It’s the Most Important Muscle in Your Body and You Don’t Even Know What It’s Called

Henry Abbott on the Essential Anatomical Role Played By the Enigmatic Psoas

“Where you think it is, it isn’t.”

–Ida Rolf

*

On my first trip to Santa Barbara, Dr. Marcus Elliot walked me to Peak Performance Project’s sister business, the Lab, which is sometimes referred to as “P3 for normies.” There I met Mike Swan, the physical therapist who rented Marcus the floor space where P3 was born, and who has earned a reputation as a high priest of soft tissue. (I once watched a woman, who had been scheduled for back surgery, undergo one session with Mike, then stand up and say she felt all better.) About four minutes after meeting me, Mike told a very unsurprised-looking Marcus that I lacked hip mobility.

Marcus nodded, smiled, said, “Good luck,” and walked out.

At that moment, I would have described myself as an atheist, unsure there was such a thing as a human soul. Then Mike jammed eight clarifying fingertips into the front of my right hip: Yes, I do have a soul, and Mike is choking it. My heart rate spiked, sweat gathered at my temples, my sense of humor crumbled. After thirty seconds, when I thought he might wrap it up, Mike took a wistful glance at the clock and lamented that we only had twenty minutes left.

That, Mike said, was my psoas.

“Huh,” I said, between labor-and-delivery exhales. “I thought the psoas was in the back.”

I knew about visible muscles like biceps and quads, but had mostly ignored the invisible ones that keep us running.

“Oh, it runs back there,” Mike said. Then he demonstrated its shape by fluttering his hands like My Octopus Teacher.

As Mike spoke, I was decades into caring deeply about athletic bodies. I knew about visible muscles like biceps and quads, but had mostly ignored the invisible ones that keep us running. Studies have correlated a weak psoas with bone wasting, surgical complications, poor prognoses in cancer treatment, and—amazingly, and for reasons that aren’t well understood—death.

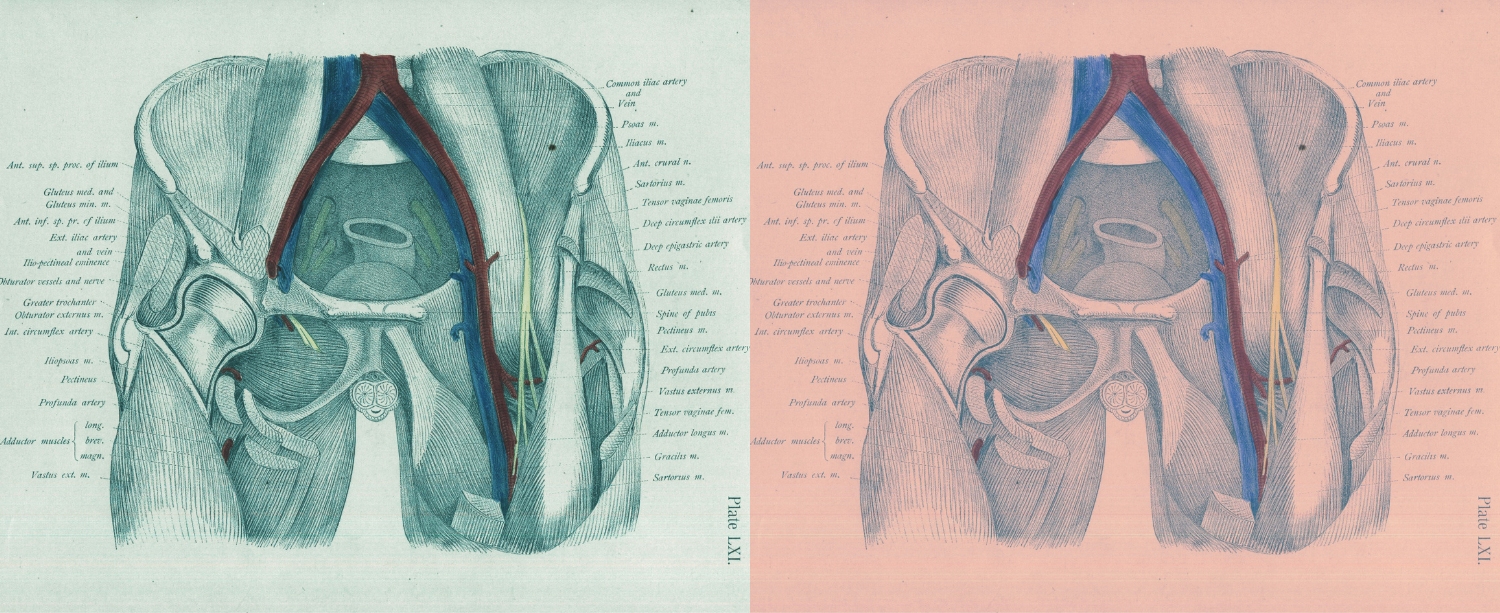

The psoas works hard. It’s the only significant muscle that exists both in the top and bottom halves of the body, and also the only muscle that truly moves around the body’s center of gravity, where it stabilizes both the lower spine and the head of the femur. It’s the most important of all the hip flexors, which are the muscles that pull your leg up in front of you, as if to hurdle. It’s integral to posture, walking, running, lifting your body off the ground, and moving laterally. It’s also connected to the neighboring abdominal muscles and diaphragm, meaning the psoas has a deep back-and-forth with respiration.

