“Is That a First Edition of The Iliad?” Meet One of History’s Great Manuscript Forgers

On Constantine Simonides, a Mysterious Stranger in the Cotswolds...

In the summer of 1854, a purposeful and unusual-looking traveler arrived in Broadway in Worcestershire in west central England, with an overnight bag full of manuscripts. He was Constantine Simonides, a Greek who claimed to have lived among the monks of Mount Athos, and he certainly looked the part.

There are descriptions and several early photographs, showing him as swarthy and with glossy black hair thrust to one side and usually a great unkempt dense beard like an Orthodox priest. He was quite short but with a large head and exceptionally high forehead, of the kind which in popular myth denotes intelligence. He had prominent dark eyebrows and deep-set clever and piercing eyes—“a face not easily forgotten,” as was remarked. He was restless and voluble, as unceasing as the Ancient Mariner but usually in Greek. He looked as though he slept in his clothes, which were always black.

In a rural Cotswold market town of the 19th century, as unlike the dusty and sun-baked landscape of Mount Athos as is possible to imagine, Simonides must have attracted some attention. He was here to see Sir Thomas Phillipps, baronet, of Middle Hill, Broadway, who had invited him to stay the night.

Phillipps had a part in Chapter 7 of my book and stalked many times in and out of Chapter 8, like the wicked fairy, forever enthralling and provoking Sir Frederic Madden in London. Now it is time to visit him at home, which not so many of the manuscripts fraternity ever did. It is about three miles from the high street in Broadway out to Middle Hill. You turn south along Church Street, which quickly becomes Snowshill Road through the countryside, bringing you eventually to the medieval church of St Eadburgha, where Sir Thomas Phillipps himself is now buried. There is a place to leave the car.

Immediately opposite, on the left (or east) side of the road, are the stone pillars and old iron gates of what was formerly the main entrance into the long drive up to Middle Hill, with a Victorian gatekeeper’s lodge, whose current resident, pottering in his garden, kindly gave me directions and reminiscences of long ago. The way is now a public footpath called Coneygree Lane, rising steeply behind the lodge up through the woods eventually to the gothic folly of Broadway Tower at the very top of the hill. The track is rutted and muddy and it must have been a very steep ascent for visitors such as Simonides in a horse-drawn cab, or maybe he walked up on foot with his bag.

After about ten minutes the path branches out diagonally across a field with spectacular views of the green valley below, and from here, instead of climbing further, the old drive once turned right, as the man below had explained, now leading through a gate and past a couple of new cottages, to Middle Hill itself.

He was restless and voluble, as unceasing as the Ancient Mariner but usually in Greek.

It is a fine large and square 18th-century Cotswold stone house of two principal storeys with further attic windows above, added since the time of Phillipps. The old main entrance is in front of you from that direction, under a stone porch with three arches. I have been inside only once, many years ago. Visitors today reach the house up a modern drive further along Snowshill Road, more suitable for cars, and Middle Hill is now so thoroughly and comfortably modernized that it is hard to envisage today what Simonides would have experienced in 1854, stepping through the porch from the summer sunshine into a dimly lit house which was a packed and airless mausoleum of medieval manuscripts.

Thomas Phillipps was the illegitimate and only son of a very successful calico manufacturer in Manchester. His father had purchased Middle Hill in 1794, and Thomas was brought up here, without knowing his mother. An isolated and friendless childhood may have been what started Robert Cotton on the companionship of manuscripts, and Phillipps too as a solitary teenager was already spending beyond his allowance on the acquisition of books and manuscripts about local history and topography. His father died in 1818, leaving him a considerable income but an entailed estate, one which could not be sold.

The following year, Thomas married well, and his wife’s obliging family was able to secure a convenient baronetcy for him. The new Sir Thomas then embarked on a lifetime of self-importance and unmerited hauteur. Like King Lear, he had three daughters, whom he bullied and taunted with ever-changing hints of eventual inheritances.

All in all, Phillipps was not a very agreeable man, selfish, ill-tempered, grossly bigoted (notably towards Catholics), mean with money, litigious, and living forever in debt and on credit, as his dragon’s hoard of manuscripts at Middle Hill grew from a merely vast private library into the absurd, with thousands upon thousands of volumes crammed into every room, including corridors, staircases and bedrooms, often in tottering piles leaving almost no floorspace for access between them or filling wooden boxes stacked to the ceilings. The quantities of manuscripts simply astounded anyone who saw inside the house.

