In Search of Visibility: Kao Kalia Yang on Sharing the Hmong Refugee Experience

“Each story that I share opens me up to and for the world in ways that I never knew were possible.”

For much of our life, my family and I have been largely invisible to the English-speaking world of mainstream America.

We were Hmong refugees living in the American Midwest. In St. Paul, Minnesota we lived in a small white house close to the corner of a sloped block, beneath the tall branches of an elm tree. Mom and Dad worked in the factories. My older sister and I took care of the younger children and went to school. We shopped at Cub Foods and the Asian stores with WIC vouchers and our parents’ hard-earned money. We washed our clothes at the corner laundromat—that still stands and serves the neighborhood, unchanging despite the years.

We took pride in the fact that we made it from one season to the next, our aged roof holding despite the heavy fall of snow and the wash of rain. In our little abode, cramped and moldy, we grew our collections of American movies via Columbia House and lined the floors with books we bought for pennies and dimes at the local libraries and the neighborhood garage sales. Our neighbors were diverse, some African Americans, a couple of Native and Latino families, but mostly comprised of new immigrants and refugees from the wars around the world. Many of them were Hmong like us, survivors of a genocidal attack after Southeast Asia gave way to Communism and the American interference in Laos. Our lives were not so different from the other impoverished people we lived with.

We understood as inheritors of their stories and their sorrow, that we were all doing the best we could.

My siblings and I were children fueled not only by the packages of instant Wai Wai noodles we ate for breakfast, sometimes lunch and dinner, but the dreams of our parents. Mom and Dad both were hopeful that if we go to school and do well and find honorable work, that our circumstances might shift for the better. While Mom did not speak so much of her expectations, afraid that we would crumble beneath the weight of their aspirations for us, our father fed us with his visions of our future.

In the future that we all hoped for, all my siblings and I would become educated, be healthy and wealthy, and more than anything else, be respectful and respected in the communities where we lived and grew our beautiful families. That future was a world draped in sunshine where the grass was green and the flowers abundant. That future was a place where we could run when life was especially hard—when Mom and Dad came home from work with sadness weighing them down, eyes dancing far from our gazes, because a supervisor at the factory had yelled at them without cause, a coworker had made comments about the food they brought in their shared cooler, a stranger in a gas station had spat in their direction, used a derogatory word they understood, then threw up an errant middle finger.

Their pain was our pain. In the future that we imagined, our mother and father, not just us, would be seen and understood for who they are: as individuals who have done what they can for themselves and their children under some of the harshest conditions and circumstances imaginable.

We were the children of refugees. Our mother and father had limited education. They grew into being beneath skies full of warplanes. Their run to freedom was a chase in the jungle where the bodies of family and friends fell like fallen fruit. In the refugee camps where they hoped for peace, they were stricken with the ghostly hands that tried to pull them back into the hungry mouth of death and despair.

In America, with no language to help, they found work using their arms and feet, the strength of their tired hearts to push and pull and plug away along the never-ending assembly lines. We understood as inheritors of their stories and their sorrow, that we were all doing the best we could, despite the judgement, the ignorance, the unknowing that surrounded us, that positioned us as debris—the refuse of war, the dredges of capitalism, the bloodsuckers of America’s bounty, her majesty, her dream for herself.

I live my life embodying the questions, holding them within the expanse of my skin.

Growing up, I knew no writers. Like the children of so many immigrants and refugees I went to school thinking that I could become a doctor (because my older sister had already said that she would like to become a lawyer). In the words of our father, “Lawyers protect our rights. Doctors heal what is broken in our bodies.” However, in my senior year of college, my grandmother, Youa Lee, a woman who had never been in a classroom, who could not read or write, died—afraid that she would be forgotten.

I wanted to become a writer to share all the things I would never forget about her. I didn’t know how to become a writer, so I shifted my education toward that cause. Instead of going to medical school, I went to writing school to pursue a Master of Fine Arts. I was twenty-seven years old when my first book, The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir was published.

Since, I’ve published two other memoirs, a co-edited collection, and five picture books. This year, I’ll publish another memoir, two more picture books, and make my middle grade fiction debut. I have written of our lives, the lives of other refugees, and shared the stories that speak to my heart for a world of readers who I may or may never meet. Each book that enters the world, each story that I share, opens me up to and for the world in ways that I never knew were possible, each pushes me to be more in touch with our shared humanity. These days, for the Hmong children in Minnesota and elsewhere, when they search for Hmong American writers, I am among the first they find.

What does it mean to be one of the first Hmong American writers published in America? What does it mean to be one of the most prolific and recognized? What does it mean that I am writing about our people? Sharing our stories? Sharing the stories that are adjacent to our lives? What does it mean that I am a woman? What does it mean that I am a Hmong woman married to a white man doing this work? What does it mean that I am raising children who barely speak my home language? The questions go on and on, each necessitates a different response, or many responses.

At 43 years old, I am a woman awash in questions, sailing on the wind of her words in search of possible destinations, places where I might be able to sit, set up a shelter, find food and water, savor the air, drink the water, and rest my heart for a bit before embarking once again to explore the seeds of who I am and who we are together and apart. In the words of my Uncle Shong, “The body works in the world, and tires in it.”

As the seasons shift, as I grow older, I feel waves of exhaustion come to the shore of my body, but also the strength of my beating heart. I don’t know that I have any answers, so I live my life embodying the questions, holding them within the expanse of my skin, the reach of my bones, the strength of my muscles, the expanse of my imagination, the parameters of my being—all in search of visibility.

__________________________________

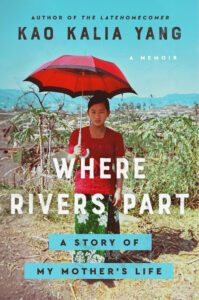

Where Rivers Part: A Story of My Mother’s Life by Kao Kalia Yang is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Kao Kalia Yang

Kao Kalia Yang was born in a refugee camp in Thailand and came to America at the age of six. She is the author of The Latehomecomer, The Song Poet, Yang Warriors, and most recently, Where Rivers Part. She also coedited What God Is Honored Here? and is the author of a collective memoir about refugee lives called Somewhere in the Unknown World.