“It’s Out of Africa Meets Pretty Woman!” On the Problem With Comp Titles

Maris Kreizman Wishes There Was Another Way

When you’re searching for something new to read there are plenty of signals to let you know if a particular book might be worth an investment of your time: the genre of the book, the cover, the marketing copy and blurbs, the author’s previous work. But very often, especially in books where the quality of the prose is paramount, you can’t tell whether you’ll vibe with a book until you actually, you know, pick it up and start reading it. “Vibes,” of course, are entirely unquantifiable and difficult to replicate, but they’re the most basic part of just about any reading experience.

We all know that corporate America loves data driven decision-making, as if plopping a bunch of numbers on a spreadsheet can guarantee success. But what is a risk-averse industry to do when the products it sells can’t be neatly broken down into data points? In book publishing, we use comparative titles.

Comparing the book you’re working on with other already successful titles is so important, comp titles are ubiquitous in just about every stage of the publishing process. Search around the aspiring-author-internet and you’ll find tons of articles on the comp titles you should include in your query letter to agents: why you need them, how to find them, how to pick the right ones, etc.

Comp titles are also there when agents pitch book projects to editors, and when editors pitch internally to their sales and marketing teams (back in the early aughts, before Bookscan, editorial assistants would email friends from other houses to try to get accurate sales figures on the comps their bosses were hoping to include on their title information sheets).

And that’s not to mention publicity pitches to the media. I searched the word “meets” in my email subject lines and found hundreds of pitches from the past few years that said “X meets Y” like so: “The Lovely Bones meets The Five People You Meet in Heaven,” “The Handmaid’s Tale meets Alice in Wonderland,” “Misery meets Room.” It’s tough, as a critic, to live in a world where any psychological thriller with a twist is the new Gone Girl, or any young female author who writes socially conscious novels about romantic travails is the new Sally Rooney.

There are no easy answers. Describing the vibes of a book—especially in a short amount of time, like in an email or at a sales conference—is difficult.

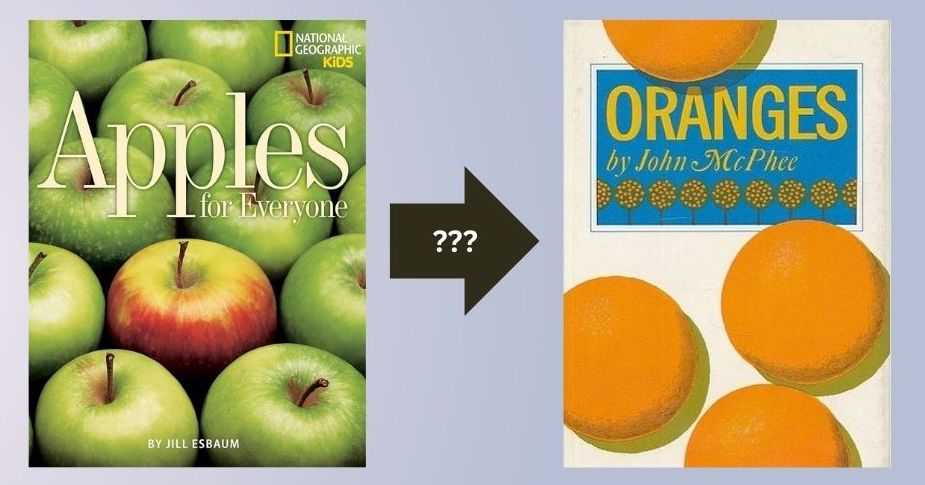

In nonfiction, especially practical nonfiction, comp titles make a lot of sense. If a specific audience bought book A about gardening or how to succeed in business, then that audience would likely also buy Book B on those same topics. But practical nonfiction is also where the most data about books and about particular communities of readers already exists. It’s all of the other genres I’m worried about.

There are no easy answers. Describing the vibes of a book—especially in a short amount of time, like in an email or at a sales conference—is difficult. We absolutely need a shorthand to try to explain the experience of reading a book, and comp titles are as close as we can get. Trust me, I absolutely realize that most new books are not doing something entirely visionary that has never been done before (authors, I understand why you might be tempted to think, “But there are no comps for this masterpiece I wrote,” but you’re likely wrong!).

But such shoehorning means that each new book is likely compared to a relatively small number of other books that came before it and that were successful (however you determine success: by sales figures, exposure, name recognition). What if, instead of contorting new titles to fit into a box of previously published books that did well in some way, there was more space to grow and evolve?

I want to live in a world where “eccentric” and “difficult to categorize” are actually selling points, where “but where would you shelve it in a bookstore?” doesn’t have an easy answer and that’s okay.

Over the weekend I watched The Player, the 1992 Robert Altman film about Hollywood in which the first scene (shot in one take) includes a whole bunch of elevator pitches from screenwriters, who also use comp titles (“It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman”). They’re played for comedy and they’re funny but all of these pitches begin to feel stale, vacuous, uninspired. As we watch the output of popular book publishers grow ever more conformist under corporate consolidation, we need to find new ways to make (and to celebrate) what’s wonderful and weird.

Maris Kreizman

Maris Kreizman hosted the literary podcast, The Maris Review, for four years. Her essays and criticism have appeared in the New York Times, New York Magazine, The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Esquire, The New Republic, and more. Her essay collection, I Want to Burn This Place Down, is forthcoming from Ecco/HarperCollins.