It Happened To Me: On Being Totally Unproductive at a Writing Residency

Alice Robb Realizes That Solitude Isn’t For Everyone

I drooled over the photos on the residency’s website: writing studios that looked like treehouses. Acres of forest dotted by wildflowers and waterfalls. Chef-prepared vegetarian meals. When I got my acceptance letter—and began preparing to spend two weeks in the woods of rural Georgia, in a cabin with no cell phone service or Internet connection—I imagined that I would enter a fugue state and write thousands of words a day. I imagined that I would revamp my entire writing routine. That I’d discover that I was not a slow writer, as I’d always thought—just a Twitter addict.

From what I’d gathered, residencies were mythical places where a writer could befriend famous artists and unlock new levels of creativity. In Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer, the narrator describes the fictional Quahsay Colony—presumably based on Yaddo, which Roth attended seven times—as “a marvelous, a miraculous gift”: “I loved the serenity and beauty of the place… I loved walking the trails there at the end of the day and reading in my room at night.”

In Ben Lerner’s 10:04, the Lerner-esque narrator becomes glamorously unhinged at a writers’ colony in Marfa, Texas–reading Walt Whitman all night, strolling through the deserted town at dawn and going to bed at sunrise. He stops shaving, declines social invitations and whittles his needs down to a single, midnight burrito. Coming untethered from society fuels his creativity: he emerges from his solitude with a strange, metaphysical poem about “an alien with a residency.”

Another of my favorite novels, Rachel Cusk’s Kudos, features a novelist for whom an Italian castle becomes the site of a long-awaited breakthrough: thanks to a writing prompt suggested by a fellow resident, she finally finds the key to a story that’s been stumping her, and sells it to the New Yorker.

So I felt smug as I set up my vacation reply—“I am at an artists’ colony with limited access to the Internet.” I imagined the envy it would incite in my desk-bound friends in New York as I packed a stack of books for research, another stack for pleasure, some emergency protein bars, and flew down to Georgia.

I imagined that I would enter a fugue state and write thousands of words a day. I imagined that I would revamp my entire writing routine.

I arrived to find my cabin as cozy as the one in the brochure. “Everything I need to finish my book,” I thought contentedly, as I took it all in: exposed wood beams, a vase of wildflowers on the desk, even a piano in the corner. Best of all were the floor to ceiling windows, through which I could see only foliage and sky. I flipped through the cloth-bound guestbook that lay open on the desk, skimming messages of encouragement from painters, poets and sculptors.

On the night table was an old-fashioned landline phone, which, I had been warned, didn’t work for outgoing calls; if I wanted to talk to friends or family back home, I would have to hike to the main house, ask them to call me in eight minutes, and hurry back. I flicked on the reading lamp beside the chaise longue: this is where I would relax in the evenings after I’d met my daily quota of—two thousand words? Three? I hadn’t decided yet, but I could already feel my satisfied exhaustion after a hard day’s work, the mental version of apres-ski.

That night, it rained. At home, I love the sound of a good storm: I sometimes fall asleep to a YouTube video called “Heavy Downpour & Massive Thunder.” But, alone in the woods, I did not find the sounds of heavy downpour and massive thunder soothing. I wondered what danger they could be masking. What did bears sound like? I wished I could google it. I wished I had listened more closely at orientation. I wished I could turn on a comedy show or a podcast—anything to confirm there was a reality outside this room. I missed my dog.

I woke the next morning feeling ragged but also relieved: the sun was up, the house no longer haunted. In the daylight, the mountains weren’t menacing—they were beautiful. I set the kettle on to boil and sat down at my desk. Out of habit, I opened a web browser and typed in NYTimes.com. You are not connected to the Internet. Of course.

I pulled up the document with my half-finished book and read a few sentences. But I couldn’t focus: I wondered if anyone had texted me overnight. I considered hiking down to the WiFi zone, then scolded myself. I had come all this way to write without distraction. I returned to the document, trying to reorient myself, but before I could, the kettle hissed.

Five minutes later, I was back at the desk, mug of coffee in hand. I reread the same sentences. Were they any good? I looked out the window. I looked back at the screen. I wondered if anyone had texted me.

And so passed the hours, and the days. I counted the (unchanging) number of words I still had to write and divided it by the number of days until my deadline. I divided it by the number of days until my deadline, minus weekends. I made cups of tea. I looked out the window and thought about the fact that I would one day die.

I left not with the finished chapters I had hoped for, but with the knowledge that writing is—at least for me—a social act.

When I discovered a few episodes of Bachelor in Paradise saved on my computer—the signal at the main house was too weak to download new videos—I had never been so grateful for the sound of human voices, even if those voices belonged to twenty-four-year-olds deciding whether to get engaged after knowing each other for a few days.

At seven each evening, the other residents and I would emerge from our far-flung studios and gather at the main house for dinner. Due to Covid protocols, we sat at a long, banquet-like table on a covered porch, each six feet away from the next, before retreating to our individual cabins.

To be clear: the residency’s organizers were lovely; the other artists, collegial; the food, restaurant-worthy; the scenery, picturesque. And yet, it was one of the least productive two-week stretches I’ve ever had.

But it wasn’t a waste. I left not with the finished chapters I had hoped for, but with the knowledge that writing is—at least for me—a social act; that creative thinking happens not in isolation but in the in-between.

I shouldn’t have needed to go all the way to Georgia to learn this. As a kid, I learned to do my homework backstage at the Nutcracker, amid the chaos of dancers stretching and chatting while the orchestra played upstairs. At home, my favorite place to study was at the kitchen table, where I was liable to be interrupted every few minutes.

At night, when I retreated to my bedroom, I fought the silence by blasting music through my headphones. In college, I rarely worked in my dorm room; I preferred to lug all my books to the library and install myself at the long, communal table closest to the entrance.

As I write this now, I am also listening to Lucinda Williams on Spotify, texting my boyfriend about the sandwich I ate for lunch and thinking about whether to walk or take the subway to dinner tonight. Behind this google doc are tabs in which I’ve searched “synonyms for creativity” and “the cast of Nine Perfect Strangers.” I’m thinking about what I’ll wear to the ballet tomorrow and I’m trying to write as many words as I can before dinner—I’ve decided I’ll walk.

I’m having a great time.

_____________________________

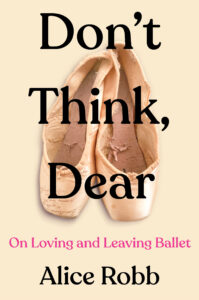

Don’t Think, Dear by Alice Robb is available from Mariner

Alice Robb

Alice Robb has written for Vanity Fair, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and The New Republic, among other publications. Her first book, Why We Dream was recommended by The New Yorker, The New York Times, Today, Vogue, TIME and The Guardian, and has been translated into seventeen languages.