In Search of Shirley Jackson’s House

Walking in Jackson's footsteps in Bennington, Vermont

Four years ago, in July 2012, I drove from my home in Pennsylvania to the small village of North Bennington, Vermont, to research author Shirley Jackson, who was born 100 years ago this December. Jackson lived and wrote in North Bennington for 17 years—over half her adult life. She also died there, suddenly, upstairs in her own house, on August 8th, 1965. The cause was heart failure. She was 48.

I had been to North Bennington once before, in July 1979, to attend a writing workshop at Bennington College. At that time, I had no idea Jackson had lived just a few feet from the college’s back entrance. I also had no that Jackson’s husband, literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, had taught at the college for 25 years. I had no inkling of the 1946 disappearance of Bennington College student Paula Jean Welden who had gone for a hike alone on a nearby wooded trail and to this day has never been found. The mystery inspired Jackson to write her second novel Hangsaman (1951). (Welden’s story would also inspire Donna Tartt, who was a student at Bennington in the 1980s, to write her 1992 novel, The Secret History.) Finally, I had no idea that in addition to her gothic fiction, Jackson had penned rollickingly funny magazine essays about raising her four children that were collected and published in Life Among the Savages (1953) and Raising Demons (1957). Single and in my twenties in 1979, the fact that Shirley Jackson was a mom would not have interested me. Years later, after I became a mom myself, the lives of writers who are mothers became a point of fascination for me.

What an opportunity I had missed by not knowing all this in 1979.

Here I must confess: I am a geek about writers’ houses. I will go out of my way to see the home of a writer who interests me. On the one-month anniversary of 9/11 I braved terrorism warnings in order to travel from Philadelphia to the edge of New York City, up the Palisades Parkway and across the Tappan Zee Bridge to interview William Styron at his house in Roxbury, Connecticut (where I discovered he kept his Pulitzer Prize in the guest bathroom). On another occasion, when I found myself within a few hours drive of the Harriet Beecher Stowe house in Hartford, Connecticut, I ignored post-hurricane flood warnings to go there. (Bonus: Mark Twain was a neighbor of Stowe’s and I could see his house also.)

How to explain such an addiction, which I have had almost all my life? Being a fan of certain writers means I am familiar with and extremely interested in their work and their biography. So I learn even more by seeing the spaces they inhabited—even if I cannot go inside the residences. Simply by standing in the same places these writers once stood, seeing what they saw out their windows and on the streets, seeing what surrounded them and may have influenced their writing—I obtain an even deeper understanding of their work. Very often—and especially in Shirley Jackson’s case, the mood of where they live, along with actual physical landmarks are incorporated into the author’s work. I find it both fun and enlightening to get this very clear sense of place about an author.

Moreover, writers are my celebrities. To be in their presence, whether in person—I also love to go to book signings and readings—or in a space where they may have lived, is thrilling to me. I even like to visit writer’s graves. Perhaps I think being in the proximity of a writer I admire will cause his or her writerly sensibilities to rub off on me. Because mostly my author addiction is about my lifelong quest to be a writer myself and understand all I can about writing.

All this is to say that, since my clueless first visit to North Bennington, as I became more steeped in knowledge of Shirley Jackson through my reading and research of her—I found myself regretting what I had not seen in 1979. I decided to remedy the situation. And that’s how in 2012 I wound up planning to go to North Bennington for a second time, to follow in the footsteps of Shirley Jackson.

Before leaving for North Bennington this second time I was determined to do my homework. First I checked online to see if I could find an exact address for where Jackson had lived. I initially went to the website writershouses.com, where I stumbled upon an essay by Susan Scarf Merrell (author of Shirley: A Novel) called “Shirley Jackson Doesn’t Have a House.” The title made my heart stop. But I soon discovered that what Merrell meant was: Shirley Jackson doesn’t have a house open to the public, or even one that has a plaque on it commemorating her time there. So I needed an address.

