My grandmother and her four brothers came to America to escape poverty and—for her brothers—the threat of being drafted into the Russian army. At that time, Finland was ruled by Russia. The America to which they immigrated was not a land of milk and honey. It was a land of potential milk and honey, the realization of which took enormous hard work under horrible and dangerous working conditions and fights, sometimes literally to the death, between labor and owners.

Simply surviving was an act of heroism. The immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries—the Irish, the Italians, the Finns and Scandinavians—faced the same issues we are dealing with today: fear of change and xenophobia on the part of those who had immigrated here earlier; horrible income inequality; the struggle to secure a living wage; rigid class structures; a nation divided by class and culture; and feckless politicians, unable to unite the nation other than under the banner of war.

My Finnish grandmother, Ina Silverberg, was born in Kaustinen, Finland in 1889 and immigrated to America when she was 16. She was a communist who proudly read the Daily Worker until it endorsed the Russians in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. This, she said, was the last straw. She worked as a cook in the logging camps, as a fish-cleaner and packer in the salmon-packing canneries in Astoria, Oregon, and was an active-but-low-level member of the IWW, the Industrial Workers of the World.

Ina had four brothers, who all came to America around the turn of the 20th century. Three of them carved adjacent farms out of the forest on the north bank of the Naselle River, my inspiration for the Deep River in the novel. I spent many boyhood summers on those farms. All my great-uncles also logged. The one who didn’t farm, eventually owned a small logging company.

The initial impulse to write Deep River came from waking up one night with an image of my grandmother looking out at the Columbia River through the living-room window of her house in Astoria, Oregon. The river is five miles wide at that point. On the near shore was the abandoned pier where my grandfather had moored his fishing boat and mended his nets. On the far shore were the hills, once covered in old-growth forest, that hid the small valley where she and her brothers first farmed when they came to America from Finland. I was struck that night with the pride she must have felt, looking from the window of her modern ranch-style house, paid for by much hard work and sacrifice. I also understood how she must have missed not only my grandfather, but the time of her youth, when they danced Saturday nights in the net sheds, when the salmon were close to the size of men, and the old-growth trees, even laying on the ground, were still two or three times the height of the men who felled them.

I imagined that she was looking at the great river, feeling the sadness of the passing of her culture and language as her generation passed away, the world of her youth transformed by technology and urban sprawl, the old growth forests gone. Her generation was heroic, but it was not innocent. This image became Deep River’s final scene.

My biological grandfather, Leif Erickson, (it would be difficult to find a more Norwegian name) was a gifted storyteller. He loved reciting poetry from memory, in his native Norwegian, as well as in Finnish and English. He also spoke Swedish but refused to use it after Sweden betrayed Norway by aiding the Germans during World War II. Leif was illiterate. He went to work in the woods at the age of eight as a whistle punk to help support his family. Despite his illiteracy, he had a gifted mechanical mind and eventually worked his way up to become a renowned logging railroad locomotive engineer. This was one of the most prestigious jobs in the woods.

I imagined her looking at the great river, feeling the sadness of the passing of her culture and language as her generation passed away, the world of her youth transformed by technology and urban sprawl, the old growth forests gone. Her generation was heroic, but it was not innocent.We thought that our step-grandfather, Axel Silverberg, was our true grandfather. Axel was a gill-netter who had an extraordinary skill in finding the salmon. He was often top boat on the river in terms of fish tonnage. I worked for him as a teenager, paid a small percentage of the gross. Many times, I would watch amused as Axel tried to ditch other gill-netters who were tagging behind us after we’d pull up the net to seek fish elsewhere. When the salmon weren’t running, Aksel logged and worked the log booms. Aksel was also a very fine dancer, as was my grandmother, and they danced nearly every Saturday night at Suomi Hall, the home of the Finnish Brotherhood, in Astoria.

The novel has many strong female characters, influenced by my great-aunts and my grandmother’s friends, all stalwart, hard-working women. They mended nets, often together, watching for their husbands’ boats, always aware that maybe this time there would be no returning boat—and it happened often. Whenever the church bells started tolling, the women whose husbands or sons worked in the woods would stop, listen, and then wait with fear and hope in their hearts. These women were up before dawn or even in the middle of the night to send their husbands off to work. Then they would often go off to work themselves. They did hard physical work, in the home and outside of it, that no modern person, male or female, would be able to do for more than a couple of hours.

