The first time I kissed an Indian, it didn’t feel like incest, and I was surprised. Maybe it was because we had blurred ourselves with cheap white wine in anticipation of the event—but I can’t speak for him. Sure, I’m the product of two Indians—but one and two generations removed from the unpromised land, from dar-bath-shak-rotli in the kitchen every night. All the desis I knew were cousins or felt like it. Or they were like me and had a thing for blondes. I couldn’t blame them, really—it’s hard when you grow up here.

Well, sometimes I blamed them, my desi brothers; the very best-looking ones were always sure to have a tennis player on their arms or behind their parents’ backs. I scan the announcements to see if they are marrying these tennis players (and yes, some of them are). And what about me? The boys I go out with are scarecrows: working class Methodists or Episcopalians or rebellious trust fund WASPs. You’ve seen them around—they have an earnestness around the eyes, the nose like a kid drew it, a dog they love more than girls, the hope of teaching English in China someday.

Maybe I gave the Indian too much credit, because he didn’t try to tell me stories about women in Rajasthan, thinly quoting the last article in The New Yorker or the Times that had to do with the plight of women or the horror of arranged marriages (so fascinating!) or the sanctity of the hymen or the supposed dowry problem. Perhaps he was tired of having such stories quoted back to him from smart Jewish guys at work or well-read tennis players anywhere—(airports, bars, weddings, dates). Maybe I should be telling this story to him and not to you. I don’t mind if you listen, though. You: you could learn a thing or two.

Obviously he didn’t taste like saffron, like turmeric, like asafetida. He tasted—you tasted—like the inside of a wine bottle, the green neck of a wine bottle. Your lips were surprisingly soft. You clearly wanted to forget about an old girlfriend and came quickly, damply, into your corduroys. I was embarrassed for you. We were out on a terrace, and I wondered who could see us. If there was such a thing as privacy in India, I didn’t find it. If there is such a thing as divination, I misread it. We drank glass after glass and stayed outside though the insects hummed incessantly around our hands, our eyes, the rims of our smudged glasses. A near-empty carafe stared back at us. I thought: maybe this is the one.

Maybe I should try telling a more palatable story: about kissing a boy who had skin as brown as my brown skin, who worked in computers, who drank single malt with the guys from work, who listened to hip-hop, who wore a blue shirt the color of Friday casual, the color of desire. Maybe the problem is that I read the Times article. I thought we might fall in love, marry, have a story to tell our children. Listen kids: we met on the night train from Bangalore to Madras. Or: we met in Madras (now Chennai), but we first noticed each other on the night train. I pretended to sleep, to ignore the dosa-wallah, the coffee-wallah, the others on the wedding trip. I thought the coffee-wallah would return and he never did. How I wanted you to come to my row of seats and visit! And you did, after a time. Or maybe I should tell our children the truth: I had to come find you. You were talking to the girl with yellow hair, and I thought: this is it. You have found your perfect opposite. What could you possibly want with me?

What seduced me? Was it traveling with only one other desi on a trip of Americans and a handful of Europeans? It seemed that you were the only other Indian the way everyone nudged us together, left dinner early, pointed out your virtues, etc.—and of course you weren’t the only Indian—we were in the ancestral homeland after all. More of us than I’d ever seen. Our parents called this place home perhaps, or had once called it home; we had this small fact in common. And we shared this fact with six million people or one out of six people or something rather unremarkable—maybe only remarkable in its easy probability that two of six million might find themselves staring past a carafe into each other.

Was it that we were going to a wedding? Or that you lived in that mythical city, New York, and that I was the age to be looking for myths—or that you had that familiar deviated-septum desi nose—or that you were South Indian (Brahmin, Tamilian), but didn’t seem to hold it against me that I wasn’t? Is it too scripted to suppose that brown chases brown? That brown is divinely meant to come together with brown? Where is the divination? Was it too much to hope that a night train from Bangalore to Madras might yield a good story for our children?

I suppose our children are still out there, but have gone on to be born to other people. When I told you I lived in Ithaca, you told me you didn’t go further than Duchess County. (I thought probably you wouldn’t make it past White Plains. Why did I kid myself?) It seemed pretty clear. We traded three phone calls and talked once, on my coin. It was the last day of October and kids had long stopped ringing the doorbell. That was all.

Children: your mother’s mother traveled from Dar Es Salaam to Surat to meet her betrothed—on a boat that made her sick. She sailed a steam boat from one continent to another. Surely you understand why I can’t marry your father—for him, Ithaca is far. You wouldn’t like a father who cannot travel—who will not travel. How will we show you where you are from? Ithaca, Manhattan, Bangalore, Surat. I wasn’t quite honest before. All the desis haven’t felt like cousins. I’ll keep trying. I just want you to be able to get back to the unpromised land, when you need to, when this whiteness is too much with you.

Oldest son: How will I be able to force you to take Gujarati lessons if your father is American? Who will remind you to take your shoes off at the foot of the temple when I’m tired and your sister is in my arms? Perhaps it will be your father, (thin, holding your hand, I can see that much in my mind), who will drive you to your Gujarati lessons, who will be more fluent than myself, who will not mind trans-Atlantic flights nor applying for visitor visas. Perhaps he will keep track of the lunar calendar and will remind me of when the harvest festival and the New Year fall each year—there have been times I’ve not even forgotten, but just not known. There are times I haven’t been a good Indian. I have tried to be a good Hindu, to be your good mother. Each night, I unravel.

Forgive me, beta: I’m trying to make a good decision. I look for your dark lashed eyes, for your crooked smile, in each face, in every bar, in each set-up, trying to find your father, trying to recognize your laughter. How will I know if what you want is to be lighter, to be stronger—is to have a connection to Ireland? How will I know if what you are is half Jewish? My hand falters on the loom. First son: send me a sign, rent these fictions. What I’m wearing is red. What I’m looking for has already been written, what I can’t read splays itself across the sky, nightly.

__________________________________

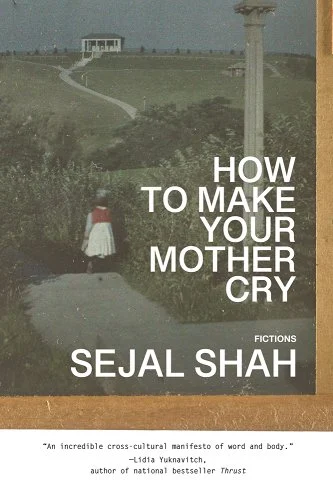

From How to Make Your Mother Cry. “Ithaca Is Never Far” first appeared in a special issue of / poetic supplement to Prairie Fire: A Canadian Magazine of New Writing called “Race Poetry, Eh?” (Vol. 21, No. 4). Used with permission of West Virginia University Press. Copyright © 2024