Inside the Life and Struggle of Victorian-Era Women’s Rights Activist Annie Besant

Michael Meyer on an Overlooked Early Proponent of Reproductive Freedom in the United Kingdom

Westminster, June 23, 1880. We open at the Houses of Parliament, where on an otherwise uneventful early summer Wednesday, the prison room inside Big Ben’s clock tower holds two unrepentant rebels. One, the newly elected Liberal MP Charles Bradlaugh—age 46, tall, clean-shaven, with long grey locks combed back from his icebreaker brow—has refused to swear the required seat-taking oath that ends “so help me God.” When Midland laborers voted in Bradlaugh, they had also elected Parliament’s first professed atheist.

To rousing applause from the House of Commons’ green-leather benches, the Sergeant-at-Arms had marched the barrel-chested Bradlaugh—disparaged by Queen Victoria in a series of diary entries as “horrible,” “immoral,” and “repulsive looking”—up the clock tower stairs and into the smallest jail cell in the largest city in the world. But Victorian London, seat of an empire upon which the sun never sets, cannot cage Bradlaugh for long. Not with Annie Besant at his side.

Upon hearing the news of her confidant’s arrest, Besant—petite, chestnut-haired, 32, and still legally married to the abusive Anglican vicar she had walked out on seven years before—rushed in a one-shilling hansom cab from her rented house near Primrose Hill and down through the capital’s coke-flecked murk to the tower beside the Thames. The era is one of high Victorian politesse; the visitor is allowed to join the prisoner for supper.

In the cell’s high-ceilinged, oak-paneled sitting room—pulsing from the gallows-drop thud of Big Ben’s hammer and the bell’s reverberating E note—Annie Besant plots their next move. Once again, the pair are up against Church and Crown. Once again, Bradlaugh counts on Besant to take the lead. Not for nothing would a smitten George Bernard Shaw once marvel: “There has never been an orator to touch her.”

Annie Besant had thrown herself into public life in the same manner that Big Ben announces the hours: loudly, and with a resonance that can still be felt today.

In an era when British society could not have been more gendered—men sporting bushy sideburns known as Piccadilly Weepers, bonneted women squeezing their crinolines sidelong through doorways—Annie Besant had thrown herself into public life in the same manner that Big Ben announces the hours: loudly, and with a resonance that can still be felt today.

This is not the first time that Besant and Bradlaugh have shared a cell. Three years before, City of London constables had arrested the duo for publishing and selling the first popular birth control manual. Called Fruits of Philosophy, the American doctor Charles Knowlton’s pathbreaking booklet put safe methods of “checking” pregnancy in the hands of women, and argued that reproductive health should be frankly discussed in physiological, rather than moral, terms. Annie had priced her reprint of the pamphlet’s pulpy pages at sixpence to better reach the working-class men and women packing the terraced brick lowlands of London’s East End.

Besant and her partner Bradlaugh’s crime, officially, was obscenity. The sensational trial that followed dragged debate over sex, censorship, marriage and morality onto the front pages of newspapers gracing breakfast and dinner tables across the United Kingdom. The coverage spawned more coverage; a prosecution meant to silence insubordinate voices instead broadcast them further than ever before.

Nothing like it had ever happened, and the proceedings took place on a stage that would not be seen again. Trimmed in ermine and wigged with horsehair, Britain’s highest judge had moved the proceedings to the palatial splendor of the Court of Queen’s Bench. The since-razed courtroom was attached to hallowed Westminster Hall; the sounds of Big Ben and the bells of Westminster Abbey seeped through its soot-stained, sandy limestone walls. Here, at the very heart of the British Establishment, Annie Besant had bravely asserted a woman’s right to bodily autonomy.

“It will be no exaggeration of Mrs. Besant’s speeches,” Charles Bradlaugh wrote after the verdict, “to say that they are unparalleled in the history of English trials.”

