Instead of Writing, Margaret Renkl Forages for Fungi

“Always I find more answers in a forest than I find in my own hot attic of a mind.”

I’d finished writing, I thought, when I sent the essay to my editor, but my editor had other ideas. Questions came back for which I had no answers. Suggestions came back with which I did not agree. The clock was ticking, I knew, and in New York the clock ticks faster than it ticks here in Tennessee. I went to the woods anyway.

People often ask how long it takes me to write an essay, and I wish I knew how to answer. When I start, I don’t know where I’m going, and I don’t know what wandering route I must take to get there. The whole thing is an exercise in faith. It begins with an image, a feeling, a vague sense of why something matters to me. It never begins with a plan. I just start writing and trust the words to keep coming. I need the words themselves to guide me, to tell me where to go and why. When I lead workshops, I tell young writers to write. That is my whole pedagogy: Just write. Trust the words to come. If they don’t come, go for a walk.

Always I find more answers in a forest than I find in my own hot attic of a mind. Scientists have made studies of the walking brain, and the results are dumbfounding. Given a test that measures creativity, college students sitting at a table produced unremarkable results. But when scientists put them on a treadmill, or sent them for a walk around campus, their brains lit up like the night sky. The students who walked produced 60 percent more original ideas than the students who were seated.

The study measured only the cognitive effects of a body in motion, walking on a treadmill or along a familiar route. I would like to see an fMRI image of a mind in a forest, even one as carefully managed as my local park, where the trails are mulched with donated Christmas trees. A forest so small that the cars on nearby roads are audible from every place on the trail.

It was raining the day I was on deadline, and I like the woods best in rain. There are fewer people on the path. The dampness softens the ground and muffles the sound of my own footsteps. The heat-dulled leaves of the canopy grow visibly greener. The understory goes greener still.

Best of all, in a wet world deadfall and soil erupt into fungi. Delicate whorls of polypores make a bouquet of fallen pines. Bright elf cups are scattered across the leaf litter as though a parade has passed by. Glowing angel wing mushrooms fruit on the hemlock like a bridal veil trailing along the path. Chicken of the woods make yellow and orange ruffles fit for a square dancer’s skirt. Oh, their marvelous fungi names! Firerug inkcap, turkey tail, witch’s hat, stinkhorn, jelly fungus, shaggy scarlet cup!

These are flowers of the shady forest, the silent scavengers of deadwood and rotting leaves. In living trees, they can form a symbiosis, colonizing roots and helping trees absorb nutrients, creating vast underground networks that allow trees to communicate with one another and even share resources. In dead trees, fungi soften wood, making it hospitable for insects, a place that can be carved out by birds in need of a nesting site, or animals in need of a hiding place or shelter from the cold. Fungi, too, can turn death into life.

Oh, their marvelous fungi names! Firerug inkcap, turkey tail, witch’s hat, stinkhorn, jelly fungus, shaggy scarlet cup!

I rely on apps and field guides to identify mushrooms, but their color variations seem to be endless, and I have no idea if I’m right. I would never eat a mushroom that grows wild in the woods. There are too many ways to be dead wrong, an adjective I choose deliberately, and too many purposes for fungi when they remain in the woods. I squat, I admire, I take pictures, I move on.

In one fallen tree, the transformation has been unfolding for so long that a little cave has opened up where a branch once joined the living oak. Over years, dead leaves collected in the cavity and turned into soil. In the shelter of that death-opened place, new green life has sprung up: moss and clover and some sort of trailing vine I can’t identify. In the center, as carefully arranged as if a florist had planned it for a centerpiece, rises one woodland violet. Every time I see it, I remind myself to come back in springtime to see it in bloom.

By the time I reached the violet that day, I had already stayed out too long, but suddenly I understood how to fix the problem in my essay. I texted my editor to tell him I was on my way back to my desk. As an apology for my tardiness, I included a photo of the secret terrarium in the fallen oak.

“Like a little tree womb,” he wrote back.

And that’s exactly what it is. It’s what all trees are when we leave them alone.

__________________________________

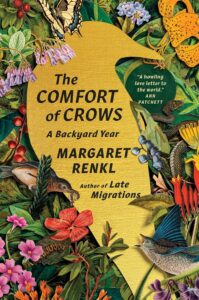

Excerpted from The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year by Margaret Renkl. Used with permission of the publisher, Spiegel & Grau. Copyright © by Margaret Renkl.

Margaret Renkl

Margaret Renkl is the author of Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss and Graceland, At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache From the American South. She is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times, where her essays appear weekly. The founding editor of Chapter 16, a daily literary publication of Humanities Tennessee, and a graduate of Auburn University and the University of South Carolina, she lives in Nashville.