“It Is Not a Given”: Marcie Bianco Lays Out the Steps to Reclaiming Freedom for Feminism

On Self-Creation, Mutual Relationships, and the Importance of Rest

Step one to reclaiming freedom for feminism: Claim it.

Unlike with equality, we do not need to wait for men or their patriarchal institutions to patronizingly bestow us with freedom (and then send out dozens of press releases celebrating their beneficence). Freedom is not given. It is claimed. We have the power to choose it. We are not subject to men’s impulses, nor do we have to petition them to lay claim to it.

But to be clear, freedom is not a thing that is claimed like a material possession. Rather, when I say we must claim our freedom, I mean we must affirm it. As an ideal, freedom is no more abstract than equality but is far more achievable because it is a continuous practice that begins within us. Whereas equality is imposed externally by institutions, in the form of rights and protections, freedom is a felt and shared experience created through our active doing. Therefore, it is claimed—actualized—in practice. We can express our freedom daily in how we choose to live our lives and by engaging with the world in a way that acknowledges and respects the dignity and freedom of all people.

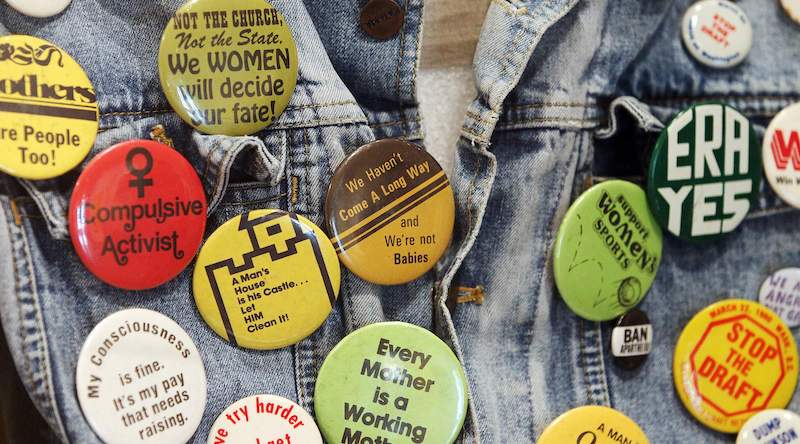

Step two: Take back freedom from the white supremacist patriarchy. We can begin this effort by learning from and building upon the decades of Black, radical, lesbian, and freedom-centered feminists whose ideas and activism have shown us that freedom is not realized through the domination and oppression of others but through mutual relationships. Collective freedom depends on our mutual freedom.

Freedom is a lifelong practice of self-creation based in accountability and care and that endeavors to build a freer and more just world.

To level-set and define these terms: Self-creation is inspired by Black feminists like Patricia Hill Collins, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde who have theorized the importance of “self-determination” as a direct response to Black women’s long-denied human dignity and bodily autonomy. “Black self-determination,” hooks wrote in Killing Rage: Ending Racism, is how “African Americans, across class, create radical liberatory subjectivity even as we continue to live within a white supremacist capitalist patriarchal society.” This creation is a collective process, she explained, “by which we learn to radicalize our thinking and habits of being in ways that enhance the quality of our lives despite racist domination” so that “we live lives of sustained well-being.” The effort to determine oneself is nothing short of a willed survival for oneself as well as for one’s community. As Lorde said in “Learning from the 60s,” “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

Self-creation is a version of self-determination that elevates aesthetics as a constitutive element of our becoming, of how we design and give meaning to our lives. The process centers creativity as a driving force in manifesting our authenticity and imbuing our life with meaning.

Accountability is the deliberate choice to take responsibility for our choices and actions as well as for their impact. The significance of accountability is that it is an ethic that precedes and informs our actions, and it also compels us to ensure and increase the freedom of others by, for instance, taking action to repair harm when harm is done. Accountability is the lynchpin of freedom because it indicates how freedom is both relational and conditional. Care is not just about repair, restoration, preservation, and survival. A feminist ethic of care is much more expansive and includes our mutual pleasure, thriving, and satisfaction. Touch is care. Love is care. Sex is care.

