Ivonne Lamazares on Crafting a Story of Family, Identity and Belonging in Cuba

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “The Tilting House”

Ivonne Lamazares’ The Sugar Island captures Cuba in the 1960s not long after the Revolution, as the backdrop to a coming-of-age tale in which a daughter is at odds with her mother, who wants to emigrate to Miami. The language is crisp, the conflict clear from the beginning: “‘Listen to me,’ Mama commanded…‘This country is just a backwater plaintain grove. Now and forever….Tanya, mija, our life is about to start.’ Mama always wanted to start life just as I wanted to start a new notebook at school, with neat and crisp lines, waiting to be filled in with important dates and bright colors.”

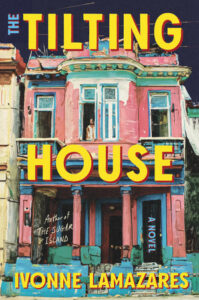

Lamazares’ engrossing second novel, The Tilting House, brings the timeline to 1989, when Soviet support for Cuba was withdrawn and the “special period” of deprivation and struggle began. It’s a multilayered, multigenerational novel, with a winning narrator and a nuanced and authentic portrait of Cuban culture then and now. Hovering over the unfolding events is the ongoing question of what it means to leave one’s birth country and relocate to another.

What propelled her to write this novel? I asked Lamazares.

“I had come across a blog in which a Cuban American writer was discussing her decision to return to Havana to live there permanently,” she explained. “Clearly this wasn’t the usual trajectory of migration many of us are familiar with, and it raised a number of questions for me that wouldn’t go away. I kept asking myself, what is an immigrant seeking in returning to live in their country of origin, in this case Cuba, an island suffering from severe economic scarcity and political repression, even outright censorship? And soon the character of Mariela appeared—a 34-year-old Cuban American artist, sent as an unaccompanied four-year-old to the U.S. and raised in a Nebraska orphanage, coming back to the island in the 1990s to recover her Cuban origins and become part of a home and homeland she felt she was cut off from.

As she wrote more, other questions arose, she continued. “…such as whether any of us can ultimately recover our origins as Mariela seeks to do, and in an attempt to recover those origins, what disruptions may occur, what unintended consequences, especially when someone goes back to join a family dynamic and culture and history they were never a part of. What does the arrival of immigrant Mariela do to the family that stayed in Havana, for example?

“And as I wrote about the Cuban family Mariela is coming back to, the voice of the narrator came to me—a 16-year-old girl, Yuri, whose mother has died recently and who lives now with her strict, religious Aunt Ruth in the fictional Havana suburb of Paladero when Mariela returns to Cuba. Mariela and Yuri turn out to be half-sisters, raised in entirely different worlds with completely different personal histories. The guiding question for me then became, what would Yuri and Mariela make of their sudden ‘sisterhood’?

“Through their fraught relationship, the novel set out to explore ideas of home, nationhood, family narratives, and identity. Where is home, especially for an immigrant, and in this case an orphan raised far away from her original culture and family as is Mariela in the novel? How do we immigrants (and all humans for that matter) integrate a difficult past with our present, especially if there is trauma, loss, oppression, and disruption of family relationships? How do we come to give justice to ourselves and to each other and to integrate those experiences compassionately into who we are today?” Our email conversation spanned the continent, from Miami to Sonoma County.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did your own experience, being born in Havana, having left Cuba in your early teens and settled in Florida, shape this novel?

I’m endlessly curious about the ways in which people integrate and reconstruct their narratives after major losses.

Ivonne Lamazares: The events in the story are not autobiographical, but parts of the emotional trajectory of the two sisters echo my own. Yuri begins narrating when she’s about the same age I was when I migrated to the U.S., and I found that I had to write from that moment of migration, a time in my life of great vulnerability and disorientation and possibility.

When I migrated to the U.S. with my father’s parents, I experienced, like Yuri, a radical rewriting of my family’s narrative. My mother died when I was three, and I had been told that in migrating to the U.S. I would reunite with my biological father. He had left Cuba when I was six. My grandparents, too, would reunite with their only son. We would become a family, and I would live with my surviving parent. I longed for this, naturally. But my biological father abandoned both me and his parents once we arrived in Miami, and when he resurfaced sometime later, he was abusive and our relationship ended.

As in Yuri’s case, it took me years to process the collapse of the family narrative I’d grown up with. I’ve been lucky to gradually move, with the support of many, from surviving to emotionally thriving.

JC: Why did you decide to call this novel Tilting House?

