“It Will Be One of the Most Ghastly Short Stories Ever Written.” When Dylan Thomas Tried to Get Spooky

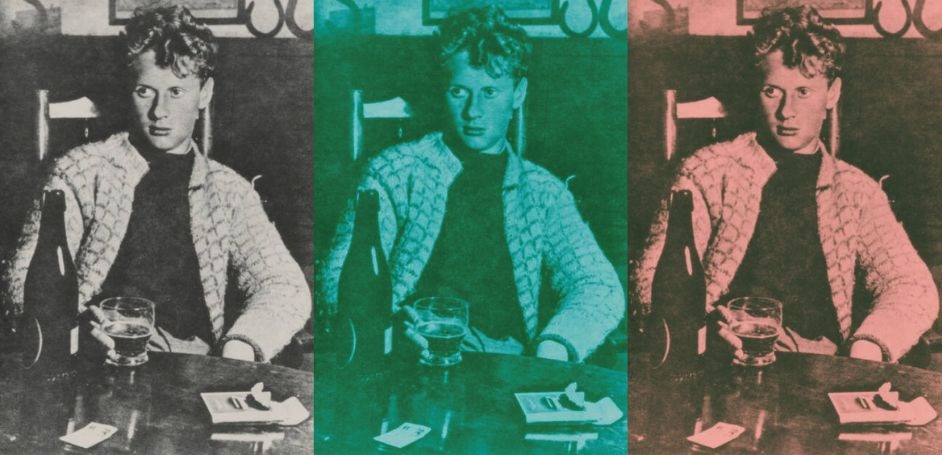

Nick Ripatrazone on the Great Poets Early Foray Into Darkness

Late in 1933, Dylan Thomas started writing a new short story. “The theme of the story I dreamed in a nightmare,” he wrote to a friend. “If successful, if the words fit to the thoughts, it will be one of the most ghastly short stories ever written.”

Thomas was possessed, in part, by rejection. The editor of The Adelphi, an English literary journal, had solicited some new poems—only to pass on them. “The poems have an unsubstantiality, a dream-like quality, which non-plussed me,” the editor wrote. Thomas, quite miffed, complained: “He accused me—not in quite so many words—of being in the grip of devils.”

Nineteen, and already prolific, Thomas was in the grip of something, and dashed away his drafts in a red notebook. The Zenith Exercise Book, a school journal, came with warnings for children on its back cover, including: “Don’t follow a rolling ball into the road or street while there is traffic about!” Thomas’s imagination thrived between the covers.

The story he was working on was titled “The Tree.” Although the story has faded among his oeuvre, it is a masterful work of horror: a window into a young writer’s entrancing vision.

On Christmas Day, 1933, Thomas was jocular as ever. “How many more Christmases will these old eyes be blessed to see approach and vanish,” he wondered. “Who knows: one far-off day I may gather my children (though a resolution denies it) around my spavined knee, tickle their chops, and tell them of the miracle of Christ and the devastating effect of too many nuts upon a young stomach.” His uncle had given him the collected letters of William Blake, and Thomas was mystified by the poet’s voice, from his sentences on down to his salutations: “Dear leader of my angels,” “Dear sculptor of eternity.”

“I am filled with the terror which is the beginning of love. They tell me space is endless and space curves. And I understand.”

Perhaps settled into the melancholy of a long holiday’s evening, Thomas wrote another letter. “A chunk of stone is as interesting as a cathedral, or even more interesting, for it is the cathedral in essence; it gave substance to the building of the cathedral and meaning to the meaning of the cathedral, for stones are sermons, as are all things,” he mused. He was quietly hopeful for himself; for his art. He longed to believe “in the magic of this burning and bewildering universe, in the meaning and the power of symbols, in the miracle of myself & of all mortals, in the divinity that is so near us and so longing to be nearer, in the staggering, bloody, starry wonder of the sky I can see above and the sky I can think of below.”

The Adelphi editor, when rejecting his poems, had noted that they seemed to have been written in a trance. In his letters, Thomas seems to have embraced such Yeatsian somnambulation: “When I learn that the stars I see may be but the backs of the stars I see there, I am filled with the terror which is the beginning of love. They tell me space is endless and space curves. And I understand.”

