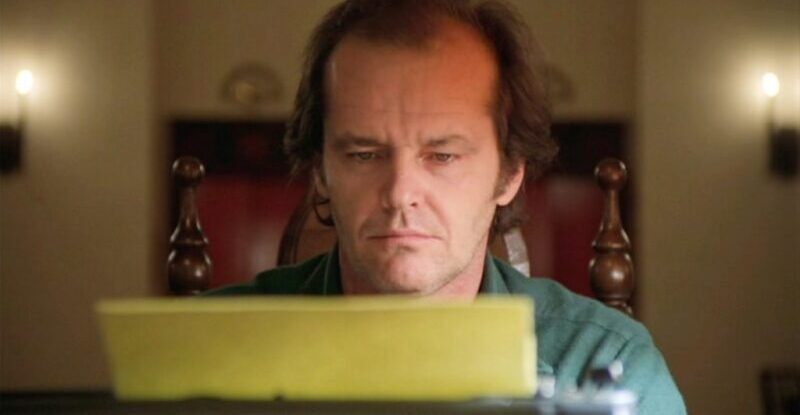

I watched Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror film The Shining for the first time in October 2020 and I was surprised by how much of the film recalled my own writing experience from a few months earlier (minus the violent murders). Just as Jack walks back and forth through the huge lobby of the Overlook hotel, I paced my one-bedroom basement apartment in Cincinnati, confined due to the pandemic and desperately trying to start my first novel.

Especially in the beginning of the film, Jack’s crankiness comes from his character, not supernatural forces. Some of his curt responses to his wife Wendy’s well-meaning inquiries are even relatable—no writer wants to answer the questions, “Got a lot written today?” or “Any ideas yet?” And when Wendy suggests that Jack let her read his pages, he makes up a new rule: “Whenever I am in here and you hear me typing, or whether you don’t hear me typing, whatever the fuck you hear me doing in here, when I am in here that means that I am working.” Of course, it’s an overreaction, and Jack Nicholson’s menacing grin and quirked eyebrow only add to the threat, yet part of me understands his frustration.

When the possibility of failure is tied to your identity, you push the limits to get the grades, to write better, to turn yourself into a success.

I, too, have felt that intense misdirected anger when someone has interrupted my writing flow—lack thereof. The horror of Jack Torrance lies in his humanness—something that Stephen King famously criticized about the film saying, “Stanley Kubrick saw the haunting coming from Jack Torrance, whereas I always saw it from outside.”

*

Here’s the thing about using self-hate as a motivator—sometimes it works. When the possibility of failure is tied to your identity, you push the limits to get the grades, to write better, to turn yourself into a success. After all, isn’t a self-sacrificing work ethic at the heart of the American dream? In graduate school, I wore my bad habits on my sleeve. I told my friends, sometimes jokingly, that if I didn’t have a book published by the time I was thirty I would kill myself. I pulled all-nighters regularly, pouring cold water on my head and pinching or slapping myself to keep awake. I sent a Snapchat of myself lighting my novel pages on fire.

In the midst of studying for my PhD exams, my partner overheard me talking to myself as I struggled to take notes on the books I was supposed to have read by then. A mumbled monologue that I repeated to myself whenever I felt like I was slipping: You’re never going to finish reading these books. You’re not smart enough to have a PhD. You’re a fraud. Stupid. Worthless. An idiot.

“It’s how I motivate myself,” I told them, defensive and curt when asked why I couldn’t be kinder to myself. “It’s the only reason I’m here. It’s driven me to where I am.”

I was insistent that my coping mechanisms worked just fine, not dissimilar to when Jack snaps at Wendy for bringing him lunch in The Shining. He doesn’t want distractions or to leave the hotel, even though it’s giving him nightmares and driving him mad. He just wants to be left alone so that he can write.

*

Critics of The Shining are quick to point out the flatness of Kubrick’s characters. Again, King critiques the film saying, “Kubrick seemed to be in charge of an ant farm. He had turned his people into ants, saying, ‘Well, what happens if they do this? What happens if they do that?’ I didn’t care for that.” It’s true the film’s characters are defined by simple traits: Jack is ambitious and menacing, Wendy is timid, accommodating, yet also capable as she keeps the whole hotel running while Jack’s preoccupied with writing, and Danny is a quiet child with telepathic abilities who explores forbidden hotel rooms on his tricycle. Yet I’d argue that creating full, round characters was never truly Kubrick’s aim.