IL: The novel begins in 1989, when the Berlin Wall falls and the Soviet Union collapses. This event has global consequences, and for Cuba, it triggers a huge economic crisis on the island as the substantial Soviet subsidies that kept Cuba’s economy afloat suddenly disappear.

The entire world in the novel, and the characters’ lives, are in constant motion; political, economic, and family relationships shift and reverse and collapse. The tilting house of the title also represents for me the unstable, constructed nature of identity. Immigrants (and orphans—it’s something both groups seem to me to have in common—) experience firsthand this tilting or shaking or sometimes outright destruction of the foundations of who we thought we were. I’m endlessly curious about the ways in which people integrate and reconstruct their narratives after major losses. And it strikes me that the opposite belief, that our identities, personal and national, are fixed and immovable can lead us to some pretty malignant actions that dehumanize any “other” that dares to cross our border.

JC: Why did you choose to set most of this novel during the “Special Period of terrible scarcity,” a time of hunger after the collapse of the Berlin wall, a time when “Soviet goods had disappeared from store shelves and neighbors had found themselves scraping together strange dishes of ground soy protein mixed with cow organs”? How would you explain that era in Cuba to readers who are unaware of what happened then? Were you in Cuba at that time?

IL: I didn’t live through the “Special Period” of the 1990s in Cuba, but I set the novel in this era because it was a time of hope, instability, and extreme need on the island. Some thought Cuba would open itself up to democratic reforms; others even hoped for regime change. Of course, these things didn’t happen. But other changes did. For the first time Cuba allowed more visitors from abroad, particularly Cuban Americans, and encounters between the Cuban diaspora and Cubans living on the island began to happen. I was fascinated by some of the consequences. For one, the economic power of the “traitors” who’d left became real to those still living on the island. Special shops opened up where goods unavailable to the general population were sold only in U.S. dollars, and suddenly a revolution that had billed itself as an anti-colonialist, socialist, egalitarian movement, was restructuring itself around the power of money and acquisition. Social class differences were no longer based on political affiliation (as in during Soviet Cuba) but on economic privilege, i.e, access to dollars. Cuba began to attract international tourism, and with it, the government created a sort of tourism apartheid, whereby Cubans were not allowed to enter resort hotels where foreigners sunbathed and drank mojitos by the pool. In the meantime, Cubans without generous, dollared relatives abroad hustled for food and basic necessities, as scarcity and malnutrition reached extreme levels at this time.

Conveying such realities to readers who live in the developed world of global capitalism while at the same time not betraying the perspectives of my Cuban characters is a huge part of what I want to do as a writer. While writing this book, I worried about immigrant characters sometimes being presented in fiction and in the media as unidimensional victims or as blank slates, beings without a history or past that should concern citizens of the adoptive country. But of course this worry of mine now feels like chump change in the face of Alligator Alcatraz and other holding hells for immigrants who might be shipped off to prisons in South Sudan or El Salvador. At this moment it’s simply imperative to write and speak and hold up the humanity of immigrants through any means. Fiction is one of those means, I hope.

JC: Why did you choose to name Yuri, your primary narrator, after the Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin, the world’s first man into space?

IL: Names starting with the letter “Y” were quite popular in Cuba during the 1990s. But I also liked the idea that Yuri would have a name she feels ambivalent toward, which conveys an already uncomfortable sense of herself and her history. For one, Yuri is usually a boy’s name, and in the novel this choice of name reflects a socialist commitment by Yuri’s mother and father during a time when Cubans were urged to look toward the Soviet Union as a model to aspire to and as a protective neocolonial power. Once Yuri migrates to the U.S., her name feels like a burden to her; it links her to an anachronistic time of Cold War and Special Period and to the aspirations of a gone world, the Soviet world. I also liked the irony of cosmonaut Gagarin, first human in space, dying in a routine flight accident, as this reflects Yuri’s experience of sudden, absurd loss, given her own mother’s untimely death.

JC: Yuri sees a stranger at their door and meets Mariela, a returnee to Cuba who had mostly grown up in “la yuma,” or the United States. Ruth says Mariela is her child, but she may be Yuri’s sister, not her cousin. Yuri is sixteen, Mariela is thirty-four. There is tension between them. Would you call that sibling rivalry? Yuri envies Mariela, who has more agency, more assets, and maneuvers their circumstances so they are living in a privileged apartment with Mariela hosting salons offering the best food and drink available through black marketeers? And Yuri also sees Mariela as an obstacle to her own urge toward independence (“I wanted my own fate—not one latched to hers out of desperation”).