Somehow, that’s not all. The psoas is latched tightly and intricately to the discs, vertebrae, nerves, and blood supply of the back’s bottom six vertebrae. The nervous system manages the entire lower body through an intricate web of nerves called the lumbar plexus, which is embedded through the psoas. The psoas looks, on an MRI, like a nerve center weaving through the kidney’s intricate systems, the diaphragm, the esophagus, the intestines, the sex organs, and the pelvis’s many wonders. The psoas might be the body’s deep state.

Modern MRIs give researchers highly accurate ways to measure muscle volume. The deltoids at the top of the shoulder, for instance, average 380 cubic centimeters. The triceps are almost as big, followed by the pectorals on our chests, which are typically 290 cubic centimeters.

The psoas clocks in with an average volume of 407 cubic centimeters. It’s huge, and most of us have no idea where it is.

Lie on your back and find the knobby bone on the front of your hip. Now let your fingertips walk a tiny step into the soft tissue in the bowl of your pelvis, and press down. If you’re in the right spot, as you lift a foot slightly off the ground, you’ll feel something like a bass string pressing into your fingertips. That’s your psoas saying hello.

From under your finger, the psoas travels to interesting places. Mostly, it plunges through the innards behind your belly button to grab the inside of your lower back. When you sit up straight, the psoas pulls your lower back forward, from the inside.

At the hip, the psoas joins forces with the iliacus, a muscle emanating not from the inside of the spine but from the inside of the pelvis. Together they have much to say about your posture, gait, and movement.

The iliopsoas also travels to a more secluded spot. If you’re curious, alone, and not squeamish, put your hand in your groin muscle, and dig around until you find the femur beneath. Follow the femur up, and up a little more. Near the top, there’s a knob. When your fingers find it, you’ll be in a prizewinning crotch grab. That’s where the iliopsoas attaches.

This muscle is central to our multifaceted disability crisis. “An estimated 619 million people,” says the World Health Organization, “live with lower-back pain and it is the leading cause of disability worldwide.” A growing body of research shows that those people tend to have measurable atrophy or weakening of hip muscles like the psoas. Unsurprisingly, the psoas tends to get weak and stiff from sitting—and sometimes angry from running, biking, or swimming.

Psoas workouts are a hornet’s nest of theory and opinion. In video footage, mixed martial arts fighters train by scrambling around on all fours like wild creatures, heavy with psoas-rich movements like pulling your knee close to your chest. (We evolved cooking, eating, and socializing in positions like that. Perhaps psoas workouts are a return to normal.) Impassioned essays implore you to stretch your psoas; other impassioned essays implore you not to. Even at P3, I’ve heard trainers saying that stretching a psoas sometimes angers the thing.

There’s broad agreement that a strong psoas tends to be happier than a weak one. While at P3, Mexican professional soccer player Juanjo Purata does a lot of exercises with a “march” component, which means pulling your knee up proud and high—using your psoas—as you stand on one leg. In one variation, Purata marched up and down the track with a heavy kettlebell at his side like a suitcase and a soft medicine ball held aloft in the palm of his other hand. Later, he chest-passed a medicine ball to himself off the wall, again and again, with a leg up high in the march position. At P3 they also find that, after an array of hip work, clients tend to be able to raise their knees higher toward their chest.

Glute work also seems to help the psoas. Many of P3’s exercises work with the agonist/antagonist principle—it is well established that some of the body’s muscles are neurologically paired so that as one contracts, the other relaxes. That’s why a yoga teacher might say to tighten your quad while stretching your hamstring. The psoas operates largely opposite the glutes, which is why Purata paired his march movements with glute work. He sank his hips back into a squat with resistance cables running from each hand to the Keiser machine, and then in one exciting thrust, he pulled the cables to his chest as he snapped his hips straight. He did Romanian dead lifts on one leg, but instead of lifting a weight from the floor, he pulled a cable from the Keiser machine in front of him. The wide world of psoas therapy looks a heck of a lot like all the work P3 does to develop the posterior chain. Squats, step-ups, jumping forward against a band, pushing a sled, hill sprints—everything that gets your hips strong, extending, moving with range, attenuating force—tends to also help your psoas.

When elite five-kilometer runners added hip flexor exercises to their routines, MRIs found that increases in psoas size correlated nicely with faster times.

