Is It Worth 1,000 Words? Mark Sarvas on Writing Art in Fiction

A Brief Survey of Paintings in Literature

Like so many readers, my first exposure to a painting in literature came from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In our first glimpse of the titular picture, it is described as no more than a “full-length portrait of a young man of extraordinary personal beauty.” We learn more about the picture through dialogue, as Lord Henry Wotton, who thinks it the best work his friend Basil Hallward has ever done, describes its subject:

I really can’t see any resemblance between you, with your rugged strong face and your coal-black hair, and this young Adonis, who looks as if he was made out of ivory and rose-leaves.

As a young reader, I didn’t immediately appreciate how quickly and how fully Wilde allowed me to perceive the canvas in question. If writing about music is like dancing about architecture, what is writing about painting? Unlike music, painting gives us something visual to hang on to but, for all that, it strikes me as only marginally less challenging to write about, moving something from its medium of strength—the visual, the seen—to a compromised secondary language that is forever striving to create, at best, an impression of an original that is always fated to fall short.

Yet literature is full of paintings, once you start looking for them. Most recently, a painting was the center of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, but the tradition goes far into the past. Proust is full of paintings, some named directly, others not. In the superb Paintings in Proust: A Visual Companion to In Search of Lost Time, author Eric Karpeles has mined the entire text for references to paintings and paired the appropriate image with Proust’s descriptions, like this one from Swann’s Way:

. . . as in those interiors by Pieter de Hooch which are deepened by the narrow frame of a half-opened door, in the far distance, of a different color, velvety with the radiance of some intervening light.

However, my favorite descriptions of art are found in the novels of John Banville, specifically his so-called “Frames” trilogy: The Book of Evidence, Ghosts and Athena. The Book of Evidence is centered on a murder committed during the theft of a painting, a portrait of a woman, vividly rendered here:

A youngish woman in a black dress with a broad white collar, standing with her hands folded in front of her, one gloved, the other hidden except for her fingers, which are flexed, ringless. She is wearing something on her head, a cap or clasp of some sort, which holds her hair drawn tightly back from her brow. . . In her right hand she holds a folded fan, or it might be a book. She is standing what I take to be the lighted doorway of a room. . . The darkness behind her gaze is dense yet mysteriously weightless. . . She does not want to be here, and yet cannot be elsewhere.

In an interview I did with Banville in 2005, he talked about his youthful flirtation with painting:

I just decided I would be a painter, at the age of 14 or 15. Bought some oil paints. . . I had absolutely no gift whatsoever. Couldn’t draw. No sense of color. These are distinct drawbacks if you want to be painter. And I plugged away at it for years, did these frightful daubs—I think my brother has some of them still. I have offered him good money for them so I could destroy them. But it did teach me about looking at things, looking at the world in a way that wasn’t just linguistic.

It is no surprise that Banville’s imagined paintings come so vividly to life. In a bravura turn in Athena, he creates eight 17th-century paintings on topics ranging from The Rape of Proserpina to Pygmalion. The paintings are attributed to imagined artists, each of which is an anagram or translation of John Banville, including Giovanni Belli and L.E. van Ohlbijn. At last, the novelist and painter are fully joined.

It always seemed inevitable that I would try my own hand at writing about painting. As a child of European immigrants who were obsessed with cultural betterment, a large part of my childhood vacations consisted of my parents dragging me off to this museum and that. I resisted it at first but grew to appreciate as I reached my teens. (My mother still tells the story of the time I was so deeply moved by Oskar Kokoschka’s The Bride of the Wind that I had to hurry outside of the Kunstmuseum Basel and catch my breath.) But my real engagement with painting came in my twenties, when I read Robert Hughes’s seminal work The Shock of the New, followed quickly by John Berger’s equally influential Ways of Seeing. For the next decade, I read everything I could about modern art, traveling to cities specifically to see museums and exhibitions (sometimes just to see a certain piece, as when I visited the Rothko Chapel in Houston). I amassed a decent collection of art books, and, like Banville, even made a brief and forgettable foray into oil painting.