In the days that followed, Thomas continued his “nightmare” story, completing it on December 28th. “The Tree” would appear the following December in The Adelphi, which had apparently warmed to disturbing art.

“Rising from the house that faced the Jarvis hills in the long distance, there was a tower for the day-birds to build in and for the owls to fly around at night,” the story begins. A child is transfixed by that tower. He “knew the house from roof to cellar; he knew the irregular lawns and the gardener’s shed where flowers burst out of their jars; but he could not find the key that opened the door of the tower.”

The gardener tends to the boy’s imagination. The man “knew every story from the beginning of the world.” Yet his favorite source was the Bible: “When the sun sank and the garden was full of people, he would sit with a candle in his shed, reading of the first love and the legend of apples and serpents. But the death of Christ on a tree he loved most.” The gardener often speaks to the boy of Christ’s crucifixion.

“The Tree”—written by a teenage Thomas—captures the miraculous imagination of youth, when fantasy is fulfilled, where myth is unbridled truth. Thomas’s prose is gorgeous: “To the east stood the Jarvis hills, hiding the sun, their trees drawing up the moon out of the grass.” His lyricism conjures horror. The boy, unable to sleep, follows shadows down the stairs, leading him outside onto the grass, and finally toward the titular tree. “The child touched the tree; it bent to his touch,” Thomas writes. “The child had not doubted the tree. He said his prayers to it, with knees bent on the blackened twigs the night wind fetched to the ground.” He longs to enter the tower.

Thomas begins to unfold a parallel story; a gentle man “who walked the land like a beggar.” He was given a suit that “lopped round his hungry ribs and shoulders and waved in the wind as he shambled over the fields.” A mysterious voice in the distance compels the man forward to the Jarvis hills. “Bethlehem,” he says upon reaching there, “turning over the sounds of the word and giving it all the glory of the Welsh morning.”

It is soon Christmas Eve. The gardener, with his “long, thick beard, unstained and white as fleece” whom the boy thinks is an “apostle,” has an early gift. The gardener unlocks the tower, and the boy enters the room. It is empty. “Where are the secrets?”

The boy weeps. He paces the empty, dusty room. He looks out the window and through the falling snow, and he sees a “world of hills” that

stretched far away into the measured sky, and the tops of hills he had never seen climbed up to meet the falling flakes. Woods and rocks, wide seas of barren land, and a new tide of mountain sky sweeping through the black beeches, lay before him. To the east were the outlines of nameless hill creatures and a den of trees.

The tower’s secret was sight. “That night,” Thomas writes, “the child slept well; there was power in snow and darkness; there was unalterable music in the silence of the stars: there was a silence in the hurrying wind. And Bethlehem had been nearer than he expected.”

On Christmas morning, the wanderer arrives. Tired, he rests against the tree, but soon becomes afraid as he stares up at the tower. His hands make the shape of prayer as “a fear of the garden came over him, the shrubs were his enemies, and the trees that made an avenue down to the gate lifted their arms in horror.”

The boy finds the man, who “has fires in his eyes, the flesh of his neck under the gathered coat was bare.” They speak. When the man says that he has come from the Jarvis hills, the boy takes that as a sign. He tells the man to stand up against the tree and put out his arms. Then, the boy ran to the gardener’s shed to fetch wire. When he returned, the man still stood against that ancient tree, “straight and smiling.”

“Let me tie your hands,” the boy said.

Dylan Thomas once described God as “the author, the milky-way farmer, the first cause, architect, lamp-lighter, quintessence, the beginning Word, the anthropomorphic bowler-out and black-baller, the stuff of all men, scapegoat, martyr, maker, woe-bearer.” At nineteen, suffused with Blake’s mysticism and something devilish, he wrote a horror story during Christmas. We will never know the exact mixture of the alchemy, but “The Tree” is a staggering myth.

The boy wrapped the wire around the man’s wrists; “it cut into the flesh, and the blood from the cuts fell shining on the tree.”

“Brother,” the man says, leading to the story’s final line of the coming crucifixion: “He saw that the child held silver nails in the palm of his hand.”

Nick Ripatrazone

Nick Ripatrazone is the culture editor at Image Journal, and a regular contributor to Lit Hub. He has written for Rolling Stone, Slate, GQ, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, and Esquire. His most recent book is The Habit of Poetry (2023). He lives in New Jersey with his wife and twin daughters.