The first time I slept with my future husband was in a beach house an hour north of my childhood home. My boyfriend had been given the keys to it for the weekend by its owner, Camilla, a retiree he’d worked for in the New Zealand government. The house was a modest rectangular modernist box, raised off the lawn, wood paneled inside, except for floor-to-ceiling windows at the front with a wide view of the coastal sky. Neither the building nor its contents seemed to have been updated since the sixties, and the atmosphere inside was super cozy. A pair of recliners upholstered in nubby beige angled toward each other in the lounge, around a low table crying out for matching teacups and scones fresh from the oven. When my boyfriend mentioned that Camilla’s sister was often at the house with her, I instantly saw them sitting there, two old maids in cardigans and sensible shoes, tut-tutting over the papers and arguing over who’d pick up the cold cuts for their afternoon guests.

My boyfriend and I had only just started dating, but he was handsome, smart, and kind, and I was optimistic about our future together. I was also, technically, still a virgin and knew I was likely to rectify that within the next half hour. As I moved through Camilla’s house, I should have been consumed with excitement, capable of attending to nothing but our two young bodies and what we were about to do with them. Instead, a different thought was forming in my mind. It reached its climax as I laid my valise in the sunny bedroom, where my childhood would soon officially end. Omg—my chest thrummed—what if Julia and I bought this place when we retired and lived here together till we died?

I earned my adult badge, had a nice weekend, and told Julia about my vision as soon as I got back down the coast. She signed up for it instantly, as I knew she would. Whenever bad shit happened in the years to follow, one of us was likely to sigh, “Won’t it be so relaxing when we’re living at Camilla’s?” Car accident, dislocated foot, rejected manuscript, extramarital infatuation—to cheer us both up, I’d remind Julia of the comfy chairs overlooking the sloping lawn, how the late-afternoon sun sent a gentle glow round the room, what a perfect place it would be for knitting and reading, while our baking rose contentedly in the oven and our aged ankles swelled companionably in our slippers. After Julia got pregnant, we imagined her fetus arriving to deliver us groceries, introduce us to its partner, and clip the backyard roses with its fully developed hands. Our husbands were trickier to manage: it was hard to envision them on-site. But they were a decade older than us, and male life expectancy is lower. We were hoping, I guess, that they’d be dead.

*

Later, in the midst of my divorce, I began to see all of this as not having been a super-great omen for my marriage. When dragging boxes from the conjugal home to my car, for transportation to my sad little rental across town, or when exchanging crippling glances with my soon-to-be ex-husband in the offices of therapists or lawyers, I’d sometimes think of my blissful vision of twin retirement at Camilla’s with a more critical eye. “Jesus, Lena,” I recall puffing to myself once midstairs, while re-homing my half of the liquor cabinet, “what was that about?”

One thing Camilla’s offered to my younger self was a reassuring existential guarantee. Even if this new kind of intimacy with my boyfriend didn’t work out, I was likely telling myself, with more prescience than I knew, I’d always have a backup in place: a permanent home by Julia’s side. The idea that twinship provides a uniquely secure solution to loneliness and alienation is probably the biggest attraction of being a twin, for twins and singletons alike. One woman in a collection of photos of twins, Judy, reports, “Even if you’re unsure of God, you do know that, because of your twin, you are never alone.”

On first reading this, I wanted to say, “Judy, that’s so schmaltzy!” But I have to admit I’ve experienced a similar feeling, and I’m not sure what my emotional life would be without it. (How do singletons live?) I can count on Julia to want to hang out with me, but the reassurance she provides goes beyond that. Some part of me seems to believe that the mere fact of Julia validates my existence. She makes me feel my membership status in the universe is active, as if I’ve already passed some crucial cosmic test and every later qualification is optional. Just thinking of her calms me down, the way I imagine the thought of God, Gaia, or eternal flux does for believers, mystics, and Buddhists.

Alongside that, Camilla’s represented, maybe, a return. Julia and I began our lives together in the snug, dimly lit, twentieth-century lounge of our mother’s womb. Wouldn’t it be perfect, I imagine my younger self thinking, wouldn’t it just be right, for us to end up that way, once all the stressful subplots of life had played themselves out?

“Even if you’re unsure of God, you do know that, because of your twin, you are never alone.”Though I didn’t know it that weekend at the beach, this conception of the ideal relationship as a reunion of two parts once sundered has a long history in Western culture. It appears most famously in the creation myth told by Socrates’s fellow dinner guest Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium. We humans were originally egg shaped, Aristophanes says, with two faces, four legs, and four arms, which allowed us to tumble head over heels at speed. It was great for a while, but made us too powerful and arrogant for the gods’ tastes, so Zeus split us neatly in two. Ever since, we’ve felt existentially bereft and have yearned unhappily for reunion with our other half. We can never fully manage it, but we can come pretty close if we’re lucky enough to relocate our primitive soulmate, somewhere out there on the planet, equally lonely and yearning for our embrace. “And when a person meets the half that is his very own…then something wonderful happens,” writes Plato, “the two are struck from their senses by love, by a sense of belonging to one another, and by desire, and they don’t want to be separated from one another, not even for a moment.”

