6:15 p.m.

He was sitting at the Terrace Café somewhere in Haya Hulet and watching the people going up and down the road. The day had been long, and the setting sun seemed to promise an even longer evening. His body was tired, but his mind continued to churn with a nagging persistence. It had been more than fifty hours since he last slept. He feared if he went home he would not be able to fall asleep and would have to walk through the streets again. Based on how he was feeling now, he was unsure if he would ever sleep again.

The street was bustling with cars and people on their phones. Across the street, there was a private hospital with visitors pouring in and out and tires squealing when they pulled into the parking lot. As he ordered, he remembered that coffee had caffeine, then realized the caffeine would have no purpose since his body had stopped responding to stimulants.

The girl who served him gazed intently at his face as she gently set down the cup. She was expecting him to recognize her, but he was too tired to recognize anyone, and focused his attention on the oily-looking liquid in front of him. When the girl started to walk away, however, he began to notice her, especially how her pants fit her so well that day. Her body almost seemed malleable, taking the shape of the clothes she wore. He stirred the coffee, thinking about how the fabric looked so rigid that it must be abrasive.

When he turned his head toward the street, he sensed that the rhythm of pedestrians and cars had quickened, and his heart began to pick up its pace as if to match the commotion outside. He pressed his hands to his temples and felt them throbbing. I must get some sleep today, he promised himself. The noise was making him more and more tense. Amid the traffic, taxis stopped and lured people with their honks, and people were running around with seemingly no sense of direction. The laughter, the whispers, the woman pulling along her children with runny noses, parking attendants writing on tickets, tacking them under wipers—all of this brought up an urge in him that he had to fight against. He could visualize this so clearly, the bottle of Baro’s dry gin just at his fingertips. While he was fighting the urge, the madness of the street seemed to settle down. He eased into a daydream, thinking of the woman with her lipstick-smudged matchbox and her laughter. He caught himself getting lost in the wheels of memory, and returned his attention to the street.

He saw a group of girls all in the same clothes and walking in perfect sync. He studied them closely, wanting to register them in his catalog of beauty. Then he counted more than a dozen men who had shaved heads—the local skinheads with their shiny scalps. Looking at them from where he sat, he imagined how cold they must be and began to worry because he believed their heads were made of something soft like the shell of a boiled egg.

6:27 p.m.

He finished his coffee. He heard a voice in his head say, Go home and sleep. Stop thinking, go to sleep. He wondered if somebody could hypnotize him. A part of Yannis’s piano routine rang in head.

He heard the laughter of a girl. That spontaneous laugh that would start casually then extend like she was imagining another layer to the joke, or she was combining all of the laughter she’d had throughout her life in that one moment. Once she began to laugh, it would go on and on until everyone laughed alongside her, contracting her glee. She would get worried in the middle of her laughter that it was going to die suddenly, and would refresh it by extending it with sounds that had nothing to do with laughter.

6:28 p.m.

He shook his head and turned his attention back to the street.

A man got out of a taxi and walked toward the private hospital. He was holding a construction helmet, which he placed over his head once he reached the entrance.

He thought that he had made it up—it made no sense that a man would wear a helmet to enter a hospital to visit a patient. If what I did see was real, he thought, then those skinheads should learn from him and protect their soft heads.

He waited for the man to come out. When he didn’t, he called for the waitress and paid. This time he smiled and she smiled back. She had teeth like the tines of a fork. When she turned, clanking his cup on the tray, he studied her from behind, and continued to do so even after she was gone.

6:49 p.m.

As he stood up, the urge came to him again. This time he knew he couldn’t fight it. His body was tired, he had a headache, and he was having memories that made it feel like something outside of him was ordering him about. His body begged for sleep and though he would have gladly granted it, he had forgotten how. If he went to a bar and spent another night without sleep, he knew he was going to damage his brain. He began to sweat. He didn’t want to go home anymore. He knew that if he went and couldn’t sleep, he would probably go mad and take rat poison, or do something else very unpleasant.

