In Pursuit of the Elusive Spanish Forger

Lydia Pyne on One of the Great Art Criminals of All Time

On Wednesday, May 23, 2012, the British auction house Bonhams began accepting bids for items from one of the most impressive collections of forgeries amassed during the 20th century. There were phony letters attributed to the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and the novelist George Eliot. A few faux medieval panels and paintings. Some fake Shakespearean ephemera. Ardent enthusiasts of all famous historical things fake, welcome to the sale of the celebrated Stuart B. Schimmel Forgery Collection!

During his life, Stuart B. Schimmel was a respected collector of rare books, manuscripts, engravings, and historical printing technologies, following his successful career in business and accounting. “He brought verve and élan to the grand collection he amassed,” John Neal Hoover lauded in his 2013 memorial, noting that Schimmel was “a true adventurer in the pursuit of books and the ways they can order one’s life.” in addition to building a traditional art portfolio with works by recognized masters, Schimmel spent half a century collecting superb forgeries, frauds and fakes.

Schimmel got his start collecting forgeries when he offered to buy a Lord Byron signature from his friend, Colonel Drake, who had unwittingly purchased a very good Byron forgery. (Schimmel graciously agreed to sell the signature back to Colonel Drake if, at some point in the future, it proved genuine.) From there, Schimmel went on to collect only the very best fakes, with items boasting amazing provenances and stories, rarities that commanded impressive prices. (“Provenience” to refer to the position of an artifact’s discovery, like at an archaeological site. “Provenance” refers to the cultural and custodial history of an artifact or object once it has entered a museum or collector’s context.) He collected the ersatz with enthusiasm as well as a discerning eye. All of the fakes in his collection, you see, had been authenticated.

These forgeries prove that fakes can be more than just the stories of them being debunked.

“The motivation for forgery is always complex, whether done for gain or fame, to prove a point or in the belief that something should exist even if neglected by its purported author,” renowned book collector Nicolas Barker suggested in the introduction to the 2012 Bonham’s catalogue that listed the Schimmel lots. “There is no such difficulty with Stuart’s collection. All his are genuine forgeries. He has had a lot of pleasure out of collecting them, and the books about them. It is now the turn of others to enjoy the same pleasure in their dispersal.”

Among the many impressive authentic forgeries Bonhams listed in its sale, the masterpieces of two fakers stand out as intriguing genuine fakes—the works of the Spanish Forger and William Henry Ireland. The Spanish Forger painted and sold faux medieval images during the late 19th century and William Henry Ireland is famous for his 18th-century fraudulent William Shakespeare signatures and invented plays. The celebratas of these forgers and their forgeries explains why they were in the Schimmel collection to begin with, as both have become fashionably and lucratively collectable in their own right. These forgeries prove that fakes can be more than just the stories of them being debunked.

*

“The Spanish Forger was one of the most skillful, and successful, and prolific forgers of all time,” William Voelkle, Curator of Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at the Morgan Library, contends in his numerous publications about the Spanish Forger’s work throughout the late 20th century. Full of admiration for the Forger’s talent and audacity, Voelkle argues that “until recently his numerous panels, manuscripts, and single leaves were appreciated and admired as genuine 15th- and 16th-century works.” Now they are increasingly sold, collected, and even exhibited as his forgeries.

The story of the Spanish Forger begins in Paris. In the latter half of the 20th century, Paris was not only the center of influential arts movements, but also a headquarter for forgery production targeting tourist markets in the city as well as agents buying on behalf of high-end collectors and museums. The presence of less than genuine art was ubiquitous, whether that took the form of a copy, a replica or an outright forgery.

The issue of forgeries became so prevalent that in 1904, the French art historian and critic Count Paul Durrieu published a series of scathing articles warning his readers that the markets were rife with fakes. Whatever sort of art people wanted to buy, Durrieu argued, that art was being faked (and some of it was even being faked well). Although Durrieu did not mention any specific works that would later be attributed to the Spanish Forger, it is clear from the pieces that he did highlight that the Spanish Forger would have known how to work the Paris market of fake art. The Spanish Forger recognized just what sorts of fakes would be snapped up by enthusiastic, if somewhat gullible, buyers.

For decades, the Spanish Forger’s work slid under the art world’s radar, working their way into a plethora of collections, both private and institutional. The odd, newly discovered work still shows up, even today; as recently as 2016, a “new” Spanish Forger piece was discovered and authenticated by the Antiques Roadshow. Although rumblings of fakery surrounded a couple of the Forger’s manuscript pages early on in his story—in the mid-1910s—it wasn’t until 16 years later that the faker and his phony medieval art were formally recognized in the communities of art authentication.