Of Phillipps’s passion and obsession, there is no doubt. Madden frequently described it as bordering on insanity. For this reason, I expect I would have enjoyed an evening with Phillipps (as Madden often did), as long as I was neither Catholic nor a tradesman and did not stay too long. His range of acquisition and interest was all-encompassing, extending with little discrimination from precious codices of late Antiquity right through to worthless manuscript papers of his own time. Many items were dirty and in poor condition, and Phillipps did not waste money on beautiful bindings or expensive repairs. The Abbé Rive would have been appalled.

Like the British Museum, Phillipps was actively seeking out manuscripts of every nationality, and he benefited greatly from the dispersals following the French Revolution and the political turmoil of continental Europe in the 19th century. All foreign languages were included, although Phillipps himself read only Latin and Greek, neither especially well. Whenever possible, he bought in bulk. (He could have been a candidate for the Oppenheim manuscripts in Hebrew, even knowing he could never read them.)

He kept a printing press on an upper floor of that neo-gothic tower at the top of Broadway Hill, part of the estate, where his harassed servants were made to print out numbered lists of the relentless purchases as they came in. A small oblong printed label with the number was then pasted to the spine of each book for identification.

By the time of his death, Phillipps had perhaps as many as 60,000 manuscripts, documents as well as codices. Madden was right that they would one day all be scattered. There is hardly a rare-book library in the world today without at least one or two manuscripts that were formerly crammed into Middle Hill or into the even larger Thirlestaine House in Cheltenham, where Phillipps later moved.

The collection took almost a hundred years to sift and disperse, beginning with a first auction in 1886, and I myself was initially employed by Sotheby’s in 1975 for the principal purpose of cataloguing the very last installments of manuscripts still being brought out in boxfuls from the Phillipps trove.

At the time of the visits by Constantine Simonides, Sir Thomas Phillipps was in his early sixties. His first wife died young and he had remarried. The childless and long-suffering second Lady Phillipps memorably claimed to have been “booked out of one wing and ratted out of the other.” Photographs of Phillipps at this period show an upright unsmiling man with greying hair, soon to be white, slightly overlapping the tops of his ears. He had a straight nose and thick mustache.

In pictures, at least, Phillipps appears carefully dressed in long dark jacket and white wing collar. Guests without business to transact testified to his courteous manners, but booksellers, competitors and most of his family despaired of his miserliness and single-minded obsession.

We are about to witness what was probably the third visit of Simonides to the baronet’s house. On the first occasion, in 1853, the previous summer, Simonides had brought to Broadway a bundle of manuscript scrolls comprising short texts by the early Greek poet Hesiod, supposed to be of very ancient date, including the celebrated Works and Days on the origins of agriculture and labour, composed around 700 BC.

There were ten narrow strips of seemingly old parchment, written on both sides in Greek, each about 10½ by 2 inches, attached together at the top onto a thin metal bar. Phillipps was sufficiently beguiled by the item to buy it. He had his printing press run off copies of a lithographed facsimile of its first lines of text, in a combination of large square Greek letters and a very strange-looking script resembling the spider-footprints of modern shorthand.

When the manuscript eventually emerged from the Phillipps collection for resale at Sotheby’s in 1972, it was obvious to 20th-century eyes that the writing was an utter fabrication of no antiquity whatsoever. Phillipps had struggled to read it, not surprisingly, and, in a bizarre inversion of reality, Simonides then offered his skills as a palaeographer to transcribe the Hesiod neatly for Phillipps for an additional fee of £150 (Phillipps countered with £25 for a partial transcription). Simonides assured him that the manuscript included at least one unknown work of Hesiod.

Phillipps had been to Rugby School and Oxford and this was exactly the bait to captivate a 19th-century Englishman drilled in the classics. All manuscript collectors are familiar with puzzled inquiries from unbookish neighbors as to what possible value there can be in gathering old books, and to have been able to announce the discovery of a lost classical text would have vindicated the entire library.

Later in 1853, Simonides had delivered five more scrolls of Greek texts to Middle Hill, comprising supposed works of Phocylides and Pythagoras and three Byzantine imperial documents. The receipt survives among Phillipps’s papers now in the Bodleian. Again, Phillipps agreed in principle to buy the items if Simonides could make transcriptions for him. In May the following year, Phillipps proudly showed these startling acquisitions to Madden in the British Museum. He, in turn, recorded in his journal:

I did not hesitate a moment to declare my opinion, that these were all by the same hand and gross forgeries; and I was grieved, but not surprised to hear Sir T. P. declare that in his opinion they were genuine (!) and probably relics of the Alexandrian library!!! Of course, although I did not express it to him, I feel the profoundest contempt for his opinion. In October last, when he wrote to me on the subject, I warned him against the purchase, but in vain. The vanity of possessing such rarities (supposing them to be genuine) has sufficed to counterbalance any doubts; and having paid a large price for these worthless specimens of modern knavery, of course Sir T. the more obstinately will defend their authenticity!

