Intrigue, Not Critique: On the “Portrait of the Artist” Feedback Model

Florence Gonsalves and Matthew Vollmer Discuss Democratizing the Writing Workshop

“Why does bringing a piece of writing to a creative writing workshop often feel like delivering it to the hospital, or worse, the morgue?” Professor Matthew Vollmer asked, during one of the first classes I took with him in the second year of my MFA program at Virginia Tech. “I’m not saying that the traditional approach, where you bring in a single piece and ask a bunch of people to read it and give you feedback while you sit there silently, lips zipped, taking notes, isn’t without merit.

Literally any and everything one writes can likely be “improved,” especially with the help of other readers. But at the same time, the constant diagnosing of a work’s illnesses can prove exhausting. It can make workshop feel like something to endure. And at its worst? It can seem like a punishment.”

Um, yeah, I thought. But what to actually do about it?

This issue isn’t new. Many scholars have challenged the “traditional” model—the one popularized by the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and championed by countless other universities, MFA programs, and organizations—including Liz Lerman, Matthew Salesses, and Felicia Rose Chavez. While Lerman’s Critical Response Process suggests strategies that implement student agency such as statements of meaning and permissioned feedback, and Chavez and Salesses’s anti-racist pedagogies emphasize a myriad of steps to promote student voices, including post-workshop one-on-one conferences, such workshops still tend to adhere to the prevailing and dominant model: a student brings a single piece of writing to workshop and receives feedback from peers.

In order to honor students of diverse backgrounds, especially BIPOC and LGBTQ+ writers who have been traditionally silenced by antiquated, racist pedagogies that push traditional “gag-rule”-style workshops, creative writing educators have a responsibility to uproot the foundations of the creative writing workshop, reimagining the space as an enlightened, democratic counterculture.

What follows is a conversation between Professor Vollmer and myself concerning the origins, components, and impacts of an alternative method of sharing work in creative writing courses called “Portrait of the Artist Workshop” (or “POTA”),the basic structure of which is as follows: The writer who is “up for workshop” shares a Google folder with four sub-categories: “My writing,” “Influences,” “Photos” and “Obsessions.” The student then fills each sub-folder following these loose guidelines, and culminating in a “POTA guide” which reflects on the assemblage of their folder, what the writer wants help with and doesn’t, status/progress on pieces, and how they want to conduct class for their POTA workshop.

*

Florence Gonsalves: Can you explain the components of the POTA assignment/workshop?

Matthew Vollmer: Sure. It’s basically a scenario that involves the participation—and good will—of everyone in the room. In this version of workshop, the writer not only speaks, but is invited to interrupt—and even guide—the workshop process. And rather than submitting a single piece, the author submits a digital folder that includes copies of their own work, examples of influences and obsessions, and other relevant ephemera, with the understanding that writing is 1. a social act, 2. an art, and 3. an enmeshed web of interconnected energies that, if examined with curiosity and wonder, will reveal trends and patterns the author is already in pursuit of, whether consciously or not. The focus of this workshop, then, is intrigue rather than critique, and its focus is on raw material and process rather than finished product.

The focus of this workshop, then, is intrigue rather than critique.

Each Portrait of the Artist workshop begins a week before the class meets. Let’s say that this particular class period—ideally 75-minutes in length—is dedicated to workshopping the work and vision of a student named Mary. Mary has chosen to share four folders with the class—“My Work,” “Obsessions,” “Influences,” and “People, Places, Things”—that contain digital representations of her own personal vision and artistic influences and which include (but are not limited to): a song by Lana del Ray, a clip of Nightmare on Elm Street, photos of her boyfriend and her mom; a Twin Peaks meme of the Black Lodge and the caption “I WANT TO HOT BOX THIS ROOM”; the poem “Toast” by Leonard Michaels; a still from The Shining of a distraught Shelley Duvall gripping a baseball bat; a still from Rebel without a Cause featuring James Dean; a photograph of red and green traffic lights in a snowy intersection; “Nighthawks” by Edward Hopper; Lydia Davis’ paragraph-long story “Happiest Moment”; a still from It’s a Wonderful Life bearing the subtitles “What do you want? You–You want the moon?”

Mary decides to spend the entirety of workshop the “normal” way, which is to say, by asking the rest of the class to identify patterns and preoccupations they observed in her POTA folder; to provide brief thoughts and general feedback on the short stories Mary uploaded; to generate potential and individuated writing prompts, and to identify other artists that her work might be in conversation with.

Members of the class note that Mary seems drawn to Americana, moons, liminal dreamlike spaces, and snowy Midwestern tableaus that feature cozy houses. As the dialogue unfolds, themes emerge. White space. Quietness. Romance. Violence. Abundance. Decadence. Voyeurism. One student notes that, in Mary’s work, characters tend to “do romance wrong, but it’s right,” and that both the writer and her influences seem to be taking comfort in representations of the bizarre.

“The images, both in her flash fiction and poetry, seem to be in conversation with the lonely, evocative photographs in her influences folder,” one participant notes.

“It’s like, as a reader or watcher, you’re invited to dust for fingerprints,” another observes.

“Or like someone’s pulling the curtain back,” another adds, “and you’re allowed to witness something surprising and intimate.”

Let’s say that Mary thinks all these observations are wonderful to hear, but her main problem—as she sees it—is that she feels like she keeps writing flash fiction but what she really wants to do is write a novel.