He wanted to call somebody but he had nobody that he could call. Everyone he wanted to call was either dead or from his imagination.He vaguely remembered the other boy they told him about: how the boy took an extra dose of rat poison before running away from home, how they searched for and found him two days later and he wasn’t dead. They took him to a hospital and admitted him into the psychiatric ward, and he began covering his face with his shirt after that to hide from people . . .

Another time, everybody laughed in a taxi when a friend was telling him how, in his old neighborhood, they had brought back a man who had stepped on a land mine on the battlefield. Everybody laughed when he explained how they had taken him home in a bucket because he’d been blown to pieces. They brought him home because he loved his mother and refused to die without seeing her. He was dead serious when he told the story and was trying to make a point that the debt of death must only be paid when one is ready and not when it is due.

7:30 p.m.

He wanted to call somebody but he had nobody that he could call. Everyone he wanted to call was either dead or from his imagination. Now the memories were becoming vivid, like he was watching a movie made especially for him without a beginning or an end, a movie intended to drive him wild with regret. It played inside the deep recesses of his soul, with scenes powerful enough to remove him from reality. It was a movie he couldn’t choose to walk out of, and the movie’s score was Rachel’s terrific laughter.

He decided they were in love. Rachel knew all the sounds that ought to exist, and it was those sounds, that voice, that would not let him be. They kept lingering even after she was gone, and prevented him from sleeping.

Henock could never sleep. He had gotten a desk job at some office as a clerk. Mornings were horrible for him, but he got there on time and slept while working in snatches. After lunch he chewed khat and would be like Lazarus, resurrected back from the dead.

Even as a kid he’d never slept as soundly as he should have. He almost never slept without a nightmare. There was always something picking up his bed or dropping him into a bottomless pit, or hairy spiders chasing him or cold hands holding his feet, sliding him down through the grills of the bed.

He wanted to be his old self again and be with the girl, wanting to hear her laugh. He also wanted to rinse his mouth with a gulp of gin that stung on the tongue and ate away his brains when it was supposed to make his memories go away. He wanted to forget. He knew that once he could forget, he could get some sleep.

8:50 p.m.

In the bar while he waited for sleep to come, he had to drink quickly to slow down the movement of the people around him. His nose cleared suddenly, sharply, making the air he breathed in feel like acid, bringing tears to his eye. There is no single reality, something inside him thought, as there is no single truth, or meaning to life or love or God.

“Why can’t I yawn?” he said aloud to himself. He feared he had forgotten how to do that as well. He remembered his grandmother’s meek voice, her humming the gospel ringing in his ear. To drown the voice out he clanked the ashtray with a glass, but it didn’t work. The waiter came and he ordered another drink.

He wanted to be his old self again, playing the role of a younger and better Henock.His stepfather’s mother was of a different sort. She was always in constant motion: visiting people, helping around funeral homes, comforting mourners. She was a sociable old woman, but that wouldn’t thoroughly describe her. She was known for doing things that seemed to completely contradict each other but would be normal in her eyes. She once helped some people move their fences over to their rich neighbor’s lawn so that they could have more space. When the neighbor returned and wanted to know who was behind the debacle, she helped him by telling the truth and even went to court to testify against herself and the others. After they were fined and her neighbors deemed her as untrustworthy and two-faced, she still went on being their friend and would go out for coffee with them. Or, in another case, she would always say that she hated Henock’s blind grandfather. Yet she would spend hours after hours in his company and would prepare his meals. Once, she gave him his food on a plastic pan that children would sit on before learning how to use the toilet. When Henock asked her why she would do such a thing, she said that it was because the pan had never been used, and besides, a blind man could never tell the difference.

9:00 p.m.

He wanted to be his old self again, playing the role of a younger and better Henock. Perhaps if I play the part well enough, he thought, some of it might actually rub off. He would clench his jaw, grind his teeth, and force his bad habits to go away, but he knew he had neither the will nor the anger to do it. He would never get his old self back.

10:07 p.m.

He was getting drunk now. He felt a yawn coming but sneezed instead. He left the table and went to the toilet. There was a mirror on one side of the wall where he saw his reflection. His heart skipped a beat—he didn’t realize that he had let his health decline this much. He felt the drunkenness leave him and he was stone-cold sober and alone—very much alone.

