Is the Literary Biopic the Worst Kind of Movie?

On The Man Who Invented Christmas, and Watching Writers Toil on Screen

Very, very few things imperil my marriage quite as much as my inexplicable fondness for author biopics. It is to the stated, even irate bafflement of my counterpart-by-matrimony that I insist on indulging in the hopeless, brain-bangingly sub-mental, always-disappointing glut of movies like Trumbo, Kill Your Darlings, Shakespeare in Love, Sylvia, and perhaps the apex of the formula’s rank self-regard, the John Keats biopic Bright Star, a movie that would be infinitely better were its subject a talentless nobody lost to history rather than the larky and short-lived author of “Ode to Melancholy.” 2015’s In the Heart of the Sea, about young Herman Melville learning the story of the real Moby-Dick, is in another category altogether, both in terms of its preciousness and the violence it does its source material.

Ben Whishaw as John Keats in Bright Star (L) and Herman Melville in In the Heart of the Sea (R).

Ben Whishaw as John Keats in Bright Star (L) and Herman Melville in In the Heart of the Sea (R).

Writers actually have a pretty strong showing in motion pictures, in gruesome contrast to their reviled, nigh-invisible status in the broader culture itself. Do films like Midnight in Paris and The Trials of Oscar Wilde exist solely for aspiring writers to console themselves with? If so, it isn’t working—and it doesn’t matter. Because I love the sentient typewriters of Naked Lunch, the boozesome seersucker drawl of Capote, the quills of Quills (the quill-count in all of these movies being quite high overall), and maybe even Nicole Kidman’s Virginia Woolf prosthetic nose in The Hours regardless.

I know my esteemed paramour is right, of course: There’s nothing to be gained from watching actors with makeup on their faces stab sheets of paper, reliving a romantic and unreachable past, whimsical outsiders who attain in death the redemption denied them in life (“You see, Julie Christie? J.M. Barrie is not a danger to your children, he is just the boy-prince of fairy land!”) Even the best, like Mishima, tell me nothing about either Yukio Mishima, the man or the writer, and it’s for good reason that Lawrence of Arabia doesn’t include long scenes of T.E. Lawrence drafting The Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

“Do films like Midnight in Paris and The Trials of Oscar Wilde exist solely for aspiring writers to console themselves with?”

Typically the conflict in all of these movies concerns a starveling dearth of inspiration, a block generally ameliorated in the climax by the writer looking hard at the life they have ignored—the burdensome family, patient fiancé, ruthless patrons—and finding the fuel for their art in the exemplary world the genius-in-question so impudently ignored. My enjoyment of this most superfluous and self-infatuated of genres is steeped neither in high-minded interest in the story behind my favorite texts nor in a pathological need to pollute myself with the spectacle of Johnny Depp inveighing mightily behind a silver prosthetic nose (as he does in The Libertine, false noses being second only to quills as the writerly biopic’s signature fetish). Rather, I love the ecstatic catastrophe that results when the two mediums flirtatiously interlock their ugliest parts and commit to film that vulgar and amorphous consummation: the act of writing.

Johnny Depp as John Wilmot in The Libertine.

Johnny Depp as John Wilmot in The Libertine.

There is a terrific variety in the depiction of writing on film, all of it wrong. I’m partial to the Rocky montage strategy, in which the writer finally gets down to business, words flying out of the typewriter, with superimposed transparencies of Shakespeare busts and breathy recitations of timeless sentences. But this is not to slight the tableau vivant approach, in which the real-life characters inhabit the roles of their fictional analogues, or the “all-nighter” fade, in which a mountain of pages magically appears on the desk by morning. There’s also something to be said for the materiality of typewriters in these movies, as they are pounded (because writing well means writing hard), lugged up and down stairs, thrown out of windows, and traded for booze. For this reason alone, I have nearly-only-nice things to say about The Man Who Invented Christmas—a virtual bingo card of writer-movie clichés, as well as one disguised as a Christmas movie—because it features the sweetest of stupidities: Charles Dickens writing A Christmas Carol in his upstairs office, seemingly alone but actually holed up with his characters, who whisper, titter, and shush one another as the great author struggles to do them justice.

The movie that exists around the writing scenes is pretty charming, in that it doesn’t actively wish bad things on its audience and plays all the hits (writer caught in a steep deadline, writer has long-suffering agent, writer reckons with his parents) with chummy congeniality. Downton Abbey’s Dan Stevens is great as an improbably curly-coiffed Charles Dickens scrambling to finish his holiday-themed novel (“A hammer blow to the heart in this smug satisfied age!”) with the help of an earthy Irish servant girl and stink-eyed Christopher Plummer, playing the phantasmal miser Scrooge that only Dickens can see. Highlights include Dickens’ rivalry with the foppish William Makepeace Thackeray, the sight of him marching into a store to demand “your finest cravats,” the discovery of the argot “humbug,” and the immortal caution that “We must not detain the poet when the divine frenzy is upon him.” All the varieties of writing-in-pantomime that I’ve described above (montage, tableau vivant, magic fade) ensure. Itch, consider yourself scratched. I also enjoyed Jonathan Pryce as Dickens’ spendthrift father who “bobs around like a cork on the surface of life.”