Until then few men, and no women, had dared to publicly advocate for, let alone teach, sexual education and safe methods of birth control. (The latter term would be coined decades later in the United States by Margaret Sanger, who, like her British counterpart Marie Stopes, had yet to even be born when Annie Besant stood in the dock.) In a century scored by steaming, clanging, sparking progress—hear the trains, feel the blast furnaces, smell that smoke—the teaching or sale of contraception not only remained socially taboo, but also became technically illegal. While birth control remains a contentious subject today, in the Victorian era, as one journalist later put it, open discussion about sex and reproductive health “was not even controversial. It was nothing but asterisks.”

Annie Besant not only spoke and spelled out shushed and censored ideas, but willingly courted her prosecution as a test case. “If we go down in this struggle,” she wrote after her arrest, “there are many London publishers who, when their turn comes, will regret that they failed to do their duty at this crisis.”

She chose active over passive resistance. “So many people boast on the platform of what they are going to do,” she continued, “and then quietly subside when the time for doing comes, that it seems to startle them when platform speeches are translated into deeds. Falstaff is so easy a character for an actor to play.”

Besant felt the kingly duty to lead. “We do not want our libraries to be chosen for us by detectives,” she asserted, “nor do we intend to acknowledge that [the Crown] is the best judge as to what we may read. A very decided stop must be put to this tyrannical interference with our rights.”

The worst that could happen to her, she claimed, were fines and prison. But as a near-bankrupt single mother estranged from a rapacious husband itching to seize custody of their children, Annie Besant knew that a guilty verdict would mean so much more.

For decorum’s sake, she was the only woman allowed to attend her own trial. The adage holds that anyone who acts as their own lawyer has a fool for a client (and a jackass for an attorney), but still Besant and Bradlaugh opted to represent themselves, using the courtroom as a megaphone. Forty-five years before Helena Normanton became the first British woman allowed to be called to the bar and practice as a barrister, the novice Annie Besant stood in a courtroom packed with lofty men—judge and jury, prosecutors and press—and eloquently made the case against book banning, and for the free discussion of contraception and a woman’s right to its use.

“We have not the smallest intention of posing as meek and melancholy,” she promised. “We well know that if we can upset the proceedings, our enemies will think twice before they begin again, and we shall probably go on our way undisturbed, and the right to discuss will have been made…To lose all, save honour, is better than to lose honour and gain all.” The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant made her one of Britain’s most famous women, surpassing Florence Nightingale, and coming in second only to her nominal prosecutor, Queen Victoria. Emerging from a Miss Havisham-like decade of mourning for her late husband, Prince Albert, Her Majesty’s fortieth year on the throne had begun fortuitously, when on New Year’s Day in 1877 the Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had finally overcome parliamentary opposition to proclaim her the Empress of India.

By this time, Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh were as inseparable as the widowed queen and her Scottish servant, John Brown. But unlike Victoria, who relished signing her letters “R & I”—Regina et Imperatrix, Queen and Empress—Besant was a common married woman. Her own embossed stationary may have showed her motto “Be strong,” but by law she was weak, with the same rights as a dependent child—only without the possibility of escaping the home upon maturity. A British wife was chattel, subservient to her husband’s desires and expected to be a tender mother and spotless wife. Coverture laws forbade her to own property, sign contracts, keep her own salary, maintain custody of her children, or love on her own terms.

After rejecting marriage in favor of nursing, but before making her name in the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale had wondered “Why have women passion, intellect, moral activity, and a place in society where no one of the three can be exercised?” A quarter-century later, Annie Besant seized that place for herself in the seat of the world’s largest empire. In an unpublished memoir donated to the British Library, her niece Freda Fisher—writing 50 years after the trial, when, among other rights, women could vote, strike, divorce and be economically autonomous—realized that “A large portion of the history of female emancipation is bound up in the story of her doings.” The journey extracted many tolls. “The bill my aunt paid for her independence,” Fisher wrote, “was a very heavy one.”

After her prosecution and, three years later, her dinner with Charles Bradlaugh in the prison cell below Big Ben, the hands of Annie Besant’s own life-clock will sweep across nearly every major political and intellectual movement of her time. In addition to leading the vanguard in the long march for reproductive rights, she will preach, organize, and—at the first “Bloody Sunday”—bleed for suffragism, fair pay, meals for malnourished schoolchildren, religious freedom, and the independence of colonial Ireland and India.