These women weren’t “stay-at-home moms,” nor did they “have careers.” They worked to get by, in the canning factories, cleaning rich peoples’ houses, in the mess halls of the logging and fishing camps, in garment factories, and yes, those who were desperate, in the saloons and brothels. They worked cattle, tended gardens, harvested rye and alfalfa, planted potatoes, milked cows, knitted sweaters, made dresses, shirts, and trousers by kerosene lamplight. My grandmother would be baffled by the lack of skills we have today to do such things and amazed by how easy it is to buy such things. These women fed their families and raised their children, with no doctors, no medicine, and no money. This was hardship.

But there is a positive side to hardship. They had and immense dignity and a sense of pride about themselves as women, a special breed of human that was primarily responsible for sustaining the culture, making community, for “keeping things moving and making headway,” as Ina would often say. (She and her friends could also be petty, gossipy, and sometimes mean as snakes.) When I was small, I was allowed to hang out and listen to their earthy stories and jokes.

Deep River is infused with and imbued by the many stories I was privileged to hear, from my grandparents and their siblings and friends. The novel is not, however, about them. I made up its characters and their various love interests. They are not my relatives.

One particular story, of the many I grew up listening to, became a major part of the novel. One day I asked my grandmother, who I knew had been in the IWW, about a song that Joan Baez had popularized, The Ballad of Joe Hill. Hill was a famous IWW labor organizer.

“Did you know Joe Hill?”

There was a long pause. Then, out came, “That sonofabitch!”

“What?” We were talking about a ’60s icon here.

“That sonofabitch. We’d work one year, two years, working to get loggers and millworkers to hold the red card (i.e. join the IWW). He’d come to town. Sing some songs. Cops all over the place. People scared to death. Torn up red cards everywhere. Years of organizing down the drain.”

Now that’s a story that had to be written down.

I also wanted to share, perhaps even explain, a dark side to growing up in a community supported by what is still today the two most dangerous professions in the world, logging and fishing. While I was growing up, five of my friends lost their fathers to logging accidents. My Greek grandfather lost an eye in a sawmill accident and eventually ended up totally blind. My step-grandfather, Axel, had his legs crushed between two log booms. One was amputated. This was a major reason my brother and I worked for him. My biological grandfather, Leif, was crippled jumping from a runaway logging train. Unable after that to do anything but the most menial of labor, combined with the frustration of illiteracy for a man with a fine intellect, Leif succumbed to alcoholism. I remember several occasions driving with my mother to pick up Leif passed out on some tavern floor amidst the sawdust and vomit. Ashamed of his alcoholism, she didn’t tell us he was her father until we were teenagers.

The Kalevala is a work of Finnish poetry that became a focal point of the struggle for Finnish independence. It is Finland’s equivalent of Ireland’s Táin Bó Cúailnge, France’s La Chanson de Roland, and ancient Greece’s Iliad and Odyssey.I wanted to share the true cost of a 2 x 4 stud or a store-bought fish.

Still, I had a wonderful childhood. When I describe it to people, many think I must be repressing something. I assure you I’m not. Men dying when logging or fishing was just normal life, still is. I’ll even argue that growing up aware of how tenuous life is, makes one appreciate it more than someone who is sheltered from awareness of death. I had two loving parents who were real adults. I had freedom, unheard of today, to roam the woods and town. I had my own paper route when I was eight years old—and my own money. I also had an enormously rich ethnic and cultural heritage.

Five languages were regularly spoken in the house. My mother’s first language was Finnish, which she spoke with my grandmother who refused to speak English unless faced with no alternative. My father’s first language was Greek, which he spoke to his mother and father. Axel was Finnish-born, but Swedish-speaking. Leif spoke Norwegian to my mother, but Finnish to my grandmother. My brother and I survived this what we called linguistic and cultural schizophrenia by only speaking English. I can pass the butter and name the cookies in any of the five languages, but sustain a conversation in any of them, I cannot.

My initial concept of Deep River was to bring the characters and stories of The Kalevala to life in the America. The Kalevala is a work of Finnish poetry, compiled from oral folklore and songs in the mid-19th Century by Elias Lönnrot, that became a focal point of the struggle for Finnish independence from Russia. It is Finland’s equivalent of Ireland’s Táin Bó Cúailnge, France’s La Chanson de Roland, and ancient Greece’s Iliad and Odyssey. That idea didn’t work. There is no overarching narrative structure to The Kalevala. Still, the epic influences my stories.