No problem. Her peers—and her professor—stimulated by this multimedia cascade of “Things Mary Loves,” have ideas.

What if Mary made a list of everything she loved and held dear—a la Ursula K. LeGuin’s “Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction?”—and wrote a novel with all of those glorious treasures inside? What if she envisioned her unwritten novel as a kind of Advent Calendar—thus honoring her obsession with windows, with wintertime, and outsiders looking in–and behind each window lived a tiny story, the compilation of which contributed to a larger narrative?

What if, instead of avoiding writing about her home state of California, she forced herself to really “go there”? Oh! And had she ever read Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel Elieen? Was she familiar with the work of Gregory Crewdson, who employed film crews to compose surrealistic portraits: a woman floating right-side up in a living room, say, or a lone man in a suburban neighborhood gazing into a beam of light falling from an unknown place in the sky?

At the end of class, Mary regards the whiteboard full of notes the professor has taken during the workshop. She’s beaming. She expresses gratitude towards her peers for their time, care, and attention. She’s pleased because she feels like she’s been seen and heard, having held workshop on her own terms. Her voice mattered, as did her vision. Instead of a swarm of contradictory voices in her head surrounding a single piece presumed to require critique to save it, she can now lay claim to an abundance of observations and reflections on her body of work, future directions. She leaves with possibilities.

This is what a Portrait of the Artist workshop looks like.

FG: So how did all this come about? Can you give a little background on the history of POTA?

MV: About five to six years ago, I taught a generative workshop—one that asked students to write something new each week and to take turns workshopping what they produced. I hadn’t realized until I read my evaluations at the end of the term that a number of the students had found our workshops to be tedious, but apparently that was one of the takeaways. I ended up confiding in one of my students, an Australian writer named Beejay Silcox; her sense was that workshop could be enlivened somehow.

As it was, the model for workshop was this: class after class, students brought in work as if they were delivering sick patients to a hospital—or worse: corpses to a morgue to be autopsied. The assumption, in every workshop, was that something was “wrong” with a piece, and as promising or effective as the writing within that piece might have been, it seemed like students were preprogrammed to put on their detective hats and begin searching for clues as to how and why the piece being workshopped could be better.

Beejay and I decided that we wanted a new, more robust and dynamic alternative to the “sick/dead patient” model. We wanted vibrancy and life. We wanted dialogue. We wanted to create something where the writer—the artist—could be seen and heard. We wanted whatever process we came up with to center on discovery. And so the Portrait of the Artist Workshop was born.

We wanted whatever process we came up with to center on discovery.

FG: As a professor, what impacts have you witnessed that POTA has had on students?

MV: POTA workshops are legitimately always surprising. The structure presents an occasion for a writer to reveal idiosyncratic obsessions, influences, desires, fears, and avoidances. And every one is different, from the materials that the writer gathers to the ways in which the writer structures their workshops, to their takeaways and further steps.

FG: I definitely saw that when I completed my POTA workshop. As a student struggling between two genres (poetry and fiction) and writerly identities (“Y.A.” voice versus “literary” voice), POTA helped me resolve and reconcile those apparent differences to see the overlap across the content I create and consume. I was positioned as the expert of my POTA and my workshop (a whole 75 minutes to do whatever I wanted!) but I was encouraged to inquire about myself as a writer and so I also brought “beginner’s mind” to my workshop.

Including several pieces of my own that I liked, alongside ones I had questions about, gave me an opportunity to reflect on my writing process, skills and weaknesses. Seeing these in light of my other formative influences and experiences as an artist conveyed a much broader, less limited concept than just a writer evaluated by a single piece, genre, or concept.

MV: Yes. One major takeaway of POTAs is how it elevates the classroom community. Everyone tends to feel like they’re all on “the same team.” Because we are. We’re all writers helping others and ourselves find themes, patterns, obsessions, and blind spots. Our stories and essays are not treated like dead bodies whose manner of passing a coroner is trying to ascertain. Instead, each work gets presented in conversation with a constellation of related and unrelated media. Entering into a conversation about these texts and various media incites wonder and curiosity; when someone is enthusiastic about a painting or a song or a story—much less a whole volume of like materials—enthusiasm tends to be contagious.

Even if the other people in the room don’t particularly “like” the kind of music/poetry/memes being presented, they recognize patterns and obsessions and preoccupations and appreciate them because they’re rooted in a human being who is taking them seriously. This focus on influences and appreciations steers everyone away from the main mode of a traditional workshop, i.e., critique. And while there is indeed room for critique in a POTA workshop, it tends to happen on the artist’s terms…and furthermore is only one part of the response. If the disposition of a “normal” workshop is critical, the disposition of POTA is much more multifaceted, and foregrounds wonder, hope, curiosity, inquiry, care, and love.

__________________________________

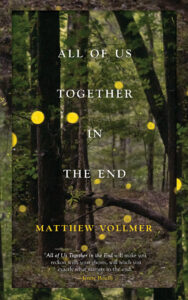

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer is available from Hub City Press.

Florence Gonsalves and Matthew Vollmer

Florence Gonsalves is the author of Dear Universe and Love and Other Carnivorous Plants.

Matthew Vollmer is the author of six books, the most recent of which, All of Us Together in the End, will be published by Hub City Press this spring.