A simple way to check in with your psoas: Stand on your left leg and raise your right knee as high as it’ll go under its own steam. If you sit a lot, it might stop parallel to the floor. If the P3 coaches saw that, they would quietly make plans to get it higher.

With your leg up, test your hip’s rotation. Picture your knee pointing at the center of an imaginary clock on the wall in front of you, while your right foot dangles at thirty minutes past the hour. Keeping your hips straight, sweep the foot clockwise as far as it will go, and then counterclockwise. Experts suggest that between those two moves, you ought to be able to sweep fifteen minutes, commonly from twenty to thirty-five minutes past the hour. If you can’t, you might have a bony limitation, weak muscles, or the need for myofascial work.

Marcus doesn’t drink much caffeine—typically a single morning cup of green tea. But one afternoon, he started messing with P3’s espresso machine. By the time Eric saved him, he had commingled decaf beans with regular. (As he fished the decaf back out, Marcus asked, to no one in particular, “Why do we even have that?”)

After a strong espresso, Marcus talked fast about the perils of being tight in the front of the hips. He had just met a low-ranked but high-hoped professional tennis player. He tested as an exceptional athlete—six feet, four inches, with long arms, 205 pounds of lean muscle—except for one thing.

“Laterally,” Marcus says, “he’s terrible. He can’t create force out of his hips.” The player’s anterior hips were so tight that the strong muscles that would move him side to side were essentially unavailable. A number that matters to Marcus is newtons per kilogram—the force you generate, divided by your weight. In an embarrassed whisper, Marcus disclosed that this player generated a mere 7.4 newtons per kilogram in the lateral skater. This guy’s trying to support himself playing tennis, has a coach, and works out constantly, Marcus explains—and laterally, he generates the newtons of a middle-schooler. “He’s got a peashooter for hip extension,” says Marcus.

“We’ve done in-house research on mobility,” Jon says. The news is mostly good. “And what we have found is that anterior hip mobility is very plastic; it can change quite easily.”

“Your body,” says Marcus, “is crazy adaptable.” One of the ways P3 would adapt that player is with the move that made me consider the divine: the psoas release. Peer-reviewed research has been so-so on the long-term effects of myofascial work. A recent survey found the available studies “mixed in both quality and results,” but ultimately “encouraging.” But in Marcus’s view, well-applied myofascial release can make the difference between making it in professional sports or not.

That might be surprising if you’re used to thinking of a body through the lens of bone bias. X-rays have been around for a long time; bones are clearly diagrammed, stable, conceptually like the two-by-fours that frame our houses. “Did you break it,” they ask, “or just sprain it?” The implication is that real injuries happen to masculine and well-defined bones, while soft tissue seems more feminine and mysterious. Meanwhile, our upper and lower halves are held together only by ligaments, tendons, and psoas.

The psoas release is a minor miracle. For all its grimy emotions, the aftermath comes with the divine feeling that your hips have returned to their rightful place. Under a YouTube video showing rudimentary psoas maintenance, commenters find they need all-caps: “LIFE CHANGING. This was the stretch missing in my life!!! THANK YOU,” says one. “No lie after about 5 minutes I feel SIGNIFICANT relief from a problem that has literally plagued me for years,” says another, while a third notes, “I simply CANNOT overstate how amazing the difference has been.”

We are all Marcus’s tennis player, lacking this aspect of hip enlightenment. “He needs to develop some self-care,” Marcus says. “He’s got to work on mobilizing, stretching all the anterior hip muscles, all of his quads,” says Marcus. “And he can get a thumb dropped on him at least once a week.” It upset Marcus that the player had gone twenty-four years, and played four years of high-level NCAA tennis, but still awaited his first psoas release. “Like, how does that not happen?”

You can release your own psoas. The Lab teaches first-timers to use a hard medicine ball, about the size of a volleyball. I bought one at Walmart for twelve dollars. Get in the plank position, press the psoas on the front of your hip into the ball, and then sink your weight into it. The Lab’s take-home instructions specify “raise leg to dig in further.” When you find the right spot, it feels wrong.

Or, lie on your back with a lacrosse ball on your psoas, and then rest a heavy dumbbell on the ball. Some people prefer the twenty-three-dollar psoas release device shaped a bit like a cane with a hard ball affixed to one end. Lie on your back, jam the rounded end into the front of your hip, and it’ll give you a sense of meeting Mike. I like to apply the pressure where Mike did, just inside the pointy hip bone, but others prefer an inch or two higher, toward the belly button.

One early morning, I joined Eric for an employee-hour workout. I asked if P3 had a psoas stick I could use. Eric handed me seven feet of dense wood, a wizard’s staff with a ball affixed to one end.

As Eric resumed his workout, I lay down on my back and jammed that massive tool in place with two hands. When Eric caught sight of my little scene, his face erupted in delight. “What,” he asked, “are you doing?”