When I began to write my second novel, Memento Park, which is a story of restitution, of a man seeking to recover a painting he believes was looted from his family in Hungary during World War II, I had my opportunity. Art plays an outsized role in the novel, which is full of painting references, some real and some created (though even the creations are based on actual paintings). My central painting, like Banville’s, is imagined but it is strongly based on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Berlin Street Scene. Throughout the novel, I borrow some of Kirchner’s paintings and re-purpose them for my artist, Ervin Laszlo Kalman.

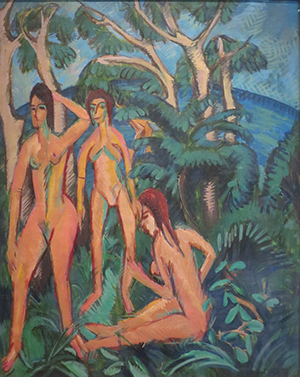

Bathers Beneath a Tree, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1913, Norton Simon Museum

Bathers Beneath a Tree, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1913, Norton Simon Museum

As part of my research, I made several visits to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, my favorite museum in Los Angeles. I knew they had a Kirchner there, even though it wasn’t a Berlin Street Scene. But I went out anyway, and the chapter of the novel set in the Norton Simon Museum is more or less as it happened to me that day.

Bathers were a time-honored subject from Cezanne to Picasso, and they were a recurrent theme for Kirchner. What moved me about this particular painting—beyond simply being in the presence of a physical object created by Kirchner’s hand—was the green serenity of the thing. I find Kirchner a jagged and unnerving artist (in ways I like), and this seemed like a refreshing breather from the dark hues of the Berlin Street Scene. In the novel, it’s described almost exactly as you see it here.

The Man with the Golden Helmet, Circle of Rembrandt, c. 1650, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The Man with the Golden Helmet, Circle of Rembrandt, c. 1650, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

When I was growing up in Queens, a copy of this painting hung at the foot of our basement stairs. It terrified me; his forbidding line of sight extended up the stairs, and I couldn’t pass the doorway at night for fear of his frightening visage. At the time, it was considered a Rembrandt, which is how I knew it, but in 1985 it was re-categorized; it’s not a fake (Rembrandt was a favorite of forgers) but likely the work of one of his students. Since Memento Park takes on, among other things, questions of authenticity and identity, this slippery history seemed especially relevant and hard to resist. The painting is no longer at the foot stairs, though in my mind’s eye, it lives there forever.

Self-portrait, 1860, Bertalan Székely, Hungarian National Gallery

Self-portrait, 1860, Bertalan Székely, Hungarian National Gallery

Leda with the Swan, after 1871, Bertalan Székely, Hungarian National Gallery

Leda with the Swan, after 1871, Bertalan Székely, Hungarian National Gallery

Though it’s a work of fiction, Memento Park draws heavily on my relationship with my father. He wasn’t the most demonstrative or talkative of men, but later in his life he opened up more about his youth in Hungary and his time in the war. When he was in hospital, during the last weeks of his life in 2009, I asked him about where he’d grown up, and he mentioned the name of his street, which was named after a famous Hungarian painter, Bertalan Székely. (“Convergences infect this tale,” my narrator warns.) He didn’t know at the time that I was writing an art-themed novel that included him; it was another of those accidents (or convergences) that suggests that you’re on the right track.

A few years later, I went back to Budapest and visited his apartment on that street. I also spent an afternoon at the Hungarian National Gallery to look at their collection of Székely’s paintings. (Both scenes occur, in fictionalized form, in the novel.) Given my devotion to modernism, I was largely unmoved by his work, which seemed conventional and mannered. In the novel, I compare his handling of nudity and eroticism (as in Leda, and others) unfavorably with Matisse’s earlier nude. But I was struck by his self-portrait, which was almost shockingly handsome. Of course, these are usually idealized selves (though compare it with Kirchner’s shattered self-view), and since I couldn’t find any photos, I’m unsure how true to life the image really is. But I was moved by the romantic, confident tone of the portrait, and it made me like him just a little more.

Mark Sarvas

Mark Sarvas is the author of the novel Harry, Revised, which was published in more than a dozen countries around the world. His most recent book is Memento Park. His book reviews and criticism have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Threepenny Review, Bookforum, and many others. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle, PEN/America, and PEN Center USA, and teaches novel writing at the UCLA Extension Writers Program. A reformed blogger, he lives in Santa Monica, California.