Interview with an Indie Press: Melville House

Dennis Johnson and Valerie Merians on Risk, Change, and Making Mistakes

If you’ve spoken to me at all in the last two years, I’ve probably found a reason to bring up How to Do Nothing, a book that seamlessly brings together philosophy, history, technology, and (importantly!) bird-watching, all to identify and address our society’s crisis of attention.

The book, which grew from a lecture that author Jenny Odell gave in 2017, draws equally from those disciplines and Odell’s own experience as a visual artist, is difficult to classify. Odell’s argument—that the attention economy’s intrusion on our mental space does harm, and that resisting it involves connecting to the landscape and a less marketable approach to information—was an odd fit for the world of book publicity in 2021. As Odell herself described at the XOXO Festival in 2019, “Trying to make an even gently anti-capitalist book to sell it, or to write about the attention economy in the attention economy, can feel like trying to play ball on a planet with weird gravity.” Acknowledging that Melville House “did an amazing job” working with the book, she said, “It’s been anxiety inducing to watch the discourse of marketable usefulness try to appropriate a book about militant uselessness.”

This kind of paradox is one that many publishers might have preferred to avoid entirely, regarding the book as a risk. For co-founders Dennis Johnson and Valerie Merians, though, this kind of risk is inescapable, and not always unwelcome, in indie publishing. Having founded the press in their Hoboken home in 2001, they’ve been publishing nonfiction on a wide range of topics and fiction—including from Nobel Prize-winners Imre Kertesz and Heinrich Boll—ever since.

They joined me on Zoom from their current office in Brooklyn to talk about the crash course they received in printing, the choices they wouldn’t make twice, and adjusting to change in the publishing landscape.

*

How would you describe the benefits to working at an independent press?

Valerie Merians: Because it is our press and we started it, I guess it would be that we can publish what we want, within reason. We have to stay in business and that’s always the first priority, but within the constraints of keeping the lights on, we can take a lot of latitude that I know other publishing houses would want to take themselves. We can move quickly and we can be really responsive, which can be very exciting when there’s current-events books that we’re working on.

“We did what you would tell your children to never do.”

Dennis Johnson: For us as owners and for the employees, I think the appeal is that it’s a mission-driven company. You’re never going to make money in this business. You’re not going to make what you might make at a big house, but the reward is that you’re working on meaningful books every time out. We’re not driven by the bottom line the way corporate publishing is.

*

What about the challenges?

DJ: Lack of money.

VM: Publishing is a very small margin business. It’s never been a lucrative business. … You’ve probably heard this joke: How do you make a small fortune in publishing? And the answer is, you start with a large fortune. It’s never been a particularly lucrative business. And people usually get into it out of love for the books, but the constraints are financial primarily, and secondarily, I would say just the time. It’s a very labor-intensive process.

DJ: Especially when you publish the kinds of things that we specialize in: you know, justice books, debut writers, other extremely work-intensive, low-profit books.

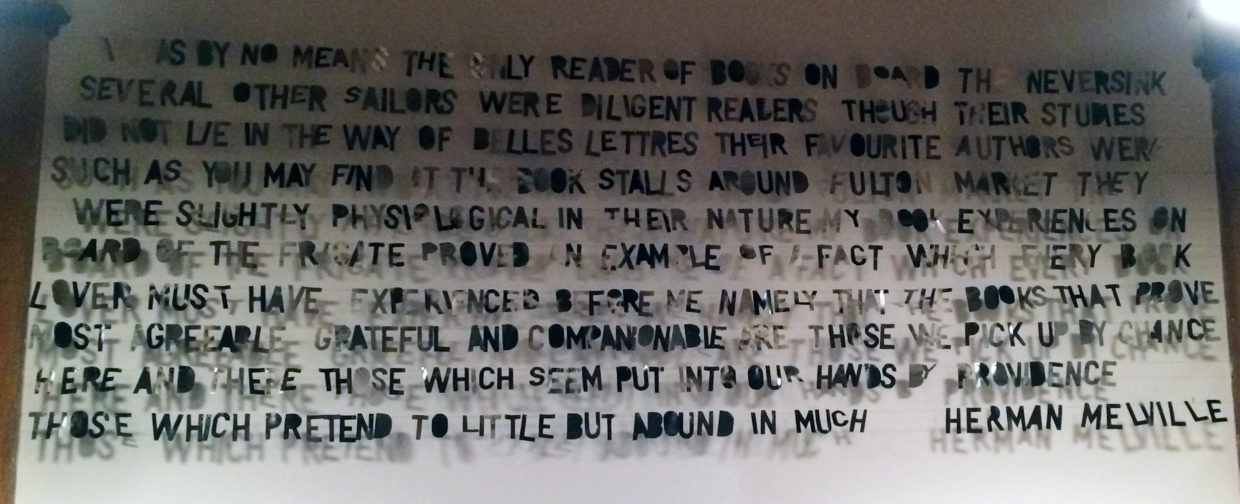

A quote from Herman Melville’s White Jacket hangs in the offices of Melville House in Brooklyn. Artwork by Jeri Coppola.

A quote from Herman Melville’s White Jacket hangs in the offices of Melville House in Brooklyn. Artwork by Jeri Coppola.