I grew up interested in Norse and Finnish mythology, but that had nothing to do with my Scandinavian heritage. Neither my parents, grandparents, or great-uncles and aunts gave a damn about Norse mythology or The Kalevala. They worked—all the time. I came to love mythology, what my grandmother called “foolishness,” on my own. (I was first introduced to Irish mythology by our town librarian; she’d ordered Yeats’s Celtic Twilight for me from The Bookmobile, which came to town every other week from the state library in Salem. My interest in mythology was further enhanced by reading the works of Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell as a young man.) I reached my nerd pinnacle at Oxford when I was allowed into a seminar in Old Norse Poetic Diction, led by Ursula Dronke, who held the wonderful title of Vigfússon Reader in Old Icelandic Literature and Antiquities.

It was while taking that seminar (I was the only one who didn’t speak three dead languages) that I was introduced to the Icelandic sagas. I was drawn to Laxdaela Saga, a saga from around the 9th Century about the early Norse settlers to Iceland that involves a love triangle between Kjartan Olafsson, Bolli Thorleiksson, and Gudren Osvifrsdottir.

Throughout the novel, there are echoes of The Kalevala and Laxdaela Saga and their heroic characters. This was not a difficult leap. There was something truly heroic about men, no more than five foot eight or nine inches tall, sometimes taking several days to bring down an old-growth Douglas Fir or cedar with only axes and saws. These trees were over two hundred feet tall and often fifteen or sixteen feet in diameter. A single log weighed tons. They did this six-days a week, from dark to dark, in horrible living and working conditions, facing death and maiming every day.

I also wanted to write about the ironic result of that heroism, a few scattered parcels of old-growth forest outside of the national parks. 77 men died building the Grand Coulee Dam so we could have light at the flip of a switch. The Columbia River is now a series of lakes with 80% of the returning salmon raised in hatcheries and the runs are a fraction of their historic size.

I wanted to write about the ironic result of those male loggers’ heroism, a few scattered parcels of old-growth forest outside of the national parks. 77 men died building the Grand Coulee Dam so we could have light at the flip of a switch.Not only have we lost a pristine environment, we’ve also lost dances every week with friends and family, the music played on self-made instruments by friends you worked with during the day and would go to church with in the morning. Old country language and heritage has faded, kept barely alive by the occasional Scandinavian festival with women in traditional peasant dresses who don’t speak the old-country language. We’ve also lost enormous chunks of the culture and wisdom of the first peoples on this continent, those we call Native Americans, Indians, or First Nations.

Deep River is a historical novel, but it contains both warnings and advice concerning our present and future. During the time of the novel, Americans began to exchange privacy—and its protection against totalitarian government—for safety from perceived and increasingly manufactured enemies. The Espionage Act of 1917, an act still on the books that makes it illegal for someone to think about overthrowing the government, was sold politically on the promise of saving us from communists. It was used, under the banner of patriotism, to crush the Industrial Workers of the World, a union that was responsible for raising the wages of loggers to something that could support a family. Today’s Patriot Act and its daily assaults on our privacy (and dignity in airports) was sold politically to keep us safe from Muslim terrorists with little regard for its real and potential abuses of privacy and due process.

But Deep River is also about building community—and rebuilding it when it is shattered. It is about building community that includes people with wildly different ideas about how to organize that community, but who still can love each other and sit down and enjoy Thanksgiving dinner together. Many of the systems of societal organization clashing in the novel are still being debated today. What I hope comes across is not advocacy for one system or the other, but what Deep River’s principle characters learn over the course of the narrative.

Any system will fail if it is controlled by bad people. Good people, however, can make even a bad system work—and change it for the better. It’s ultimately not the system, but individual consciousness that makes the world a better place. Consciousness develops slowly—but surely. Reading good literature helps. It is my hope that Deep River will do its small part.

______________________________________

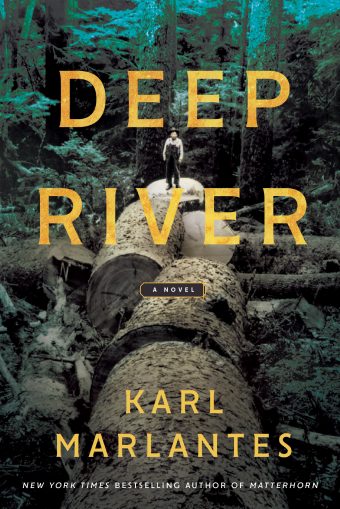

Karl Marlantes’s Deep River is out now from Grove Atlantic.