In 1930, Ms. Belle da Costa Greene, director of the Morgan Library, was asked to authenticate The Betrothal of Saint Ursula, a purported Jorge inglés 15th century painted panel. Maestro Jorge Inglés was a well-known painter and illuminator in the mid-15th century, primarily painting out of Castille; one of inglés’s best known panels is the Altarpiece of the Gozos de Santa María (known colloquially as the “altarpiece of the angels”), a panel considered by many scholars to show the intersecting Hispano-Flemish painting traditions. Acquiring an Inglés would have been a coup for any museum, which is why the purchasing agent for the Metropolitan Museum of art’s board of trustees, Count Umberto Gnoli, was eager to add The Betrothal to the Met’s collection. The Betrothal of Saint Ursula had already been authenticated by Sir Lionel Henry Cust, whose opinion Gnoli accepted. In order to shore up the board’s confidence in the panel’s authenticity, Gnoli hoped that Greene would endorse the panel and recommend that the board acquire it. The asking price was £30,000.

Bella da Costa Greene is an enigmatic character in the Spanish Forger story. Twenty-five years before coming across The Betrothal of Saint Ursula, she was hired by John Pierpont Morgan as a librarian to manage his then ever-growing collection of art, antiquities, manuscripts and rare books. Junius spencer Morgan II—Assistant Librarian of rare books at Princeton university and John Pierpont’s nephew—introduced Greene to his uncle and arranged for her initial job interview.

Belle da Costa Greene was born Belle Marion Greener, the daughter of Genevieve Ida Fleet and Richard Theodore Greener, who was (in 1870) the first black graduate of Harvard university. Greene grew up in Washington, DC, in what historian Heidi Ardizzone describes as a struggling elite community of people of color—well educated, well connected, but still very much situated in the racism of early 20th-century America. Around 1900, after her father had separated from her mother and taken a post as a US diplomat in Siberia (where he subsequently had a second family), census records show that Belle’s family began to vary their names. Before she arrived at Princeton, Belle dropped her middle name, “Marion”, and added da Costa.

When Greene began work at “Mr. Morgan’s Library” in 1905, she brought with her the expertise in illuminated manuscripts that she had acquired at Princeton. She started as Morgan’s personal librarian at a salary of $75 a month, and over the next four decades would handle millions of dollars of business for J. Pierpont Morgan and, after his death in 1913, for his son Jack. She eventually became the Director of the Library when it was made a public institution in 1924, and steered the collection and the library to be one of the foremost of the 20th century.

Perhaps most significant to Belle’s own biography, however, is her decision to create her own origin myth—her own story of where she came from—and use it to leverage her considerable intellect to her advantage. In her initial interview with Morgan, she said that her mother was of southern nobility, fallen on hard times, and that her grandmother was of Portuguese descent, explaining the da Costa part of her name as well as what newspapers of the time called her “exotic” appearance. According to Ardizzone, just how Belle’s biracial heritage impacted her identity is an open question—Belle famously burned her personal correspondence before her death and carefully controlled her public persona over her 43-year career.

Belle da Costa Greene looked at the painting’s Medieval halcyonic utopia and concluded that there was something hinky about the whole thing.

Although Belle was openly extolled as a leading scholar of illuminated manuscripts, she never worked in academia or held a formal university profession, and never published scholarly research or books. She did, however, as one her admirers noted, “transform a rich man’s casually built collection into one which ranks with the greatest in the world.” Greene easily held her own among the intelligentsia and aristocracy in new York City and Europe, and in 1939 she was the second woman elected as a Fellow to the Medieval Academy of America. Greene embraced her reputation as a bohemian librarian, known for her acerbic wit. In one of her most-quoted quips, she resoundingly rejects the dowdy stereotyping of her profession. “Just because I am a librarian,” Belle declared, “doesn’t mean I have to dress like one.”

*

When Count Gnoli sent a picture of The Betrothal of Saint Ursula to Belle da Costa Greene in 1930, he had no idea that the panel would kick off of a decades-long hunt for one of the most elusive forgers in art history.

The Betrothal of Saint Ursula is a downright idyllic painting. It’s also considerably hefty. After spending months looking at prints and scans of The Betrothal in art books or posted online, I had internalized the painting to simply be page-sized, despite dutifully typing out its dimensions multiple times. When I put in a request to see The Betrothal at the Morgan Library, the librarians wheeled it out on a dolly, carefully propped up on foam blocks. The size of the panel caught me by surprise. It measures 60cm (24in) across and just about 76cm (30in) tall, not counting the massive frame and box the piece is stored in. The librarians told me that they were excited to see it in person, as it’s a rarely requested item from the Morgan collection.

In The Betrothal of Saint Ursula, lollipop-like trees dot the background and small ships bob around in a harbor. A Lancelot-and-Guinevere styled couple wend their way from one castle to another. All of the figures have little bow mouths, pursed into syrupy smiles. Ursula demurely offers her hand to her green-sleeved fiancé, and her noble ladies-in-waiting mince down the lane in their bejeweled headdresses and low-cut dresses. White, puffy clouds fill the blue skies and you can’t help but get the sense that it’s always sunny in Saint Ursula’s world. Belle da Costa Greene looked at the painting’s Medieval halcyonic utopia and concluded that there was something decidedly hinky about the whole thing.

