By the time the US edition of Deadly Quiet City: True Stories from Wuhan arrives in the bookstores, the world will have returned to some semblance of normality. Most people will be able to walk the streets, go to work, study, and visit relatives without the constant fear of COVID-19.

The only exception will be China. A country of over 1.3 billion people will have suffered under rolling lockdowns for over three years—and the lockdowns will continue. Many people in China believe the virus is still deadly and spreading unstoppably around the world. Therefore, under no circumstances can China relax the controls. “Even in an advanced country like America, over a million people have died,” said a friend in Beijing a few months ago. “Look at China. How many people will die if we slack off like America?”

My friend is not uninformed or prejudiced. He is simply making the same mistake that many Chinese people make—he believes the government. Over the past three years, the government has been incessantly repeating its narrative: “The world is very dangerous, and you should thank us for protecting you.” Like children trapped in a cave, 1.3 billion citizens hear a wild beast howling outside the cave and they tremble in fear. Few stand up and ask what is really happening outside. If they do, in no time at all they will end up in an even darker and more confining cave.

This is in no sense benevolent, but the government is clearly benefitting a great deal. It took very little time for Xi Jinping to succeed in getting a third term. For many years to come, the Chinese people will have no choice but to submit themselves to his oppressive rule. Like leeks waiting to be harvested, as they say in China, an idiomatic phrase for suckers about to lose everything to a crooked stock manipulator.

How did China—once the factory of the world, the world’s second largest market with countless skyscrapers and highways—come to this?In prosperous megacities like Shanghai, or in remote mountain hamlets, people are forced at any time into a “state of silence,” which means no timely medical care, no leaving home to buy food, in fact no leaving home at all, like fish unable to escape the tanks at a fish monger’s shop. For those who dare to break the rules, officers in full PPE will appear as soon as anyone pipes up. They will have no compunction about assaulting violators, or even tying them to a tree for public humiliation.

Many people have heard the dreaded midnight knock on the door. It means there are infections in their neighborhood, or in their city. Just one case is enough, even an asymptomatic case, to implicate the whole neighborhood, or the whole city. Hundreds of thousands of people have been woken by the midnight knock. Infants in swaddling and the elderly with serious illnesses are forced to leave their homes. Enduring bone-chilling winters, sweltering summers, and torrential rain, parents carry children as they support the sick and elderly, and stumble to the buses that officers allocate them to, like merchandise or livestock, destined for tightly guarded isolation centers—let’s call them concentration camps.

On this vast land from Shanghai in the east to Guiyang in the southwest, hundreds of millions of Chinese people must report their location and status to the government like criminals on parole. Everyone has a personal QR code which is required to prove you are legal and uninfected just to be able to take subway journeys, enter restaurants, or shop at supermarkets. No one cares anymore about privacy or rights because they disappeared long ago in China.

In the foreseeable future, COVID-19 prevention policies that treat people with contempt will continue. When the day comes that COVID-19 is no longer a pandemic, Xi Jinping will not relinquish ruling by QR code. It will shackle China for a long time to come because the QR codes report people’s movements; and when required it can be changed to ensure that “petitioners” and dissidents, as well house church congregants, have no options to seek justice. This is an advanced technology for controlling people that even George Orwell never imagined.

Every few days, uncomplaining “QR code citizens” line up at booths inside which there is a person, or sometimes a robot. They then squat down, open their mouths, and wait for the person, or the robot, to stick a swab down their throats or up their noses just to obtain a “nucleic acid test visa” valid for one or two days. Only then can they legally leave their homes. But very soon they will need to apply for a new certificate, and then another and another. There will be no end to it all. If you forget to visit the testing booth, you will be reprimanded. If you try to evade testing, just wait: soon enough law enforcement officers in PPE looking like astronauts will knock on your door.

Strewn along this humiliating road lie far too many corpses. Infirm elderly have committed suicide because they cannot get medical attention; unemployed youth have leaped from buildings in desperation; unborn children have died in the wombs of mothers waiting for clearance to enter maternity wards. In the early hours of 18 September 2022, a bus full of people heading to an isolation facility crashed off the road resulting in twenty-seven deaths. Before they were taken from their homes and shoved onto that bus, they were just like us. They had dreams, unpaid debts, favorite restaurants, and loved ones…but because they lived in China under a totalitarian rule, they were forced to leave their homes, board a bus, and die tragically at the bottom of a ravine.

Since the accident, people selected for transportation to isolation facilities are required to sign a declaration. The wording is usually abstruse, but the gist is always the same: I agree to being put into isolation and if I die, it is nothing to do with the government.