Burning ourselves out and burning up the Earth so that a handful of women can become rich and powerful is not feminism. We don’t seek a seat at the table. In fact, we don’t want to even use the table that men built.

A feminist freedom, therefore, is realized in how we intentionally design our lives with other people. Our lives are codesigned, cocreated. Self-creation is world-building—which is another way to interpret the famous feminist mantra that the personal is political. Because if we choose to center freedom and live by its values—dignity, authenticity, mutuality, justice, accountability, and care—we not only can liberate ourselves from oppressive systems but also can revolutionize those very systems. This includes liberation from the patriarchal gender binary and reductive identity politics. I agree with Linda Zerilli that “a freedom-centered feminism is concerned not with knowing (that there are women) as such, but with doing—with transforming, world-building, beginning anew.” Our identities do not and should not prevent us from doing the work of freeing other people—which, according to Toni Morrison, is the very function of freedom.

With my definition, I engage with, honor, and build upon the decades of work by feminists who have fought for freedom, including Barbara Smith, who in a 1979 lecture said:

Feminism is the political theory and practice that struggles to free all women: women of color, working-class women, poor women, disabled women, lesbians, old women—as well as white, economically privileged, heterosexual women. Anything less than this vision of total freedom is not feminism, but merely female self-aggrandizement.

Freedom is fundamentally a collective endeavor. The horizon of my freedom is not limited by yours but broadened by it. And feminists must challenge any rhetoric about freedom that suggests otherwise.

Whereas equality feminism measures its ultimate success in its obsolescence, freedom feminism maintains an opposite teleology, guided by the belief that freedom is not a one-time event or achievement but a commitment to live deliberately and with the intention to realize and affirm our freedom and the freedom of others. Because, as the steady chipping away of voting rights and the Dobbs decision have shown us, no right is guaranteed. The fight for freedom is not one and done—or, in the context of rights, won and done. It is enduring, and it must endure if we are to ever upend the stranglehold of the white supremacist patriarchy.

We can only surpass the current conditions of our lives through our relationships with people—those who raise us, teach us, mentor us, support us, inspire us, and love us, and whom we raise, teach, mentor, support, inspire, and love in turn. This is how my freedom is connected to your freedom. Freedom does not exist—it cannot be felt or experienced—in a silo.

Step three: Practice, practice, practice. Freedom is expressed and felt in action. Only through practice can we engender a culture that affirms a feminist understanding of freedom. The collective impact of this daily practice can produce societal change through rewriting the scripts about freedom and American values. A feminist politics can emerge that is not based on identities or the gender binary but in efforts to realize freedom for all—to secure and respect everyone’s human dignity, to provide care specific to need, and to advocate for justice for all, no matter identity, no matter citizenship status. What is considered a feminist “victory,” then, is no longer measured by profit or having what men have. Burning ourselves out and burning up the Earth so that a handful of women can become rich and powerful is not feminism. We don’t seek a seat at the table. In fact, we don’t want to even use the table that men built. Success, rather, if it is even the right word, is measured in terms of the collective well-being—the public good, public health (including housing), public education, and environmental health (biodiversity and ecosystems).

Freedom practice can be visualized as a continuous, enfolding relationship comprising internal work and external action. Our mindset and beliefs inform our actions, and our actions—and their effects—also inform our mindset and beliefs. We generally understand this process in terms of learning from experience over time. Of “not making that mistake again.” The ongoing internal work also indicates that our actions should always be thoughtful, not thoughtless, and that we should lead with intention, care, and consideration for how our actions affect people we know and don’t know, all species, and the Earth itself.

The internal work of freedom liberates us from the equality mindset. The cognitive process of breaking free from old ways of thinking and patriarchal conditioning entails an awakening that liberates the mind, producing an awareness of oneself and one’s place in the world. From this awakening and awareness, one can develop a critical consciousness, which inspires the choice of accountability as an ethic that shapes one’s actions to create a more free, caring, and just society.

for our collective survival—and for the survival of this planet and all its life-forms—we must dismantle white freedom’s cultural dominance, break down the logic of its parts and reveal its motivations.