Her agitation against the Raj (though not her trailblazing trial or promulgation of birth control) will be remembered with Indian street names, postage stamps and even, in 2020, a Coast Guard patrol ship launched as the Annie Besant. Mahatma Gandhi will admire her “amazing energy and courage,” and never forget “the inspiration I drew from her in my boyhood.” The Mahatma, like George Bernard Shaw and nearly every other friend and fellow fighter with whom Besant will forcefully fall out, will remain magnanimous to the end. Long after their courtship crashed, the future Nobel laureate in literature will write her into his plays as the strongest woman on his stage.

Her closest confederate, Charles Bradlaugh, will not take their own split so well.

But that fissure, so unthinkable as their tea is poured in Parliament’s prison on this mild June night in 1880, remains in the future tense. As does the short cul-de-sac in London’s East End named Annie Besant Close, and the small plaque in Spitalfields noting the building’s pre-gentrified life as the location where Annie Besant helped found the British Trade Unions. Such paltry memorials would not surprise Virginia Woolf, who, after surveying the shelf of gendered biographies recording Britain’s nineteenth century, concluded, “The Victorian age, to hazard [a] generalization, was the age of the professional man.”

In our more equitably enlightened times, Annie Besant’s pioneering advocacy remains overshadowed by her erstwhile allies. In Northampton, the base of the towering statue of Charles Bradlaugh recalls him as “A sincere friend of the people. His life was devoted to progress, liberty, and justice.” From his perch atop a busy roundabout, today he looks devoted to directing traffic. Up Earl Street at the busy Charles Bradlaugh pub, a framed lithograph depicting his arrest in the House of Commons hangs on the wall back by the toilets. The owner and bar staff draw a blank when asked what they know about Annie Besant, and their trial over birth control.

Her name does not appear once in the door-stopping two volumes of the Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750–1950, even as its pages note, without surmising a reason (which could be legion), that the nation’s birth rate was halved, to three children per couple, in the years starting from 1877.

That happened to be the year when Annie Besant first popularized contraception in print.

In London’s Parliament Square, you won’t find her name among the 59 early supporters of women’s suffrage chiseled onto the plinth of Millicent Fawcett’s statue. Nor is she among the 75 names carved onto the Reformer’s Memorial, the Victorian activist roll of honor standing tall in the capital’s Kensal Green Cemetery. The granite obelisk has room to add her, too; one blank space remains beneath the likes of Charles Bradlaugh, William Morris, Robert Owen, Lydia Becker, Harriet Martineau, Mary Carpenter and Henry Fawcett, the Liberal MP who in 1877 had shamefully dodged Besant’s summons to testify on her behalf.

In 2022, English Heritage—”We bring the story of England to life”—replaced an unofficial marker commemorating Annie’s role in London’s Matchgirls’ Strike of 1888 with an official one that omits her name. The old sign’s outline remains stained into the red brick wall; as with her life, if you know where to look, you can see her trace, still. Besant’s lone Blue Plaque, affixed to the white stucco bungalow she briefly rented near the Crystal Palace in south London after fleeing her husband, curtly sums her up in two words: “Social Reformer.” Which, if you know the totality of her achievements, is a bit like defining Victoria as merely “A Queen.”

Far ahead of her time, Annie Besant foresaw that reproductive rights were worth fighting for, codifying in law, and unceasingly defending.

The past does not fit neatly into memory, let alone onto a plaque. But like that official marker—cloaked by overgrown vines at 39 Colby Road in a city where only 14 per cent of its Blue Plaques celebrate women—Annie Besant hasn’t been written out of history so much as obscured by it. You can sometimes spot her in the thick tomes surveying the Victorian era, although her fleeting appearance on a page or two—a fraction of Bradlaugh’s mentions—usually belies her outsized, if correct, depiction as “the leading female radical and secularist” and “the mirror of her age.” In these tellings, Besant wasn’t born so much as hatched. And just as soon as she enters the story—cue the “sex radical”—she’s gone, never to return.