IL: The complex relationship between 16-year-old Yuri and 34-year-old Mariela drives the plot and was my central focus in writing the novel. I was very interested in depicting two people who share some of the same grief, the loss of a common mother, and who so often seem unable to find solidarity. The two sisters grow up in different worlds and their personal and national histories collide. Mariela, who has grown up in a Nebraska orphanage and briefly in a foster home, wants to leave her mark in the place and family she feels she was denied. As an artist, she’s determined to carve and paint and create performances and shoot rifles and use gunpowder to explode homemade little rockets in her “homeland.”

But having grown up in the U.S., Mariela is clueless about the limitations on art making and self-expression that exist on the island, and her projects and sometimes reckless behavior upend Yuri’s and Ruth’s lives. Yuri is unsure of Mariela’s motives, and she resists Mariela’s version of their sisterhood. Yuri has memories of Mamá, and Mariela’s desire to absorb Yuri into her own story threatens Yuri’s sole ownership of her grief. This inability to establish solidarity in a common loss echoed some of my experiences as a child. I had a hard time expressing and owning the loss of my mother in the presence of my grandmother’s all-consuming suffering over her daughter’s death. I wanted to explore this emotional paradox in the novel.

JC: What research was involved in writing about the “Pedro Pan” operation that sent Cuban children like Mariela to the United States in 1962, for what was expected to be a brief safe stay, but became permanent after the Cuban Missile Crisis? And about Mariela’s experience in Nebraska as a foster child for a year, then at the Catholic orphanage where she grew up?

IL: I read a number of memoirs by Pedro Pan adult children, for example, Carlos Eire’s Waiting for Snow in Havana, and others. I’m also lucky that, living in Miami, I’ve met and talked to a number of Pedro Pan adults and attended presentations and films and discussions about this wave of migration. I didn’t want to appropriate the Pedro Pan experience, and I hasten to say that Mariela is a fictional case out of the 14,000 unaccompanied children who migrated then, so her situation is unique and not representative of any group. At the same time, I wanted her experience to reflect some of the feelings of loss and shock expressed by some Pedro Pan adult children. The experiences of these children were of course diverse; some stayed with relatives in the U.S.; some were reunited more quickly with their parents than others, and some lived longer in foster homes and orphanages. Some suffered abuse and feelings of abandonment. Unfortunately, some of this history seems relevant now as immigrant children are being forcibly separated from their parents.

JC: Mariela is an earth artist who has already exhibited widely and immediately attracts a group of Cuban artists. Was Ana Mendieta an inspiration? How did you develop the details about Mariela’s work and about the artistic community in Cuba that welcomes her, including painters and sculptors from Havana’s Art Institute; actors, directors, and scriptwriters from the Cuban Cinematographic Arts and Industry, and journalists from the National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists?

IL: You’re right that Ana Mendieta’s art, especially her work in Cuba, was an inspiration to me, as was Cuban artist Tania Bruguera’s. But Mendieta, as far as I know, didn’t shoot at her creations with a modern weapon, and this was something that I felt Mariela was compelled to do. For the Nadies figures that Mariela creates and then shoots at and partially destroys (Nobodies, or as Mariela calls them, Forgottens), I was particularly inspired by Niki de Saint Phalle’s shooting paintings. I was also inspired by the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, who uses gunpowder and creates explosions to explore themes of destruction and transformation. Mariela’s shooting performances (all fictional) seemed to me to speak to her desire to create and destroy at the same time, to defy and also to reenact her losses. She also identifies these figures with the Taino and African goddesses lost through colonialism, and she attempts to connect her own lost personal history and orphanhood with the larger history of genocide in the Americas.

I had read memoirs and accounts of meetings and interactions among painters and sculptors and some of the artistic community that Mariela finds in Havana, and I met a few of these artists in Miami, but for the novel I imagined these characters. I imagined Mariela encountering both solidarity and the otherizing and sexism that I observed at times in these art communities, particularly in the 1990s.

JC: Yuri follows Mariela to New York City and begins to build her own life. She becomes a regular at the Forty-second Street Library, learning English by reading and being in crowds and restaurants. Does her life echo your own experience?

IL: In some ways. Like Yuri, I also sang along to the radio’s Top 40 and tried to produce the sounds I heard without understanding many of the words I was singing. But I had a slightly easier path than Yuri’s in that I landed in an ESL classroom in Miami with other just-arrived immigrant teenagers and I didn’t feel as alone. I was able to pick up enough English by the time I went to high school, and there, a kind counselor decided to put me in honors English. I had a hard time in the class, and my pronunciation of Wordsworth and Shakespeare was abominable, but through reading and writing and listening hard to conversations around me, like Yuri, I learned the language. Books were a lifeline for me, as they are for Yuri; they provided stability and escape. At that time my father’s mother and I lived in a tiny apartment in Hialeah paid for by welfare checks, where my often drunk father would crash whenever he felt like it. Abuela and I shopped with food stamps and went to the doctor with Medicaid cards. I’m forever thankful to have had this assistance in those first years of migration.