“I wonder, if I had been in the same building, how would I have avoided death,” an author posted online. “Could I have avoided being sent to the isolation facility? Could I have avoided getting on that bus? Would I have had the courage to stand up and oppose the absurd policy?” I ask myself these questions over and over, but the answer is always, no. If I refuse to go, they will arrest me. If I stand up in opposition, they will torment my family and my children. So I have no choice other than obedience. I will obediently leave home, I will obediently get on the bus, and I will obediently hurtle to my death.

“This is my fate. But, my friends, this is not just my fate alone.”

The post disappeared in a few minutes. Perhaps the author was warned or perhaps the indefatigable censors perceived some danger and deleted the post, “according to the law.” But the author’s questions will not disappear. They await answers. How did China—once the factory of the world, the world’s second largest market with countless skyscrapers and highways—come to this? What opportunities did we miss as we slid down into this abyss? Could we have rolled up our sleeves and shouted “No!” at the dictator and saved that bus from hurtling over the cliff? And at this moment when the dictator has pushed all of China into the doomed bus, could the world do anything to save the millions of families on the bus?

*

The COVID-19 catastrophe delivers a sober lesson. We should not forget it was the Chinese government’s deliberate coverup and misleading information that caused an epidemic in Wuhan to spread rapidly around the world. Nor should we forget that the same government’s refusal to openly investigate the origins of the virus caused its provenance to become an unsolvable mystery. To this day, we do not know how it started and how it spread to humans. And we may never know.

After all this, how does the world see this dishonest and irresponsible government? When the Chinese government next ratifies a treaty or signs an agreement, will it fulfill its obligations? Are the Chinese government’s promises believable? If there is another disaster like COVID-19, will the Chinese government behave honestly and responsibly? This book cannot answer these questions, but I hope it will inspire deep reflection.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus began in the city of Wuhan. From space, cities look like anthills from which each day multitudes of tiny figures emerge and disperse just like busy little worker ants. The roads are crowded with little metal boxes in which they move, making a disconcerting racket. At dusk, lights come alive in an array of bright colors and stay on all night, illustrating the magnificent civilization humankind has created. But in the spring of 2020, in a large city in the south-eastern corner of the Asian landmass, an entirely different scene appeared. The tiny creatures and little metal boxes disappeared, and all that remained was row upon row of silent structures. The once-vibrant streets were now empty and quiet.

On 23 January 2020, Xi Jinping personally ordered the city of eleven million be placed in total lockdown. All transportation links were cut, leaving millions trapped inside their own homes. During the seventy-six-day lockdown many people died silently; those who survived were tormented by fear day and night. They were anxious, frightened, and angry. They wailed plaintively for food and medicine, but hardly anyone on the outside heard them. No one knew what the millions of “inmates” were going through and how they lived inside this catastrophe.

In my book, I sought to take the reader inside the city during lockdown and introduce them to the people whose voices were drowned out by the blaring official narrative. Here, they will tell their own stories.

I must admit that gathering the stories was no easy task. In China, searching for the truth can often be a criminal offense. Others went to Wuhan before me, at the most dangerous and difficult time, and we must remember their names: Fang Bin, Chen Qiushi, Li Zehua, Zhang Zhan. These citizen journalists tried everything in their quest for the truth, but all were soon arrested and silenced.

In China, searching for the truth can often be a criminal offense.While I was in Wuhan, I often thought, “what has happened to them could happen to me”—held in a gloomy dungeon with no sunlight, locked up alone, constantly interrogated and subjected to torture and cruel treatment, then escorted to a court to hear an imposing judge proclaim my crimes. It’s a terrifying scene but not uncommon. In the past eight years, thirty-six friends of mine have been arrested. They are lawyers, journalists, and professors, all kind and honest people who have become enemies of the state simply because they have said something the government doesn’t like.

I have said the same sorts of things. Before Xi Jinping came to power, I was a bestselling author. Then, because of what I wrote, all my writings were prohibited from being published and all my social media accounts were closed to my millions of followers. I became a criminal suspect, someone to be watched. The secret police would frequently come to my door. Sometimes they were polite, sometimes fierce. They forbade me from participating in certain activities and forced me to delete things I had written.

Sometimes they threatened me with violence. “You’re puny,” one secret policeman said with a malevolent chuckle. “How much beating can you take?” One freezing night not long before the novel coronavirus epidemic took hold, two policemen pounded on my door and took me to a police station. The interrogation lasted for hours, and they took detailed notes. One of them repeatedly threatened to haul me off to a detention centre. I thought I was psychologically prepared, but at that moment I discovered I would in fact tremble in fear.