Only then did I grasp the absurdity of waggling a seven-foot wizard’s staff from your crotch halfway to the ceiling. Eric took the thing, walked to the wall, and calmly demonstrated how it’s actually used. Stand up, plant one end of the stick in the crease where the floor meets the wall, and lean your psoas into the ball on the other end. Incredible.

P3 tries to help athletes find good soft-tissue workers all over the world. It’s mostly trial and error, but the CEO of the Lab, Alex Ash, says he looks first for recommended “orthopedic physical therapists,” and failing that, Rolfers. They have no interest in spa-type comfort. This is about joint function.

One of the Congo’s best-ever basketball prospects is six-foot, eleven-inch Tichyque Musaka. When he first came to P3 in the summer of 2022, he raised eyebrows with an incredibly low-tech hip mobility measure: He lies on the physical therapist’s table, face down, while Eric pushes his heel toward his butt. At a point that Eric swears is precise, he stops pushing, and measures the distance, in inches, from butt to heel. The “heel test” is the most kindergarten-level datum in P3’s futuristic array, and important. Big changes in this test, over time, can signify serious stuff.

Many athletes can touch heel to cheek, but not Tichyque. On first assessment, he could only get his right heel within seven inches. Eric wrote 7 on the clipboard. After further assessment and some discussion, the team focused on the quad, which evidently had a death grip on Tichyque’s femur.

All that poking into your muscles can be tense, but over time it comes to feel more like an oil change.

Some immobility comes from muscles being a little clingy, like a child scared to let go of a parent’s hand. Sit cross-legged on the floor. If your knees poke up like the hills above Santa Barbara, often it’s because your groin muscles won’t let the femur go.

Active release—essentially pressing with fingers—can quickly help. But, in keeping with the hip’s reputation as a cultural hot zone, the key spot where the adductors grab the femur is at the tippy-top of the groin. When that muscle is seized, P3 teaches athletes to release it themselves. (“Nobody,” Jon points out, “is trying to get canceled.”)

“So, basically,” Jon explains, “you put your actual adductor on the metal handle of the kettlebell and you rotate, flex, and extend….Most people are like, ‘Oh, my God, this feels horrible.’ ”

“Even though research is a little split on foam rolling and self myofascial release…in my eyes, from what I’ve seen here, and what I’ve done on myself, I think it works pretty well,” says Jack. “It creates a window to enhance the ability of the stretch we’re going to do next.”

This is how Tichyque met the quad smash. He sat on the floor with his back pressed to the cinder-block wall, legs straight out in front, as Jon fetched one of the heaviest single items in the gym, a fire truck–red thirty-two-kilogram kettlebell.

Tichyque parked those seventy-odd pounds of cast iron directly on the quadriceps. Quickly, the upbeat demeanor drained from his face. He muttered something to a passing Jon, whose retort was beyond sunny. “BREATHE, BREATHE!” Jon hollered, projecting the opposite of concern. “IT’S GOING TO BE OKAY!!” The first round lasted two minutes.

Later, Jack said that professional athletes generally take this move in stride, but the first time teenagers quad smash, “it’s like they’re being shot.” Tichyque was eighteen.

After Tichyque switched the kettlebell to the other leg, Jack strayed near, and Tichyque spoke through clenched teeth. Jack grinned and gave him a high five.

When that was finally over, Jack and Jon brought Tichyque to a rig set up with the strongest band in the building, a loop of rubber perhaps eight inches across and six feet long. The teenager knelt before the rig like Vader before the emperor, one knee on a pad, the other sole flat on the floor, with the stretched green rubber looped behind his kneeling thigh. The band pulled Tichyque’s femur forward with such force that Jon and Jack held his upper body in place, to keep him from shooting forward. Sweat trickled down Tichyque’s anguished brow.

Like grief, the panic of myofascial release ebbs with time. Every P3 workout features soft-tissue work targeted to the day’s workload. One day’s workout might prescribe a minute each side, so eight minutes total, putting a lacrosse ball into the psoas, glute, TFL, and QL. Another day might pair a hamstring release on the med ball with a banded stretch. All that poking into your muscles can be tense, but over time it comes to feel more like an oil change. Things run smoother. And then, at some point, you get a sense of why Marcus seems to age differently, and better, than most of us. He doesn’t wake up mystified by some fresh hell that has seized his hip. He wakes up thinking, Huh, my psoas is a little tight, and then he addresses it, and it’s better.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Ballistic: The New Science of Injury-Free Athletic Performance by Henry Abbott. Copyright ©2025 by Henry Abbott. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Henry Abbott

Henry Abbott is an award-winning journalist and founder of TrueHoop. He led ESPN’s 60-person NBA digital and print team, which published several groundbreaking articles and won a National Magazine Award. He lives in New Jersey.