In her essay on fairy tales, “The Child and the Shadow,” Ursula Le Guin writes that intentionally flat characters are often used to symbolize “timeless archetypes of the collective unconsciousness” and reveal the “incredible potential for good and for evil in every one of us.” Using psychologist Carl Jung, Le Guin explains that shadow characters appear as representations of the dark qualities that exist within us which we do our best to suppress or deny.

When I watch the film, I imagine the characters as psychic archetypes—Wendy, the caregiver; Danny, the explorer; and Jack, the “shadow.” They are all pieces of the self. The Shining is about more than just a man terrorizing his family—it’s about the violent, ambitious thing within us that threatens to kill the other parts of the psyche.

*

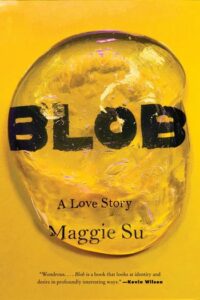

Something I don’t tell people about the process of writing my debut novel, Blob, is how intertwined it was with self-harm. During the worst days of stress and overwhelming pressure, I would lay crying in the fetal position on my rug, curl my hands into fists, and hit myself in the head as hard as I could. It became a habit that eventually led to a concussion.

It took hurting the person closest to me to realize that the same “shadow” that I credited with my biggest writing successes was also killing me.

Like many people who struggle with their mental health, it was hard for me to understand that anything was wrong with me. On some level, this is how I had always operated—that self-hating darkness made me who I was. It’s a problem that I share with Vi Liu, the depressive, snarky protagonist of Blob. After reading one of my early chapters, my dissertation director Leah Stewart asked me, “Don’t you think you’re being too hard on Vi?”

Truly, the thought hadn’t occurred to me—if anything, I thought Vi should be punished more. I hadn’t taken a step back from the page to cultivate empathy for her—or myself. It took an external factor, my professor’s simple inquiry, to reshape the trajectory of the novel as well as my understanding of my writing process.

Still, I didn’t get help. Not until my incredibly empathetic partner (now, spouse—thanks for sticking with me, Andrew) broke up with me to protect their own mental health. Only after losing the person I loved did I go see a psychiatrist, a therapist, and get prescribed an anti-depressant. It took hurting the person closest to me to realize that the same “shadow” that I credited with my biggest writing successes was also killing me.

*

The irony of The Shining lies in the behavior of its director Stanley Kubrick, a notorious perfectionist who demanded 127 takes of a staircase scene where Shelly Duvall (Wendy) swings a bat and cries hysterically as she runs away from Jack Nicholson. While Duvall defended Kubrick’s unusually cruel methods in a 2021 Hollywood Reporter interview, the trope of the “creative genius” using whatever-means-necessary to get a performance from an actor can’t be untethered from the film itself. Is Kubrick’s behavior so different than Jack’s obsessive tendencies or my own unhealthy writing processes? I wonder how much of himself Kubrick also saw in Jack.

Of course, by the end of the film, we realize that Jack hasn’t been writing The Next Great American Novel after all. The camera zooms in on Wendy as she flips through page after page of Jack’s typed manuscript. All it contains is a single childhood proverb: “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” The phrase is fitting as Jack’s clearly become unbalanced and soon after Wendy’s discovery, he begins a murderous rampage. It can almost be read as a parable: lack of attention to the more vulnerable parts of himself (Wendy and Danny) leads Jack to his demise: lost and frozen in a hedge maze, unable even to retrace his steps.

Yet the last image of The Shining eerily cements Jack as the eternal caretaker of the hotel and its violent history. Just as part of Jack will always remain at the Overlook, my shadow is still part of me. The most detested parts of the self don’t go away but they don’t have to control us. With the support of loved ones, therapy, and meds, I can allow Danny, the empathetic explorer, and Wendy, the nurturer, into my workspace. I can try to quiet the fear of failure. We all can.

__________________________________

Blob: A Love Story by Maggie Su is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Maggie Su

Maggie Su is a writer and editor. She received a PhD in fiction from University of Cincinnati and an MFA from Indiana University. Her work has appeared in New England Review, Four Way Review, TriQuarterly Review, Puerto del Sol, Juked, DIAGRAM, and elsewhere. She currently lives in South Bend, Indiana, with her partner, cat, and turtle.