The idea of ideal love as a terrestrial twin was driven underground by Christianity—human hearts were meant to find their rest in God—but resurfaced and reached its peak in nineteenth-century Romanticism. Shelley described a couple in love as “one soul of interwoven flame,” and in Wuthering Heights Cathy exclaims to her nanny, “Surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you…Nelly, I am Heathcliff!” The core features of our contemporary ideal of romantic love were born in this period: the ideas that love between romantic partners, at its truest and best, is unconditional, selfless, and eternal, a haven of peace, a source of ultimate meaning, a guarantee of perfect happiness, and a redemption of all life’s sufferings. If romance subs for God in each of these ways, it also promises us the closest thing to immortality we skeptics can now hope for, by extending each lover beyond the bounds of their own mortal frame. “What were the use of my creation,” Cathy asks, “if I were entirely contained here?”

Seen against this backdrop, my vision of a beatific twin reunion at Camilla’s seems distinctively Romantic, while at the same being very unromantic, as far as my future ex-husband was concerned. This reflects a broader problem with the relationship between twinship and romance, which is an awkward fit by any measure. Twins clearly function as metaphors for singleton romantic relationships in the Platonic myth, and as Alice Dreger points out, many a love song can be read as a covert analogy to conjoined twins. (“I’ve got you under my skin,” Sinatra croons to his lover. But even Plato makes his myth’s uneasy fit with singleton romance quite clear. Our reunited ancestors “cannot say what it is they want from one another,” his mouthpiece, Aristophanes, states. “No one would think it is the intimacy of sex—that mere sex is the reason each lover takes so great and deep a joy in being with the other. It’s obvious that the soul of every lover longs for something else.”

Aristophanes suggests romantic lovers yearn to fit together not merely sexually, but in a more thorough-going and permanent way, like two lifelong halves of an apple. They want what’s impossible for them, we might say: to be actual twins. Identical twins, at least, literally come into the world as the result of asexual reproductive division, just like Aristophanes’s split ovoid creatures, or Eve, created from Adam’s rib in the Garden of Eden. Spend more than a little time thinking about that, and it starts to seem that we identicals don’t so much animate the Romantic ideal for singletons, as underscore the impossibility of their ever truly attaining it.

*

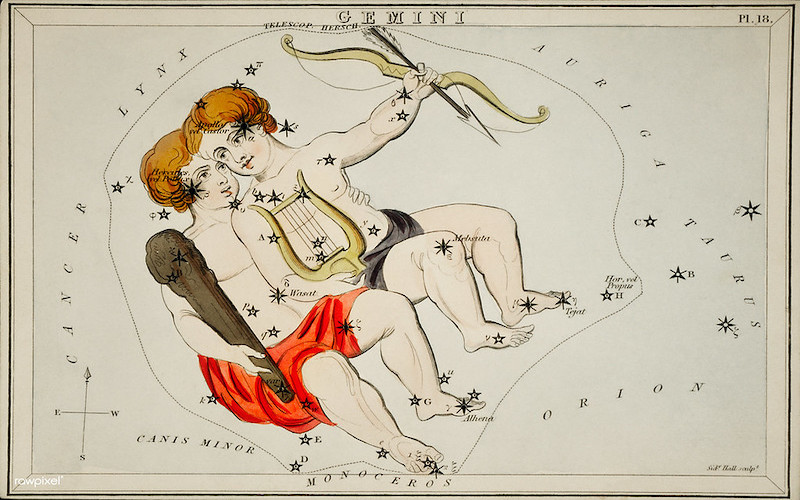

In Western culture, the myth of twinship—actual twinship—as the ideal human relationship takes its most famous form in the story of Castor and Pollux. The two were said to have resulted from their mother sleeping with Tyndareus, the king of Sparta, and Zeus, the ruler of Olympus, one after the other, resulting in one ordinary human baby and one touched by divinity, delivered at the same time. As the story goes, Castor and Pollux grew up to be the best of friends and spent all their time with each other, wearing their matching pointed felt caps, said to represent the vestiges of the two eggs from which they’d hatched. They were excellent horsemen and also loved hunting, sailing, boxing, and merrily picking fights with their rivals. Eventually, though, the fun ran out when Castor was mortally wounded in a brawl. As Castor lay dying, Zeus informed semidivine Pollux that he could give half his immortality to his brother, which would mean sharing half of Castor’s death. The details of the offer are fuzzy: in some tellings, the twins would live on alternate days forever; in others they’d winter together in Hades and summer on Olympus.

Are You Two in Love? Illustration by Julia de Bres

Are You Two in Love? Illustration by Julia de Bres

According to the ancient Greek poet Pindar, Pollux “didn’t give it a second thought.” In a choice between immortality and Castor, he went with Castor—of course. He likely felt about it the way Cathy felt about Heathcliff when she said, “If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger: I should not seem a part of it.” Deathless though he was, Pollux couldn’t live without his twin.

When I talk about my relationship with Julia, I find myself speaking in phrases sapped of force by centuries of overuse by singleton romantics. What does it feel like? people want to know. It feels like she’s always there for me, I say. I can never get enough of her company. We have more fun together than we have with anyone else. We understand each other better than everyone. We can tell each other everything. We trust each other completely. We’d do anything for each other. I make myself sick. But now and then the violent truth underlying these clichés surfaces, giant and graceless, like a whale. I was speaking about Julia a few years ago to a minor acquaintance at a bar when I heard myself say casually, one sip into a martini, “If I betrayed her, I couldn’t live.” I blinked and returned to my drink, self-startled. It wasn’t a thought I’d explicitly entertained before, let alone articulated to a semi-stranger. Like Pollux, I recognized it instantly as the basic fact of my life.

__________________________________

Excerpted from How to be Multiple: The Philosophy of Twins by Helena de Bres. Copyright (c) 2023 Helena de Bres. Used by arrangement with the Publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing. Illustration (c) 2023 Julia de Bres All rights reserved.