It was late when they left that night. Rachel was drunk and happy. Henock thought she was pleasant when she was drunk—it was the first time he had seen her drink. They reached his house and found more to drink. They were talking nonsense the entire time, blabbering and laughing about things requiring no real intelligence. Then they quarreled. She raised her voice to a crescendo and he dragged her to the bedroom, locking the door so that they wouldn’t disturb the neighbors. He expected her to cry but instead she made a lot of weird noises and rammed against the door, so he let her out. He begged, trying to cool her down, but she continued to sound like a trapped animal hammering its head against a crate. He was stupefied. I shouldn’t have made her drink, he thought. She started talking about how he was beginning to neglect her and how she thought he might have women on the side. He calmed her down after a lot of pleading, but when he got her to sit on the bed, she started all over again. She ran to the door and demanded to be let out. He thought of throwing a cup of cold tap water on her. When she picked up the bottle he wasn’t sure what she was going to do, but then she flung it and hit him on the head. It bounced against him like a billiard ball. He stood for a moment as though he didn’t know where he was, leaned against the wall, then advanced toward her. Rachel tried to evade him but he held her by the hair, twirled her, and knocked her against the wall. Rachel slid to the ground and started convulsing. He kept on kicking her while she lay writhing on the floor, a pitiable mess. He massaged the spot where the broken bottle had hit. She got up from the floor and dragged herself onto the bed, sobbing silently as she took off her clothes. When he called her to him, she sullenly obeyed; her hands and legs were like tendrils that were made to cling to him. She stopped crying when he started to respond to her. The bed was soft and submerged their bodies, and she whispered Jesus Christ into his ear every time she felt him coming closer to her. Once the seat had dried, she felt the cold like a splinter going through her bones. Henock was sleeping with his mouth agape. Careful not to wake him, Rachel gently pulled the blanket from under him and covered him so he could stay warm. Then she laid beside him, pulling his hand around her and squeezing it to bring herself closer. She ran her fingers over his chest that was covered by a smooth down of hair, counted his teeth, studied and kissed his hands. She prayed and cried a little before she finally went to sleep.

They were planning to wed in July after a number of similar scenes, but Rachel was too sick to be married then. She had tuberculosis, and she died in May.

10:20 p.m.

Henock stood and swayed while waiting to urinate—or was it after he was done? He could no longer trust his short-term memory. He stopped concerning himself with real people and even himself.

He suddenly remembered his friend who was fifteen or twenty years older than him and who liked to make cryptic remarks. They were friends a long time ago when he was young and foolish enough to believe that life would get better as he got older, that he would grow out of the darker days of his childhood. He had been young, arrogant, and gullible.

They had been watching a sick man who had all of the physical symptoms of disease, having lost all his hair. Their pity grew as the patient became completely engrossed with a morsel of something he was fighting to push down his throat.

“A mirror is a compassionate object reflecting false images the reflection wishes to believe,” his friend said. “If that man had watched himself from our vantage point, if he saw himself dining with his present condition, he would have thrown himself off a bridge and died. You can’t find out the truth about yourself until you come across your own self on the street, and then you observe yourself at a distance to decide what condition you are in.”

He returned from the bathroom to his table and tried to force himself to feel sleepy.

11:30 p.m.

There weren’t many people at the bar now, but the ones who were left made a great deal of noise. He lost count of the drinks. He didn’t notice the new drink that was brought to him. He feared that everyone would leave him alone, turn off the lights, forget about him, and lock him in as he remained wide-eyed and awake. When he paid, he felt as though that was the last money he would ever earn. He tipped the waiter well, and then he got up to go. His body was tired and broken—and all of a sudden he was falling. People laughed or didn’t notice as the waiter and bartender helped him up from under the table.

“Izohe! Izohe!” they said as they placed him on a chair.

He fell again outside in the darkened alley, where not a soul was about. He had no idea why his body and mind had contrived to take him through there. It was raining—first slowly, then hard. At some point he fell into a ditch, as though he had been heading straight toward it. He felt the rain on his face, and he had a memory of his niece, his distant niece.