You know it’s time to write a book when the one you want to read doesn’t exist. The seeds of this one were planted after taking a wrong turn passing through Northampton one hot summer day, and wondering why the town had erected a statue to Marlon Brando, looking leaner and taller but simmering, even in stone, with purposeful intensity. Who was Brando’s Victorian lookalike, Charles Bradlaugh? More interestingly—turn the smartphone screen from the sunlight’s glare, and keep clicking link after link—who was his “close associate” Annie Besant?

A badass. A battering ram. A woman who braved the opprobrium and stones (actual stones!) hurled at her, inspiring the next generation of social reformers and suffragists. No matter one’s politics, who among us would not want to live so bold? This story focuses on the decade-plus when this unhappy housewife of a clergyman took aim at and subverted such seemingly intractable Victorian tenets as the Church, marriage, sex, class and imperialism. Rather than waiting for change to happen, the audacious Annie Besant had liberated herself.

Her partner Charles Bradlaugh’s arrest for violating the Obscene Publications Act was the next in a line of dogged acts of civil disobedience that endeared him to the Northampton electorate who would send him to Parliament—and into the clock tower prison cell. But for a 29-year-old single mother of two young children with no savings and a reputation as a radical, this defiance was everything. As a woman, Annie Besant had far more to lose.

Outwardly, she didn’t flinch. Uniquely, we can hear her story largely in her own words. Fifty years before Virginia Woolf argued that a female writer needed “a room of her own,” Annie Besant owned her own press and publishing company. Unlike most accused criminals shuffling mutely into court or jail and off the page, she recorded the run-up to her arrest, the trial and its aftermath in a series of unabashed columns, pamphlets, and a searing memoir, which—for reasons that will become clear—she later decided to pulp.

Far ahead of her time, Annie Besant foresaw that reproductive rights were worth fighting for, codifying in law, and unceasingly defending. Across the years, her voice still rings as clearly as Big Ben. Birth control remains the most cost-effective intervention in health care, just as access to it remains under threat.

“By this time next week I shall be on my trial,” Annie wrote in June 1877. “One word only I say in conclusion: Let the verdict be what it may, my mind is made up….Come what may, this battle must be won, and, having taken up the sword, I will not lay it down again until the victory is won.”

Her 12 special jurors (of course, all male) had been drawn from the Establishment she sought to subvert. They lived in smart London townhouses that subscribed not to Bradlaugh and Besant’s small, secularist and republican weekly the National Reformer, but to the staid daily Times of London, whose readers supported the primacy of Church and Crown.

To scoop his competition (19 other morning London papers, and 9 evening ones) The Times ’ owner ordered his son and heir apparent to serve on the jury as its foreman. The Establishment’s mouthpiece would have a front seat for The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant. Initially, however, the paper, like the rest of the British press, did not realize the public’s piqued interest in the case, and in its defendants. One defendant, in particular. A woman, standing in the centre of political power, asserting her right to educate, to speak freely, to choose.

No prison cell, or judge, or jury sitting beneath a tolling Big Ben could silence her. Turn those storied clock hands back to 1877; the end of the old world has just begun.

__________________________________

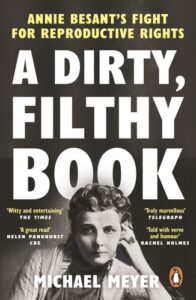

From A Dirty, Filthy Book: Annie Besant’s Fight for Reproductive Rights by Michael Meyer. Copyright © 2025. Available from Penguin Books UK, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Michael Meyer

Michael Meyer is a critically-acclaimed author and journalist who has written for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and many other outlets. A Fulbright scholar, Guggenheim fellow, Berlin Prize and Whiting Award winner, Meyer has also received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Cullman Center, MacDowell, and the University of Oxford's Centre for Life-Writing. He is a Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh, where he teaches nonfiction writing.