The internal process of developing a critical consciousness also reveals how our lives are interconnected and interdependent, proving how my freedom is made possible by your freedom, and vice versa. The very fact that we exist in a world with multiple ecosystems and depend on those ecosystems for the continuation of our existence proves our interdependence and justifies a philosophy of freedom based on it. Beauvoir used the term intersubjectivity to describe how it is through our mutual recognition of each other’s human dignity that freedom is possible.

Fundamental to this internal work is rest. The Nap Ministry founder Tricia Hersey explained that “rest is resistance” to white supremacy, capitalism, and the patriarchy because it provides us the dream space to imagine liberated futures and heal from systemic harm. Dreaming is powerful, Hersey noted in Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto, because it disrupts the capitalist grind culture that demands we treat our bodies and each other like machines: “Dreaming is the way we move toward liberation because it is a direct disturbance to the collective reality of life under capitalism. Grind culture is violence.” And the consequential exhaustion, burnout, and isolation are not coincidental. They leave us depleted and alone, without the energy to imagine better, freer, and more caring ways to be in this world. We become disengaged, dispassionate, and even disembodied, zombie-like people. And who hasn’t felt this way? I certainly did trying to write this book while holding down a demanding full-time job. There were days and weeks when I was just tapped out, without an idea, and without the creative reserves to write one word. Creativity, as I have experienced it, is sparked by engagement with the world—with friends, in group activities, and at events like book clubs and lectures, as well as by reading (which allows the reader to textually engage with the ideas of others, even those who may no longer be alive). But grind culture and, correlatively, the “having it all” of equality feminism, prevent such creativity from happening. The work of freedom demands that we rest, that we give our bodies the time to feel and think through—and even let go of—experiences so we can learn from them.

The internal work and external practice of freedom are mutually constitutive. We can think of freedom, therefore, as an ethics—a set of practices cultivated through our encounters and experiences intended to express our values. Integrity and authenticity come from living our values. And the final trio of chapters in this book explore this freedom work via an examination of the three most critical spheres of women’s liberation from both the patriarchy and the equality mindset: the mind, the body, and movement.

The feminists—and specifically the Black feminists—who have done this freedom work not only knew that dignity, self-determination, and justice were impossible within the politics of equality feminism, they knew equality wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t real. It wasn’t experienced. And their ideas resonated with me, because I have always craved the freedom to become my own person, to move freely, to think freely. That freedom, however momentary, has always made me feel powerful. Made me feel real, and really seen. And while I could intuit this truth about freedom from an early age, it was only by studying these feminists that I understood that freedom is about more than personal experience. It is about all of us, and, guided by freedom, we have the potential to liberate and lift up everyone—not just those who are already at the top—without losing sight of ourselves and the differences that make us who we are.

The fight for freedom, too, is about more than just feminism. It is about the future of this country. The conflicting philosophies of freedom—the white supremacy masquerading as freedom and the feminist freedom I offer here—represent the tensions at play in America’s culture wars. Yet, for our collective survival—and for the survival of this planet and all its life-forms (because if there is no Earth, no oxygen for your mortal body to stay alive, you can’t abscond to your metaverse)—we must dismantle white freedom’s cultural dominance, break down the logic of its parts and reveal its motivations.

It is time for feminists to reclaim freedom from the white supremacist cis-heteropatriarchy, reassert its true definition, and take control of the narratives that shape our lives and our society.

_________________________

Excerpted from Breaking Free: The Lie of Equality and the Feminist Fight for Freedom by Marcie Bianco. Copyright © 2023. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Marcie Bianco

Marcie Bianco is a writer, editor, and cultural critic. She has written, taught, and lectured about feminism, ethics, literature, and culture for more than fifteen years. A 2013 Lambda Literary Fellow, her writing has appeared at CNN, NBC Think, and Vanity Fair, among other outlets and academic publications. Bianco is a columnist at the Women’s Media Center and a SheSource expert. She currently is an editor at Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIR), an award-winning quarterly print magazine.