There was something in his eye that made his vision blurry, and all the people, cars, and dogs he met on the street had a strange aura encompassing them like halos with multicolored lights.“You know what I enjoy doing best? I like walking through a heavy rain, and when I am soaked through I like to let go of my bladder. It doesn’t make a difference then because nobody notices, and I get to enjoy that freedom.”

12:03 a.m.

He was uncomfortable from the fall, and the rain struck him as if it were tiny pebbles. A part of his spirit that couldn’t stomach defeat, neglect, or surrender got up and fled for refuge somewhere else. What remained behind, inside of him, were a jumble of memories and a desire to sleep.

And those solitary midnight walks . . . On that lane facing the palace were the taverns where the off-duty soldiers came to drink and fornicate. And there was that one house with singers that played music on a keyboard and drew people from the street. The people inside would start fights and then be driven out by the waiters, and there was a man who sang for drinks and when he started to sing he would sober up, and because of his voice girls working next door would come in and everybody would be dancing alone when he sang, and he always sang something sad and the girls would dance close to the ground like they were mopping the floor. And he would keep walking outside until he saw the bon voyage sign at the end of the city, then go to work without sleeping. The truck drivers who delivered milk in the morning were his friends and would always stop for him and give him a lift back to town.

12:05 a.m.

He crawled out of the ditch and started walking in a new direction. There was something in his eye that made his vision blurry, and all the people, cars, and dogs he met on the street had a strange aura encompassing them like halos with multicolored lights. He vaguely sensed it was past midnight. He wore no watch, but he could tell the time by the way people around him behaved. In his eyes, people were like wound-up clocks that ticked toward destruction, and he could read them to tell the time. Usually, people tried to maintain a fake air of self- reliance early in the evenings that would wear out just before midnight. Cinderella’s charms of make-believe would quickly turn back into the original pumpkins and rats. He knew it was past midnight when his own attitude turned nastier. He would start picking fights or trying to grab street girls, and sometimes punches or rocks would start flying as the hours demanded it.

He kept a black-and-white photo hidden in his wallet. It was a shot of his parents. He was an only child. His parents met and married four years after he was born. His birth father was a scholar who’d left for India the same year his mother got pregnant and never returned. When he was five, his mother and his new stepfather were in a car accident, and neither of them survived. The photograph showed a young woman with a tall Afro and a miniskirt riding up to show shapely thighs. Beside her stood a man wearing horn-rimmed glasses and a smile. His grandmother had told him that he was also in that photo, because he was in the making, although there was nothing that indicated his mother was pregnant.

He grew up with his grandparents. He was quite attached to both of them—his mother’s father and his stepfather’s mother. They raised him and educated him, and they were not dead until after he’d left for Addis Ababa to study. He felt it was peculiar how they followed each other to the grave, only a year apart, as though they were a couple that wouldn’t survive without each other’s company, though they’d never really liked each other. He wasn’t there to bury them. He never knew how it all happened, or how it turned out. The blind old man died first, and the old lady followed. He remembered how he used to come from the field after a quarrel with the neighborhood boys, crying to tell somebody of his injustice, his pain. The old man would be sitting beside a tree. When he ran to him to spill his woes, shuddering and sniveling, the old man would listen, tilting his head to one side, his smallpox-blotted eyes moving back and forth. When he was done, the old man would laugh, waving the flies away, his teeth white and strong.

“Aye Abush!” he would say, reducing the whole tale to a joke. Then he would begin telling the boy a story he’d made up behind the closed windows of his soul. The boy would be too angry to listen to those stories then. The stories always had the same theme: the importance of unimportance, the utility of futility.

1:40 a.m.

He was walking on the paved road in the Bole suburbs now—a taxi had brought him there. He was wearing his soiled jacket, which he had to hold on his lap due to the driver’s insistence. After the taxi had turned and sped away, he’d walked slowly into an alley and could hear the dogs barking. He chose the house with a fence he could climb.