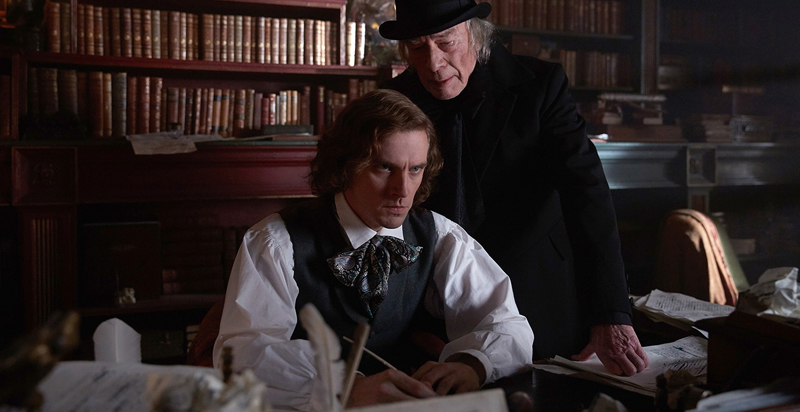

Dan Stevens and Christopher Plummer in The Man Who Invented Christmas.

Dan Stevens and Christopher Plummer in The Man Who Invented Christmas.

There is not much else to say about The Man Who Invented Christmas because it is precisely what it sounds like, and a hundred times more joyful than its contemporaries this season, the lachrymose Goodbye Christopher Robin and the grimly reverent Salinger biopic, Rebel in the Rye. Add to that the fact that while I do not care for Christmas movies, I sure love ghosts, and The Man Who Invented Christmas is obliged to feature at least three, meaning that to my mind the film breaks just about even.

Part of the problem with the biopic as form(ula) is that it bets that we would rather watch Shakespeare write Twelfth Night than go to a play, rather watch William Burroughs hallucinate than read Naked Lunch, and care either so little or so much about “Howl” that we need James Franco to appear onscreen as a kind of ambassador to the world of beat poetry. We seem to want to assure ourselves that, if we no longer appreciate anything called “art,” we love artists. Even outside of the scrim of biographical movies, writers make for serviceable protagonists, being precocious, elegantly wasted, and permanently embattled. I’m thinking of Barton Fink, Adaptation, Henry Fool, the execrable Finding Forrester, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and, why not, John Candy in Delirious or Will Ferrell in Stranger Than Fiction. Is this trend toward the private lives of writers more proof of the ascendency of autofiction, fiction that relates the life of the author while (supposedly) dispensing with artifice? The answer may depend on how willing you are to draw a straight line between Elena Ferrante and Johnny Deep (why is it always Johnny Depp?) mumbling “We can’t stop here! This is bat country!” in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, or between the Bard of Avon and Gwyneth Paltrow telling Joseph Fiennes “This is not life, Will. It is a stolen season.”

“We seem to want to assure ourselves that, if we no longer appreciate anything called ‘art,’ we love artists.”

If it is the case that we respond more to biographical writer-films than straight adaptations of their works—or, for that matter, their actual works—I sense I may be part of the problem. Because, look, I’d recommend The Man Who Invented Christmas to anyone looking to get along with their families for two hours and I’ve just about had it with A Christmas Carol itself. Besides the regional theater productions my Dad used to take me to every Christmas, I’ve seen it done with Muppets, Mickey Mouse, Flintstones, Smurfs, and Bill Murray. Besides, I like Ebenezer Scrooge and root for him from the beginning, only to watch my hero humiliated and laid low by sentimentalism, marketing, and crude supernaturalism. This is Dickens the crowd-pleaser—but the Charles Dickens of The Old Curiosity Shop and Bleak House would have known that the better story would end with Ebenezer unmoved, immune to the influence of his impecunious peers, and resolute in his convictions, prepared to live the last of his life as he did the preceding. A Christmas Carol is pure, premium cable-ready pap, which might be part of why The Man Who Invented Christmas is so inoffensive; it can’t do any worse injustice to reality than A Christmas Carol already has.

And yet (and I hope this isn’t the Ghost of Christmas Present speaking through me), The Man Who Invented Christmas does have something to say about the writing life. Late in the movie, when Dickens realizes that his maid Tara, with her old-timey spook stories, is the key to finishing his book, he finds that he’s had her dismissed; his father, whose past sins he can’t forgive, is an agony to him, but he learns to see him as an individual, not unlike one of his characters; battling with publishers and illustrators, he promises the moon, then panics about working hard enough to satisfy his contract. All these cases—the tendency toward neglecting people until they prove useful, feeling too close to the past to think objectively, or exaggerating your sales pitch until you have to actually manifest the work—seem like poignant approximations of someone’s real experience of writing.

Whether you hate them or love them, the literary biopic seems to be a regular feature of our present, especially in the holiday season. In the spirit of Tiny Tim, we may even call them blessings, every one—though surely God has nothing to do with it.

J.W. McCormack

Recent work by J.W. McCormack appears in VICE, Conjunctions, the Culture Trip, and the New York Times.