JC: Yuri becomes a reporter for Reuters-Latin America, and returns to Cuba to report on the re-opening of the U.S. Embassy in Havana in 2015. How did you arrive at this return as the end-point for your novel?

The way to healing might be justice—but how can we give ourselves and others justice when judgment is not entirely possible?

IL: At some point, I was stuck in the writing of The Tilting House. Because I had been away from Cuba for 36 years, I couldn’t tell if I was doing justice to the characters on the island or to the novel’s returning Cuban American immigrant sister. I knew that going back to Havana would be emotionally fraught for me; I also worried about the risks of returning to a society that doesn’t recognize basic liberties and rights. But in the end I visited Havana in 2012, and that visit was significant, both for the writing of the book and for me personally. I thought seeing the familiar landscapes and places would give me the key to finish the book, but some of those places had changed drastically, as in the case of my grandparents’ home, which had been divided into two dwellings. So seeing those places again brought me mostly dissonance, and afterward, I kept remembering them as they used to be, so some parts of Havana now exist for me only in my mind.

But in that visit, the people and my encounters with childhood friends and the warmth and generosity that Cubans have with one another, that familiar way of communicating, gave me a way forward to the novel’s ending. It was like a musical key that I hadn’t heard in many years and that I recognized immediately as right and true, and one of the most important things I’d missed in my life in Miami, without even knowing it.

I realized then that at the end of the book Yuri had to return to Havana to try to find, like a detective, the missing pieces to the puzzle of her past. Like Yuri, I also hadn’t been able to fully grieve my mother, and it was in that visit, after going to my mother’s grave and feeling that grief as an adult that I understood emotionally where Yuri’s journey might be heading.

JC: At one point Yuri notes, in describing her mother (their mother) to Mariela, “Little by little, I started to lie….I gave wrong names and dates on purpose….By lying to Mariela, I thought I’d keep something of my life with Mama to myself. But as I spoke, the fake memories started to edge out the real ones and I worried I wouldn’t be able to tell from then on which details I’d invented…” How is it possible for Yuri to know which of her childhood memories is true or false? How can Yuri know which of her family, friends and neighbors tells the truth, when the consequences can mean deprivation or jail? And upon her return, how is it possible for Yuri to know which of her childhood memories is true?

IL: I’m so glad you asked about this, because it’s a crucial point in the novel. The instability and fluidity of memories, of our relationship to the past, and ultimately of identity and home emerge at this point in the narrative as one of the important themes of the book, at least for me, and I hope for the reader as well.

Truth is elusive throughout the novel—the shifting narratives and stories around Yuri are extremely confusing to her and difficult to reconcile. Yuri struggles to find “proof” that Mariela is indeed her sister; she fights to pinpoint the charges against Ruth after Ruth’s mysterious arrest. Yuri is also not sure what exactly brought down Ruth’s house. These shadowy events with no clear causes or culprits create in Yuri a terrible confusion and inchoate rage. Sometimes I feel a little bad for what I put her through in the book. But because fiction is a sort of laboratory, or a pressure cooker, Yuri keeps searching and asking, even if some of her questions might be ultimately unanswerable, as facts can only go so far. The way to healing might be justice—but how can we give ourselves and others justice when judgment is not entirely possible?

I remember that Honors English teacher, Mrs. Gannett, in my high school, when I could barely read English novels, sitting on her stool, pulling her graying hair back with her hands as she searched for a way to explain to us immigrant teenagers what was going on with Kurtz in Heart of Darkness. She tried to tell us why the narrator Marlowe concludes that murderous, mad-king Kurtz had “no restraint.” And then the teacher asked, “And what is Marlowe’s restraint?” I remember sitting on the edge of my seat; I burned to know. I thought that something crucial about my life was going to be revealed. And Mrs. Gannett said, “Marlowe’s restraint is compassion.” Ah. Yuri has to get to compassion eventually, as I suppose we all do, if we work hard and are lucky.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

IL: I have started working on something that I’m excited about. The story takes place in Miami, in the Hialeah area where I lived when I first migrated. I think that the story will travel also, like The Tilting House’s, backward and forward in time and geography, between the U.S. and Cuba. But I see this new book exploring the Cuban American community in Miami a bit more closely.

__________________________________

The Tilting House by Ivonne Lamazares is available from Counterpoint Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.