He had no way of knowing if the house had a zebenya or if the owner would take him for a burglar. He didn’t mind if he was caught—he was too tired to care and maybe even a little crazed enough to be fearless. He sat on the steps of the porch and waited until the neighborhood dogs stopped barking. He didn’t care if the proprietor of the house was in the vicinity or not. All he wanted was a moment without being interrupted. It was quiet and no light was coming from inside the house.

The rope was just the right length and strength. He imagined it had been used recently for skinning sheep, but he couldn’t be sure. He believed it was placed there, on the iron pole, waiting patiently for him to come and use it.He didn’t want to do it in a familiar place. The alcohol gave him the necessary courage and unreasonableness. He didn’t care about anything anymore—it was time for him to sleep. He was in such a hurry to get it over with that he didn’t even care about the consequences of breaking into a house. They could throw his body into a river for all he cared. All he wanted was to turn off the light and go to sleep. Besides, the light had not been great while it lasted. He wasn’t grateful for the light, he was bothered by it, and if he could, he would have turned it off permanently. Had he had some respect for the light, he would have gently blown out the candle, but he didn’t. He had no respect for anything at all, including himself, and he wanted to kick the switch and kill the light, in this strange midnight hour, in this strange unfamiliar neighborhood, inside somebody’s home he did not care to know. He decided here is where he wanted to sleep.

His head kept on replaying the sounds from his past, but he was helpless to drive these memories away. He couldn’t stand it, and he feared he might lose control over himself and start making noises.

The rain was still falling softly, but he was sweating. He searched around the house and found what he was looking for. The rope was just the right length and strength. He imagined it had been used recently for skinning sheep, but he couldn’t be sure. He believed it was placed there, on the iron pole, waiting patiently for him to come and use it. He took it down and gently made it into a noose. His hands were shaking but the tumult in his soul was ebbing, the rain that had been washing over his face tasting salty.

In the elementary school somebody referred to him as poor . . . and he broke their tooth with a rock. The next person who called him poor was a girl, and they were playing volleyball and he couldn’t hit the ball hard enough. He sweated his anger out and let it go. She was a girl, he told himself, and she was his first love. Later, he was disillusioned when he first saw her naked. She had big scars inside each of her thighs, like somebody had tried to stab her and had missed. She told him a dramatic story and he pretended he wasn’t interested, but in reality he was merely disillusioned because he’d thought she was immaculate and unblemished.

2 a.m. to 3 a.m.

He slept at length. It took, however, a long time to fall asleep, and none of it was pleasant. He felt as if he were an engine being turned on and then shut off, his body oscillating between two dramatic states of being.

Then he felt like he was being dragged out of his body, and while he would have liked to fly to the roof and toward the sky, he stayed until his body stopped kicking and became still.

It finally occurred to him while he was floating. It all became clear then, as he saw himself hanging on the high iron gate, a rope attaching him to one of the spikes.

It occurred to him that he was finally sleeping, resting.

There was no way of telling what might have happened if Rachel had not died so suddenly. He might have continued living even if he knew her death was caused by his neglect. Rachel had accepted her fate of loving Henock no matter what. The violent and unpleasant nights were her attempts to not accept this fact, thinking that escaping Henock meant escaping death. But something changed. Henock would have accepted her death if Rachel, after the struggles and tribulations, had finally given up on him. At last, she could stop loving him and go to the grave screaming curses and calling him names, just like she would do when they fought in the past. After she got sick, however, she had changed. Rachel had grown exceedingly silent and unapologetically loving. She stopped hiding her private feelings for Henock and would show affection openly. If she had feared that her feelings could spoil the relationship, that fear had completely disappeared. She would kiss his hands, which she’d never dared to do before unless he was fast asleep. After her illness, she started loving him all over again, this time softly. It was like receiving the love from a mother he never had. He’d had all kinds of experiences in life except being loved. Anger and distrust were the true parents who had raised him. What he gave to Rachel was the world he had grown up in.

Henock was not ready for someone like Rachel when he met her. She had already accepted her fate of loving him when he wasn’t even ready to accept himself.