You can say that my book is a book about fear. I was in fear when I arrived in Wuhan, and I was in fear as I sought the truth and interviewed people. I was in fear as I wrote. Prior to publication I fled my country in fear, with all my belongings in just one suitcase. I left behind everything I had built and accumulated in my forty-seven years. I am now sitting in a coffee shop in the north of London, out of their reach, but I admit that when I recall all those times of trembling over the previous year, I still feel the heart-sinking, bitter taste of terror.

*

When the epidemic exploded, I had no thoughts of going to Wuhan. At that time, I was living in a small apartment beyond Beijing’s fifth ring road. Over the course of two months, I had only gone outside three times. Like all panic-stricken Chinese people, I was frightened of being infected, though I was even more afraid of the Chinese government’s epidemic prevention measures—the cutting of transportation links, the limits on movement of people, and the blocking of information. Few others were concerned about the lost freedoms and those who were dared not voice their opinions.

My neighborhood did not have a single case of coronavirus, yet the local government still put up a fence with only one point of entry. Every time I left, I had to show the guards a small red card—my exit pass and permit to return home. Outside the fence, on the broad avenues of Beijing, there were virtually no cars or pedestrians. The traffic lights changed color in solitude and flowers blossomed unnoticed.

I had never seen Beijing look like that before. I wondered what ground zero of the disaster might look like, 1200 kilometers away in Wuhan.

On 3 April 2020, I received a telephone call from Professor Clive Hamilton, a person I have long held in high esteem. He asked me where I was. I answered, Beijing. He sounded a little surprised. “You’re not in Wuhan?”

His question came out of the blue, but it had the effect of a sibylline enlightenment. I was momentarily stunned. I thought to myself, “That’s right. Why am I not in Wuhan?”

After Clive’s phone call, I instantly saw the path forward. I knew I had to go to the locked-down city to find people who had been cut off from the world and learn about their lives to tell their stories. “This is something you must do,” I told myself. “Just do it, and do not think too much about the consequences.”

That afternoon, I went to a remote place on the outskirts of the city and had a long conversation with a close friend. We briefly discussed the possible dangers of the journey. My friend taught me how to set up a secure email account and how to transfer materials safely. Most importantly, my friend warned me sternly, “Don’t tell a single soul!”

I bought a train ticket, booked a hotel in Wuhan, and purchased lots of masks and sanitizer. At noon on 6 April, I quietly made my way to the train station. I kept my head down to avoid making eye contact with anyone and to evade the ubiquitous surveillance cameras. I boarded an empty train carriage like an explorer entering a dark cave, unsure what they would find.

All the way to Wuhan, no one else came into my carriage. It felt miraculous; on hundreds of trips in the past, every single train was crowded and noisy. I had never thought that a Chinese train could be so empty and so peaceful.

As I was enjoying the journey undisturbed, albeit with a sense of foreboding, my phone rang. The number was unfamiliar, and I tensed up. I have received countless calls like this and know the procedure well. I didn’t answer, watching it ring until it fell silent. After a few minutes the same number called again, but this time the caller gave up impatiently after a few rings. I used another telephone to share a photograph of the screen with a friend. I commented, “In China, we are all transparent. They know everything.”

By “they” I meant China’s secret police. I sometimes call them customer service officers. There doesn’t seem to be anything they don’t know. It was quite possible they had been following my movements and that my caution and care had been in vain. Perhaps they were laughing at my measures to avoid detection. By the same token, I was quite clear-eyed; a telephone call like that should not be ignored as it would provoke even more serious consequences. At the time I thought, “Whatever is coming will arrive sooner or later; so be it.”

During my time in Wuhan, I was always on edge. I stayed at the five-star Wuhan Jin Jiang International Hotel on Xinhua Road, one of the few still open. Most of the interviews for the book were conducted in my hotel room, though on certain occasions I walked to a place by the riverbank late at night, or to a quiet street with no one else around.

Late one night, as I was going through the day’s interviews, I suddenly heard voices softly talking in the corridor. Immediately, I was on my guard. I stood up, switched off the lights, and crept gingerly towards the door. I peered through the peephole looking for activity in the corridor. I saw nothing but couldn’t stop feeling anxious. I frequently got up in the dark to look again at the tranquil corridor. At one moment I imagined they were about to burst through my door, which sent my heart racing. After half an hour or so I calmed down but the palms of my hands were drenched in sweat.

I was overreacting, but not without reason. Before Fang Bin disappeared, he posted a video clip on social media in which he shouted to his followers, “They’re nearby.” The young citizen journalist Li Zehua was arrested while live streaming on social media. His last words were, “I’m being raided. I’m being raided.” Then the live stream abruptly went dead. On that chilly spring evening as I peered nervously into the darkness, I saw Fang Bin and Li Zehua. I saw their faces and their fates, and I saw myself there too.