I was next led to a blog called “Unabridged Chick” run by book reviewer Audra Friend, who had undertaken a similar trip to mine in 2011 (apparently I am not the only writer’s house geek). I emailed her, and she provided me with the house number I needed.

My main source of background information this time was Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson by Judy Oppenheimer (1988). Since 2012, a wealth of new material and research related to Shirley Jackson has been found. Much of this new information has been published in Let Me Tell You: New Stories, Essays, and Other Writings, edited by two of Jackson’s children (2015); and in the just-published Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin. These books inform my thoughts as I look back on my 2012 trip.

* * * *

It’s about a 300-mile/six-hour drive from my house outside Philadelphia to where Shirley Jackson lived. I got off to a late start, so it was dark as I crossed from New York into southern Vermont and entered downtown Bennington. The town was alive with festive lights and summer tourists on the sidewalks lining wide streets and plentiful shops and restaurants.

Many people mistakenly believe Shirley Jackson lived in this seasonally bustling, somewhat upscale part of Bennington. In fact, Jackson spent her years in the smaller and sleepier incorporated village of North Bennington, a former mill and factory town about five miles northwest of Bennington’s downtown. For many of her years there, she and her husband did not own a car or drive. Later, it would be Jackson who would chauffeur her husband and family around. But most of the years Jackson spent in North Bennington were isolated. You can feel that atmosphere of isolation in her fiction.

The scenic route to North Bennington winds past strip malls and big-box chain stores on a road that was likely tree-lined in Jackson’s time. The poet Robert Frost is buried in a cemetery about a mile away from this road as the crow flies. There is no grave for Shirley Jackson here or anywhere else, however. According to the website findagrave.com, Jackson was cremated and the ashes are in possession of her youngest son, Barry Hyman, who was 13 when his mother died.

The route I was traveling took me by the hidden wooded campus of Bennington College, and then swung to the right onto Main Street and into the quiet, less-than-one-square mile village of North Bennington. Before entering the town square, I turned right onto Prospect Street, drove about halfway up, and came to the house where Shirley Jackson lived when she first moved here in 1945 when she was 29.

Shirley Jackson’s house, the Greek Revival on Prospect Street in North Bennington (photo by the author)

Shirley Jackson’s house, the Greek Revival on Prospect Street in North Bennington (photo by the author)

The house on Prospect Street is striking in its architecture: an 1850 Greek Revival mansion complete with four two-story columns. “Like a minor Greek temple” Jackson once described it. The columns make the house easy to find even without an address. For confirmation I had but to look at the cover of my 1993 copy of Life Among the Savages (a book which Jackson’s children liked to call Life Among the Cabbages) on which a drawing of the house appeared, albeit with a circular window on the second floor as opposed to the fanlight on the real-life house.

How exciting to see this house in person, as if it had sprung alive from a fairy tale illustration! How fabulous to stare at the windows and imagine Shirley Jackson inside. All the madcap adventures she chronicled in Life Among the Savages happened in this house, and I could see them now clearly in my mind’s eye. I could further imagine Jackson in there doing dishes while making up stories, as she had written in an essay. I saw her changing sheets and emptying ashtrays (ubiquitous jobs: both she and Hyman smoked, as did many of their frequent famous writer guests). And I could see her at her typewriter, always writing amongst the chaos, as much as she could, sitting downstairs in floor-to-ceiling book-lined rooms. When Jackson was not able to sit at her typewriter, she was writing in her head.

“I cannot find any patience for those people who believe that you start writing when you sit down at your desk and pick up your pen and finish writing when you put your pen down again; a writer is always writing, seeing everything through a thin mist of words, fitting swift little descriptions to everything he sees, always noticing,” wrote Jackson in a craft essay.

“We recall coming home from school and finding our mother typing away downstairs or at a folding table in the dining room, or sitting on her kitchen stool making notes while making brownies,” remembers eldest son Laurence Jackson Hyman in the afterword to Let Me Tell You. “For years, our parents worked side by side in their study, sitting at desks four feet apart, the sounds of their furiously fast typing rattling through the house.”