There was something—or some things—that simply didn’t sit well with her. It was cracked—with age? Maybe? Maybe not?—but the cracks conveniently stopped before they destroyed any of the figures in the painting. It was just too . . . something. Too cutesy. Too perfect. Too many unflawed details that didn’t quite add up. Ironically, the panel just looked too Medieval.

After a thorough analysis, Greene concluded that The Betrothal of Saint Ursula wasn’t a Jorge Inglés and that it certainly didn’t date to any semblance of the Middle Ages. She jotted down her conclusions on the back of a color illustration of The Betrothal that had been reproduced in Art News (1929), where Sir Lionel Henry Cust had originally attributed it to Inglés.“ Brought to me by Count Gnoli, who was then purchasing agent in Italy, for the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Belle da Costa Greene recorded, “who asked me to “back him up” in its importance for the Museum when it was to be passed on by the Trustees.” She christened The Betrothal’s artist the “Spanish Forger”—because The Betrothal was purported to have been the work of a Spanish artist—put the panel as having been painted at the turn of the 20th century, and over the next nine years, began to create an oeuvre that carefully documented this faker’s faux medieval works. Incidentally, but unsurprisingly, the Metropolitan Museum of Art declined to purchase the painting.

Although Greene began the systematic work of documenting known instances of the Spanish Forger’s work, two of his specific pieces had already raised questions as early as 1914. Salomon Reinach, the famous French archaeologist and antiquities expert, exposed one painting, The Portrait of a Young Lady of Sixteen, as a forgery; later that same year, Reinach and Henri Omont found another fake medieval work in a copy of an illustrated Juvenal manuscript. In both cases, however, the work was simply categorized as “fraudulent” and remained unattributed to a specific artist. That changed with Belle da Costa Greene’s frank assessment of The Betrothal of Saint Ursula. Now, The Portrait of a Young Lady of Sixteen as well as the Juvenal were attributed to the Spanish Forger.

It turned out that Greene had seen the Forger’s work before. The Morgan Library itself had one of the Spanish Forger’s works that Greene had authenticated in 1909—a medieval liturgy book—and the Forger had even finagled his way into the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of art. Greene’s list—which eventually totaled 14 items during her curatorial tenure—has continued to grow in the ensuing decades, as art experts ferreted out more examples of the Forger’s work among public and private collections.

“As I have been interested in my artist friend, whom for want of a genuine name I call “the Spanish Forger,” I am delighted to learn from your letter of September 26 that you have uncovered several others,” Belle da Costa Greene wrote to Charles Cunningham, curator of paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Cunningham in 1939, the like most of the curatorial art world, had learned that Greene was on the hunt for the Forger and was happy to help. “I think that he (or the factory) started in the manuscript field, although I have seen several paintings undoubtedly by the same hand . . . I have no doubt that I shall be able to run them all down to manuscript originals. The last one I discovered was really fantastic.”

Curators sent Greene photographs of potential Spanish Forgers, both those in their own collections and ones that were up for auction. “Thank you for the photographs which arrived this morning,” Greene wrote to Cunningham in a subsequent letter, in late September 1939. “Yes—they are all examples of my dear old pal.” Two years later, however, the charm of this errant scamp’s forgeries was wearing a bit thin. “I am infinately [sic] ashamed not to have thanked you before this for your letter of September 17th and the accompanying photographs,” Belle da Costa Greene groused to Charles Cunningham. “The “guy” is becoming rather tiresome, do you not think? Two of these photographs are practically duplicates of two others I have.’

For decades, many have tried to put a name, or at least a definitive nationality, to the Forger. Scholars can trace the Spanish Forger’s inspiration to a five-volume series published by Paul Lacroix in France in 1869-1882, which offered detailed illustrations of Medieval and Renaissance life; they have even pinpointed which specific Lacroix motifs the Forger used in his various pieces. Using the publication dates of this series to culturally triangulate when the Spanish Forger was actively painting, scholars surmise that his earliest work was in the early 1900s, and decades later scholars would trace the provenances of various Spanish Forger pieces to Paris.

Today, the true identity of the artist remains unsolved—we don’t know his nationality, his life story or even if the artist was a man. And that mystery is undoubtedly a key part of the Spanish Forger’s continued fascination and appeal.

——————————————

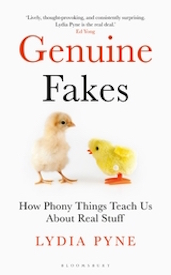

From Genuine Fakes by Lydia Pyne. Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Sigma, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © by Lydia Pyne, 2019.

Lydia Pyne

Lydia Pyne is a writer and historian, interested in the history of science and material culture. She has degrees in history and anthropology and a PhD in history and philosophy of science from Arizona State University, and is currently a visiting researcher at the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Her field and archival work has ranged from South Africa, Ethiopia, Uzbekistan, and Iran, as well as the American Southwest. Lydia's writing has appeared in The Atlantic, History Today, Time, The Scientist, Nautilus, The Appendix, Lady Science and Electric Literature as well as The Public Domain Review, and her previous book was Seven Skeletons, the story of human origins. She lives in Austin, Texas, where she is an avid rock climber and mountain biker.