*

Have any titles in particular been game-changers for your business?

DJ: Publishers work with the same kind of delusions that authors work with, which is that every time out you think it’s going be The Beatles. It’s going to be, you know, the revolutionary avant-garde piece of work that, amazingly enough, the mainstream media will adore and it will make everybody’s dream. In reality, of course, that very rarely happens so that when it does, you’re pleasantly surprised. [How to Do Nothing by] Jenny Odell is one example. We thought that was a very good book and that it would do very well, but it really exploded.

Debt by David Graeber was a much longer slog. Nobody believed in that book except us. It was an extremely hard sell, even internally. It took months and months and months to make that book a hit but when it did it just rolled and rolled and rolled along. Every Man Dies Alone by Hans Fallada was similar, although I always thought that was going to do well, but when it did, I was still surprised.

VM: We knew it was a great book. That much we knew. It’s really just, can we get enough people to the book? Can we really get the word out? That’s always the challenge.

*

What are some of the risks you’ve faced as a business?

DJ: Just starting the company. We did what you would tell your children to never do.

*

So, the risk was having a business in the first place.

DJ: Not just having a business, but funding it the way we did: with our own money, with credit cards, we emptied out our bank accounts. I had a very small retirement fund from my life as a college professor and I emptied that into the company and just really put everything we had into it. You’re never supposed to play with your own money; that was an amazing risk, and if our first two books hadn’t been successful we wouldn’t be talking to you. It just worked out really well.

A lot of the first things we did, we did because we didn’t know better. We might not do the same things today. But we did them and it kind of made the company stand out. We were immediately seen as this cool, interesting company when in fact, we were fingernails on the edge of the cliff.

“Every time we think, okay, we get publishing, we get how it works, it’ll completely change.”

Our first book, we didn’t really know how to communicate with printers, for example. We didn’t know—it’s just us. We didn’t know how to tell them about the cover when they printed it. Our first book was a book called Poetry After 9/11 and it had a beautiful photograph from a friend of ours of the World Trade Center taken from the Staten Island Ferry, in sepia tone, just a beautiful picture of the rippling water leading up to the towers. When they printed the book, it came out Pepto-Bismol pink. It was our fault. We just didn’t know the language of that sort of thing. And so we had them rip the covers off and do them again. … You literally actually rip the cover off and then paste on the new cover, and it was extremely expensive. But we were coming into the business as artists and we just said, “This has to be right. We don’t care about the cost.” Today, we would probably publish a pink book.

*

It sounds like a crash course.

VM: Honestly, we’re still on that curve. Every time we think, okay, we get publishing, we get how it works, it’ll completely change. Every two years, it feels like publishing just changes—like something enormous happens, like e-books happen and Borders goes down and Amazon takes over the retail space. It’s just been an incredible 20 years of really radical change for a very stable kind of industry.

DJ: A lot of the change we were ready for, maybe more so than other publishers. Melville House came out of my blog, MobyLives, so we were already kind of into digital media and using the Internet for alternative media and marketing. We were pretty ready for a lot of things that happened … It’s like bookstores, a lot of them had great websites. A lot of them didn’t. So when the pandemic hit, some of them were more ready than others.

*

How has the coronavirus epidemic changed your work?

DJ: It’s extremely hard, it’s extremely frustrating. … It’s a terrible kind of lock up. That’s been the hardest part—keeping people’s spirits up, keeping people focused.

We’re a really collaborative company. Right now we’re in the office—nobody else is, everybody’s working from home, but we’re sitting in our conference room, which is just this long table where we sit around with staff and we brainstorm projects, and we like to really attack things as a group, so we can be at a meeting and you don’t have to be a publicist to shout out a good publicity idea, you don’t have to be an editor to shout out a good book idea. That[‘s what] we really miss, the kind of collaboration that just happens from being in the same room.

*

Are there any projects that you’re particularly excited about at the moment?

VM: I’m excited about a book called Privacy is Power. It’s about reclaiming privacy and the importance of doing that as a culture. … It’s a more public facing kind of rallying cry, the importance of maintaining our privacy and what that means for us as a culture. It could posit a very, very dark future, should we lose hold of the idea that our privacy is primary. It takes very complicated ideas and it’s very simply put forward; she has simple things that we can do right now and steps that we need to be taking. That’s coming in April.

DJ: I would like to shout out a novel. One of one of my favorite writers, kind of a personal discovery, is a guy named C.D. Rose. We’re about to publish our third book with him. The first book we did with him was called The Biographical Dictionary of Literary Failure. … He’s a British writer and he’s kind of a mysterious guy, even to me. He’s a discovery I’m very proud of. We haven’t got him on the bestseller list yet, but I’m not going to quit until we do.

*

How do debut authors reach you?

DJ: Well, let’s just say there are no shortage of books in front of us; even though we don’t accept unsolicited submissions, somehow they make their way. Authors are recommended to you by your other authors or by friends or other publishers or whoever. And we’re looking.

We do a certain number of agented books. I have a reputation for being anti-agent—it’s inaccurate. We do a lot of agented books. I just prefer working directly with the authors and discovering authors and they’re often unagented, but we have other editors and probably 60, 70 percent of our books are agented.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.