The years the Hymans spent at the rented house were indeed productive ones for Jackson. She wrote and published her first novel, The Road Through the Wall, while living here, as well as seven short stories, including “Charles” (the story of a kindergartner who came home every day to regale his family about the disruptive antics of a naughty child who, the mother eventually finds out, is actually her son, the storyteller); and “The Lottery.” Jackson had her second and third child while living here as well (her first child had been born in New York City).

One of the first works Jackson wrote in this house was “Flower Garden,” a short story about racism, the ugliness of which she would witness in North Bennington, and the practice of which she had been keenly aware since growing up in California, where she knew about the internment of Japanese Americans. As Mrs. Stanley Hyman, Jackson also had a front-row seat to the anti-Semitism that was particularly virulent in her lifetime. Jackson’s observations of prejudice, hypocrisy and human cruelty lurking just beneath the surface of things along with her own dark experiences of being treated as an outsider would directly contribute to her writing of “The Lottery” as well as other stories.

It was also in this house that Jackson would read the initial three hundred or so letters from readers that inundated the tiny North Bennington post office in response to the story’s June 26th, 1948, publication in the New Yorker. People were shocked and upset by the story. The New Yorker had never before (nor since) received such a voluminous response to something it had printed. Many of those letters were as hate-filled as posts from today’s internet trolls. Jackson would continue to receive letters about “The Lottery” her entire life.

There is a well-known story about how Jackson came to write “The Lottery”—a story Ruth Franklin has partially debunked in her new biography. The story goes that Jackson, pregnant with her third child, was pushing a stroller containing her second child, a daughter. They were coming back from their daily walk to the post office when the idea for “The Lottery” hit Jackson full-blown. As Jackson tells it, she came home, put her daughter in the playpen, wrote the story in one draft with no changes, submitted it, and it was published almost immediately. Franklin has established that there actually were some edits, and that publication was not as speedy as Jackson said.

These are minor details, Franklin says, but important in that they demonstrate Jackson’s tendency toward “mythmaking.” For example: Jackson was largely responsible for the myth that she was a practicing witch. She wrote this “fact” somewhat offhandedly in the bio for her first novel. When people believed it—it was true she was interested in magic, read Tarot cards and such, and had a whole library on the occult and magic—she did nothing to disabuse them of the idea. She actually took it further and exhibited more “evidence” that it was true: Jackson always had six or more cats that would be all the same color—usually black, sometimes gray—and she happily allowed people to believe the cats were her familiars. The truth was more humorous: her cats looked all the same so that her husband, who was not fond of cats, and could not see well enough to tell the cats apart, would not realize how many cats she actually had.

Humor aside, Jackson’s marriage with Hyman was problematic from the beginning. The two met as undergraduates at Syracuse University, after he’d read a short story by her in the university literary magazine. He fell in love with her through her writing, having not yet even met her.

“Who is Shirley Jackson? I am going to find her and marry her!” Hyman told one of his fraternity brothers.

And he did. The marriage, which took place in 1940 soon after they graduated, brought wrath upon both their heads from both families. Jackson’s parents were shocked and horrified because Hyman was Jewish. Hyman’s father disinherited and disowned him because Jackson was not Jewish. It was only later, after the children were born, that Hyman’s father reconciled with him.

Stanley Hyman, for his part, was always and forever Jackson’s greatest admirer, at least for her genius as a writer. But their marriage would not be a rosy one. Stanley would cheat on her with fellow students at Syracuse and his own students when he later became a Bennington College professor, causing Jackson excruciating emotional pain and turmoil. For all of Hyman’s support and praise of Jackson as a writer, he did nothing to support her actually getting her writing done. Like the stereotypical 1950s husband, he left everything domestic involving the house and the children to her.