Although he had spent his entire life with this trauma that had been mounting and suffocating him exponentially, he might have continued on if she were there. He would have lived alongside his multiple anguishes, drinking to oblivion, taking each day as it came. But after she died without his consent, something from the center of his soul drew the line. He had to give up, and he had no idea until his consciousness had punished him with sleeplessness. He didn’t think that time would run out, but in less than sixty hours, he faced the cruelest possible psychological deterioration: haunted by neighbors, chased by his own debacle of memories; devoured by his own guilt, then to be finished off with one final, dying wish of only wanting to sleep.

3 a.m. to 6 a.m.

He stayed hovering above his corpse until morning. He stayed not because he wanted to, but because he was anchored by some force and could not leave. He floated above the body and felt the coldness of it below him. The dogs kept barking and howling at the moon until morning.

It was the maid who first got up and found him. She was not the screaming kind, so she fainted.

9:50 a.m.

The police and the coroner were called. Nobody wanted nor dared to touch the body, so they made a provincial guard and another boy from the neighborhood carry him down. When the boy cut the rope, the body fell on him and he scrambled out from under it with a muffled scream. They helped the boy up, taking the rope from the corpse’s neck and throwing it away over the fence.

The top: the end, the base flat as a table and final as death.The moment they cut the noose he was free to go. Henock went up so quickly that he couldn’t tell how his body turned out or how they fought over the rope that was priceless in the black-magic market. The owner of the house couldn’t stop cursing as he turned the body over with his foot. The police officer dug into the corpse’s pockets and took out a wallet. It doesn’t contain any form of identification, the officer thought, but there’s plenty of money. The owner of the house cursed some more when he realized he had to spend the day explaining things at the police station.

10:06 a.m. (the end and beginning)

Henock went to the paramount zenith, with no sky having a limit, no star looking down from above it. The top: the end, the base flat as a table and final as death. Henock could look down at all there was and is, all below, all above.

__________________________________

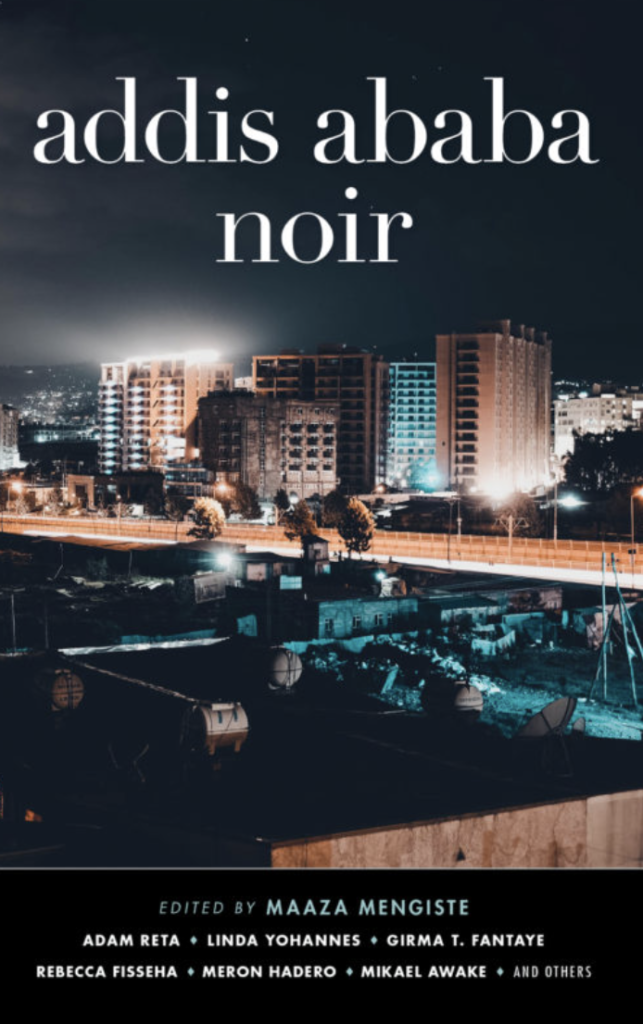

“Insomnia” by Lelissa Girma was originally published in Addis Ababa Noir, edited by Maaza Mengiste (August 2020). Used by permission of the author and Akashic Books.