It's okay, baby girl, here are 9 more literary daddies to clutch.

Having never played The Last of Us the video game, I envision HBO’s adaptation as, essentially, The Mandalorian with Lyanna Mormont in place of baby Yoda. There is something fundamentally heart-murmur-inducing about a man clad in literal or emotional armor melting on the inside as he cares for a child—a sublime softening of the male exterior. So rare is the literary man brought to his knees by care for another, so hard-won the love, it’s all the more moving when it is given.

Without spoiling anything, the first season of HBO’s The Last Of Us is a study in the formation of a father-child bond between Joel (Pedro Pascal, ya daddy) and Ellie (Bella Ramsey). By the time he finally clutches her to his apocalyptic shirt and growls, “It’s okay, baby girl, I got you” and Ellie clasps her little child hands around his neck, my maternal heart leapt clean out of the water.

As Phillip Maciak noted sensibly of the appeal of the Congressional Dads’ Caucus, “visible acts of dadliness are subject to a kind of social grade inflation,” and this is certainly true in literature. So, before we journey carelessly into the list of literary daddies, I want to note that not all dads are daddies, and not all daddies are dads. Also, we can still do better, men!

*

Colonel Brandon in Sense and Sensibility, by Jane Austen

The moment Colonel Brandon sees young Marianne playing the pianoforte and singing, we think: Eew, he is pretty old. Here’s Marianne: “He is old enough to be my father; and if he were ever animated enough to be in love, must have long outlived every sensation of the kind. It is too ridiculous!” Also, he is not great at reading Shakespeare.

But this is indeed a slow burn; the quiet pen of affections Brandon has for Marianne culminates in his tenderly carrying her home after she goes a-tromping toward Willoughby’s house in a storm. EXTREMELY DADDY.

Athos in The Three Musketeers, by Alexandre Dumas

Of course, a great novel of camaraderie, The Three Musketeers gives us excellent (platonic) daddy vibes between young D’Artagnan and the presumed leader of the crew, Athos, who fight, drink, and love together. Feel this: Pulling Athos from a cellar, “D’Artagnan threw himself on his neck and embraced him tenderly. He then tried to draw him from his moist abode, but to his surprise he perceived that Athos staggered.” (He’s drunk.) Lots to love here.

Seymour in A Perfect Day for Bananafish, by J.D. Salinger

The tragedy of A Perfect Day for Bananafish, beyond how terrible all the adults in a given Salinger story are, is the perfectly deft relationship between young Sybil and Seymour, the traumatized veteran who helps her catch waves on a bodyboard. Before the unfortunate end, Seymour has strong daddy qualities indeed. Please admire this playful exchange between adult and child:

He took away his fists and let his chin rest on the sand. “Sybil,” he said, “you’re looking fine. It’s good to see you. Tell me about yourself.” He reached in front of him and took both of Sybil’s ankles in his hands. “I’m Capricorn,” he said. “What are you?”

“Sharon Lipschutz said you let her sit on the piano seat with you,” Sybil said.

“Sharon Lipschutz said that?”

Kills me!

Phil Jackson in Sacred Hoops, by Phil Jackson

I haven’t yet bought a wooden Navajo eagle, but if I did, I wouldn’t be the first to go that way after reading Chicago Bulls coach Phil Jackson’s tale of overcoming himself. In the book, he recounts his failure to succeed at pro basketball, injury, and then a failed marriage and relocation to (gasp) Albany, NY. What makes it all so winning is his self-awareness (and of course his height). The egotist turned Buddhist will melt you, if you’re inclined to those sorts of things.

Rob Delaney in A Heart That Works, by Rob Delaney

Now we’re getting down to it. What if the essence of a literary daddy is his ability to grip a falling-apart world and tell you it is okay? In his memoir capturing the life and death of his third-born son, Delaney talks about the power of admitting the size of someone’s tragedy. He wants honesty, and it cleaves you in two: “I can offer you no consolation, my friend. Your disaster is irreparable. What do you intend to do?”

The narrator in A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself, by Peter Ho Davies

Here, the voice of a father-in-formation is the thing you will lust after the most. Peter Ho Davies’ autofiction novel about a couple’s miscarriage then pregnancy and child wins you over with its naked ability to witness our vulnerabilities as parents. The father is worried for the child, exists as a scaffold for child-centered hopes: “The judgement of the world. He feels it turning inexorably from himself to the boy, wishes he could shield him from it, fears he’s destined, like all parents, to only be the lens that focuses it.”

Boo Radley, in To Kill A Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

Atticus would be a bit of a gimme, the race-conscious public defender who bravely parents alone (well, with a housekeeper, to be fair), and so we focus here on low-key daddy and once-feared neighbor, Boo Radley, who leaves presents for the children in the tree and turns out, like The Beast, to be something more. When Jem is attacked by Bob Ewell, it is Boo who protects Scout, stabs the old racist, and carries Jem gently home.

Tamlin in A Court of Thorns and Roses, by Sarah J. Maas

Oh, I put him on the list! Tamlin is a reluctant High Lord and faerie with long blond hair. A human girl, Feyre, kills his friend while he is roaming the human realm as a wolf, and Tamlin takes her back to his castle. They hate each other at first! But the power balance shifts, and… there’s a reason people devour these books.

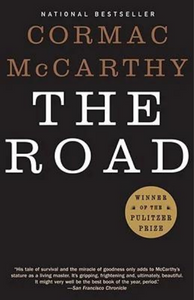

Man in The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

The most Joel-slash-Mandalorian of this list gets us back to the end of the world. May there be a strong set of hands and a voice brave enough to tell us: “You have my whole heart. You always did. You’re the best guy. You always were. If I’m not here you can still talk to me. You can talk to me and I’ll talk to you.”

As long as a dad remains, there is hope!

Janet Manley

Janet Manley is a contributing editor at Literary Hub, and a very serious mind indeed. Get her newsletter here.