A story told by a neighbor in Private Demons gives “a clear glimpse into the inner workings” of the Hyman marriage:

[The neighbor]… was out on his front porch one morning and saw Shirley, hugely pregnant, struggling up Prospect Street carrying mail, newspapers, and two bags of groceries. He was about to go down and offer her a hand when Stanley burst out of the house and ran down the street to meet her. But to [the neighbor’s] horror, instead of relieving her, Stanley carefully removed the mail from her hand and trotted back up the street. Shirley, still clutching her bags, continued to trudge up the hill to her house.

Powers Market (photo by the author)

Powers Market (photo by the author)

Many have called North Bennington a place that time forgot, and in many ways, it does seem like a town from the past. Powers Market, where Jackson did most of her shopping, and still extant, is located in a former company store building built in 1835. Main Street also includes a public library, a post office, the historic North Bennington Depot railroad station, and a former bank, now an art and community center where an annual Shirley Jackson Day has just recently started being held in June. When Jackson lived in North Bennington there was also a place called Percey’s Newsroom where she would buy the daily newspaper.

The North Bennington train station on Main Street, not far from Shirley Jackson’s second house. (photo by the author)

The North Bennington train station on Main Street, not far from Shirley Jackson’s second house. (photo by the author)

At the foot of Prospect Street was The Rainbarrel, a French Restaurant that in 2012 was an American restaurant called Pangaea. It was in The Rainbarrel that, three months short of the fifth anniversary of Shirley Jackson’s death, Stanley Hyman, in the company of his pregnant second wife and former student, would suffer a heart attack and die.

There are actually two Shirley Jackson houses in North Bennington: The Prospect Street one which she and her husband rented for 50 dollars a month and lived in from 1945 to 1948—a period when the Hymans were financially strapped; and the one on Main Street less than a mile away. Jackson bought the Main Street house 1953 with the $15,000 earnings she’d received from Life Among the Savages. By that time she had become the main breadwinner of the family—largely due to her magazine writing, which fetched around $1,000 per essay.

Both Shirley Jackson houses are large and rambling—14 rooms in the first one, 20 in the second. Each has a porch in front and an outbuilding in the back. Jackson described the Prospect Street house as having five attics! Jamaica Kincaid, who has spent summers in North Bennington, set her 2013 novel See Now Then in the Prospect Street house. Prospect Street ends at the blocked back entrance to the Bennington College campus. Before Jackson started driving him to work, Hyman would have walked along a small road through a high-grassed field to get to his classes on campus.

After a brief move to Westport, Connecticut, in 1949, the Hyman family—now with four children—returned to North Bennington, living first in what was called “The Orchard” on Bennington campus, and then later in the nearby house of famous psychologist Erich Fromm while he was away in Mexico. In 1953, they ensconced themselves in the North Bennington Main Street.

The second Shirley Jackson house, on Main Street in North Bennington, VT (where Shirley Jackson died). (Photo by the author)

The second Shirley Jackson house, on Main Street in North Bennington, VT (where Shirley Jackson died). (Photo by the author)

On the July day in 2012 when I went looking for the Main Street house—this time I had no house number, just a description—the screen door was closed but the main front door behind it was open. Something told me I could knock on that door and inquire about Shirley Jackson. Sure enough the owners of the house (the husband has since died; the wife has moved away—I was asked not to use their names) were home and invited me in.

It was at first a little eerie and somehow sacred to be standing in the house where Shirley Jackson had taken her last breath.

Jackson had, in those later years in the Main Street house, not been in the best of health. She had previously been prescribed barbiturates for weight loss and codeine for debilitating headaches. These had taken their toll. She had high cholesterol and high blood pressure. She suffered from anxiety and depression—old nemeses—as well as, in the final years, colitis and agoraphobia.

It had been a hot summer, and Jackson had acquired the habit of taking an afternoon nap. That day, a Sunday, Jackson went upstairs for her nap as usual and was never seen alive again. Jackson’s third child and second daughter, Sarah, who had been asked to waken her mom at 4pm, was the one to discover that her mother had died in her sleep.