In that same hotel room, a deeply worried Yang Min, a mother who lost her daughter, asked me, “Is this room bugged?” I had the same misgivings. I often felt I was being followed, surveilled, and eavesdropped on; it may not have been the reality, but I couldn’t prevent myself from thinking that way. All I could do was back up everything.

After each interview, the first thing I did was pass the materials on to a friend abroad. When we discussed the project, I repeatedly emphasized: “If I am arrested, please give the materials to Clive and he will complete the book.” Publication in the West would make my life more miserable in jail, but I also knew the bad days would one day be over, no matter how wretched they might be. I thought, I’m still young enough to cope.

Few others were concerned about the lost freedoms and those who were dared not voice their opinions.When friends phoned to see how I was faring, I sometimes hid under a blanket and spoke softly so as not to be snatched by the wild beast roaming about outside. I avoided talking about current affairs because it was dangerous; at most I talked about food or the weather. I would tell my friends enthusiastically, “I’m writing a science fiction novel.” It was a lie, and a laughable one at that, but it was not entirely untrue. Some of the scenes in this book are so surreal they really do belong in a sci-fi novel.

Not everyone agreed to be interviewed. One local official said to me, “I’m sorry, I must adhere to the regulations which prohibit interviews.” A doctor at a big hospital, whom I had telephoned several times in the hope he would talk to me, initially said he would “think about it.” A few days later he politely turned me down.

In that interminable spring, the doctor continued to work while ill; he too was infected with the coronavirus. He must have seen bodies and perhaps shed many tears. He certainly yearned to tell someone what was on his mind but, for reasons he was afraid to reveal, he preferred to bury everything deep in his heart. “Brother,” he said, “I thought about it long and hard but let’s just forget it. I hope you can understand it really isn’t convenient.”

I said to him, “I completely understand. I just hope that one day you will be able to tell me everything about your experience, your feelings, and what you saw and heard.”

He went silent. “I hope so too,” he replied softly.

Fear is cumulative. Especially in 2020 in Wuhan. The longer I stayed, the sharper the fear became.

My hasty departure from the city was triggered by another mysterious phone call. On 4 May, a man with a Beijing accent asked me point blank, “What are you doing in Wuhan?” I replied that I was just looking about, for no particular reason. “Then you’d better be very careful,” the man said, sounding deeply concerned. “You don’t want to get infected because that wouldn’t be good.”

To this day, I do not know what that phone call meant. Perhaps he was genuinely concerned for me, or perhaps it was another kind of warning: “We know where you are, and we know what you’re doing.”

I still had plans. I hoped to take another look at the virus laboratory; I wanted to interview many more people. At the time, Zhang Zhan was planning to help the families of coronavirus victims seek justice; I thought I could observe her and record her activities. But the mysterious phone call forced me to rethink my plans. I had already interviewed more than a dozen people and recorded more than a million words. This was my burden. The more people I interviewed, the heavier the burden became. I didn’t want to risk all that.

I worked anxiously for another two days. I bought a train ticket for 7 May, traveling first to Yueyang on the opposite bank of the Yangtze River. I did not return to Beijing; with all the surveillance, it would be too risky to work on the book there. Instead, I flew to Sichuan, a mountainous province, and continued to write this dangerous book in a small town deep in the mountains.

Eight days later Zhang Zhan was arrested.

It took me ten months to write this book because there were many interruptions, the first after Zhang Zhan’s arrest. The police questioned many people who had been in touch with her. A friend sent me a photo of a get-together I’d attended in early May, warning that everyone in the photograph had been questioned and that I was probably next.

I hung up the phone and stared in a daze at my draft on the computer screen. What if something happens? What a pity it would be if I were unable to complete my task. Give me more time so I can finish it.

There were two more mysterious phone calls, one in November 2020 and another in January 2021. Two different men called, and their tone was mild, as if they wanted to have a casual chat or send a greeting. But I was panic-stricken. After each of those calls, I put the material in a safe place, deleted everything on my computer, and waited in silence for a visitor. No one came. Perhaps the secret police were afraid of being infected.

I completed the draft in March 2021 and handed it over to my friend. The last words I wrote were: “No matter what happens to me, this book must be published.”

My loyal friend replied: “Understood.”

__________________________________

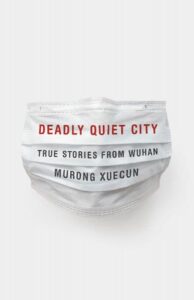

This excerpt originally appeared in Deadly Quiet City: True Stories from Wuhan by Murong Xuecun, published by The New Press. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted here with permission.