More was to come. Simonides had been hinting that he had a treasure greater than all these, nothing less than a classical manuscript of the Iliad of Homer. This was principally why Simonides was now returning to Middle Hill on 11 August 1854. By chance, we have a quite detailed record of the encounter because another visitor at that same time was the German map historian Johann Georg Kohl (1808–78), who was studying items in Phillipps’s collection for his own researches and described the event in his volumes of reminiscences, published in Hanover in 1868. “Among the other guests . . .”, Kohl recalled, “there was a Greek, whose name at that time was unfamiliar to me, but who had already made himself well enough known in the literary world. He . . . had brought with him various vellum rolls and pigskin volumes and like a pedlar had spread out his wares on the carpet, table and chairs.”

The most important of these was the promised Homer. Kohl recalled it as “a small, thin, closely written, tightly wound, long roll of vellum which the Greek declared was the most valuable thing he had at the moment to offer.” It comprised the whole of the first three books of the Iliad written in a script so microscopic that it all fitted onto both sides of a single scroll about 21½ inches long by about 2¼ wide, “so small,” wrote Phillipps later, “as not to be read without a magnifying glass.”

Everything about it was eccentric, including the layout, which opened with a kind of pictographic design of a Greek temple formed of lines of tiny script. The left-hand edge of the whole scroll was written vertically with one letter below another, creating a cascade of letters right down the scroll and then all the way back up to the top again and then down to the bottom once more, and so on, in what is known as boustrophedon, meaning resemblance to the path of an ox plough, back and forth, or, in this case, up and down.

It is a rare format known in archaic inscriptions on stone and pottery from the probable time of Homer himself, but then unprecedented in any surviving manuscript. It seemed a plausible indication of extreme antiquity. The text continued into the right-hand column in normal horizontal lines, as densely compacted as the grooves on a gramophone record. “Our conversation throughout the day turned on this remarkable object, and in the evening as well,” wrote Kohl.

These discussions must have been complicated. Simonides knew some English, more than he pretended (as subsequent events showed), and Kohl and Phillipps had some classical Greek, which they were mostly obliged to write down to be comprehensible by the other. Where had Simonides found the Homer? “The Man is so mysterious about his acquisition of these MSS.,” Phillipps wrote later in his printed catalogue; “a straight-forward honest person would state at once, with all candor, where he had obtained it, & how.” In another memorandum to himself, kept with the Hesiod, Phillipps recorded, “He told me that that he was Cousin to one of the Abbots of a Monastery on Mount Athos; that the MSS he brought were either found in a Monastery on Mount Athos or in Egypt.”

Several years later, Simonides modified this story to furnish further information. In 1859 a strange little book appeared by one Charles Stewart, A Biographical Memoir of Constantine Simonides, Dr. ph., of Stageira, with a Brief Defence of the Authenticity of His Manuscripts, published in London, printed in Brighton. The author is not clearly identifiable and the name was probably fictitious, but it may not be coincidence that it is a homonym of the Young Pretender and shares the initials of Constantine Simonides.

Phillipps, doubtless rightly, assumed that the book was really or mostly by Simonides himself, and certainly its careless orthography suggests material transmitted by dictation. In the Memoir, Simonides now seemed to remember that the abbot on Athos was his Uncle Benedict, that the manuscripts had been part of a library brought from Constantinople or Egypt by Saint Paul of Xeropotamou, son of the emperor Michael Kuropalatos (a real person, emperor 811–13), and that they had been hidden by the Orthodox monks beneath the ruins of a monastery on Mount Athos to save them from the Latinizers, or Roman Church, during the time of the Crusades.

The Memoir recounts that Simonides had acquired the manuscripts from his uncle when he was living on Athos and removed them on a private ship to Syme on 29 August 1840, three months after Benedict’s death. Detail was wanted: here it is, and the late Benedict could no longer confirm or refute it.

__________________________________

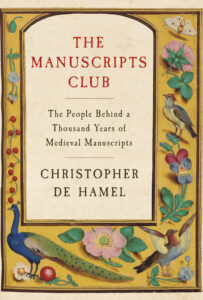

From The Manuscripts Club: The People Behind a Thousand Years of Medieval Manuscripts. by Christopher de Hamel. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Press. Copyright © 2023 by Christopher de Hamel

Christopher de Hamel

In the course of a long career at Sotheby’s Christopher de Hamel has probably handled and catalogued more illuminated manuscripts and over a wider range than any person alive. Since 2000, he has been Fellow and Librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The Parker Library, in his care, includes many of the earliest manuscripts in English language and history. He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Historical Society.