My kind hosts had first rented this house fully furnished from Hyman while he taught in Buffalo. In 1968 they purchased the house from him. When they first moved all the walls on the first floor were covered with bookshelves “as high as they could reach and even across the archways” of the door, they said—and even covered all of the windows.

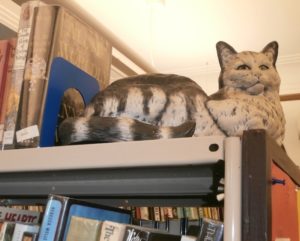

One of the ceramic cats from Shirley Jackson’s collection, on display at the John G. McCullough Free Library, North Bennington, VT (photo by the author)

One of the ceramic cats from Shirley Jackson’s collection, on display at the John G. McCullough Free Library, North Bennington, VT (photo by the author)

Bookshelves blocked one of two doorways to Hyman’s study. As a teenager, the Hymans oldest son built bookcases for his parents on the upper floors of the house, including the attic. According to my hosts there were some 40,000 books in the house when they moved in. This is easy to believe. It is well documented that when the Hymans moved briefly to the Westport, Connecticut house their books alone weighed ten thousand pounds and filled one full-size moving van. Some of the Hyman/Jackson books wound up in the village’s public library, along with a number of ceramic cats Shirley Jackson collected.

How many stories had Jackson composed in this house, perhaps in this very kitchen? Raising Demons was written here, as was The Sundial, The Bird’s Nest, The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle finally put Jackson on the New York Time’s best-seller list. At the time Jackson’s mother, who throughout Jackson’s life wrote her letters laced with criticism, continued the tradition by writing a letter that ignored Jackson’s literary achievement. Instead, as she so often did, she attacked Jackson’s appearance:

“Why or why do you allow the magazines to print such awful pictures of you?” she asked her daughter. “I have been sad all morning at what you have allowed yourself to look like… You were and I guess still are a very willful child who insisted on her own way in everything.”

Shirley Jackson spent a lifetime wanting—and never getting—her mother’s approval. The basic clash came from the fact that Jackson’s mom had wanted a debutante-like “good girl” for a daughter. Instead she got a “rebellious” artist. Jackson never confronted her mother about the deep hurt and rage her criticism caused her. But as is often the case with a writer, her true perspective came through in her work.

In The Haunting of Hill House, for instance, there is the famous scene where the protagonist, Eleanor, observes a little girl refusing to drink her milk:

“… the little girl was sliding back in her chair, sullenly refusing her milk, while her father frowned and her brother giggled and her mother said calmly, “She wants her cup of stars.”

Indeed yes, Eleanor thought; indeed, so do I; a cup of stars, of course.

“Her little cup,” the mother was explaining, smiling apologetically at the waitress… “It has stars in the bottom, and she always drinks her milk from it at home. She calls it her cup of stars because she can see the stars while she drinks her milk.” The waitress nodded, unconvinced, and the mother told the little girl, “You’ll have your milk from your cup of stars tonight when we get home. But just for now, just to be a very good little girl, will you take a little milk from this glass?”

Don’t do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head stubbornly at the glass. Brave girl, Eleanor thought; wise, brave girl.

My hosts served me tea and just-baked cookies in what was once Shirley Jackson’s kitchen. On a counter by the door sat one of authors remaining ceramic cats. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life contains a detail about this house that I had never before read. When Jackson first moved in, Franklin writes, “she pasted silver stars of all shapes and sizes” on the kitchen ceiling,

I wish I had known that on that day I sat having tea in Shirley Jackson’s kitchen. I wish I had known to look up. I remembered I had the email of the former owner of the Main Street house. I quickly wrote and asked if she had ever seen those stars on the ceiling. She hadn’t. But I like to think of the time when they were there.

I like to think of how they might have, by reflection, made a cup of stars for Shirley Jackson as she sat—perhaps exactly where I had sat—drinking her cup of tea.