In Praise of the Liminal Spaces and Uncertain Endings of Folklore

Thao Thai on the Forward Momentum and Emotional Resonance of Handed Down Stories

When I began writing my novel, Banyan Moon, I arrived on the page with an image of a locked trunk. I could picture it in startling detail: scuffed steel with dented sides and an embossed honeycomb grid, bearing the tacky aftermath of stickers ripped too quickly, trailing white hairs caught in the grooves of the decorative nails. The trunk of my imagination was locked, of course. What is a story but a locked trunk, holding the secrets of character and plot, the promise of all that is ugly and true?

If I go further back in time, I remember other trunks. There was a story my mother told me late at night, when I was a child and we shared a trundle bed in a stuffy room in Florida. She described cavernous hallways through which cold breezes blew, carrying a whiff of something saline and earthy. A scent to lead into a nightmare.

In the story, her hand twisted on a forbidden doorknob, revealing a trunk that only she could open with the pilfered key drawn from under her shirt. Inside, the trunk held the messy detritus of violence, a thousand stories cut short. I was horrified, and I wanted more. I’d ask the question dancing on the tongue of every story-gobbler: “What happens next?” She shrugged, not meeting my eye. Possibly thinking of those screams that never found release.

Now, I know she was telling me a version of the Bluebeard story, but back then, I thought she was talking about her own troubled marriage with my father. For years, I held this image as truth, not folklore. I suppose it was a mix of both, as many stories are.

*

I come from a family of adept tale-spinners. The musicality of their cadence combined with their muscularity of language demanded a listener’s attention. They performed with their whole bodies—hands thrust to the heavens, necks tense with anticipation. Sometimes, they’d tell true stories of their lives, but more often, still pained by their pasts, they’d reopen the cache of old folktales. With the overhead fan blowing mighty gusts, night dimming the room to purple, we lay on an old bedsheet, listening until even the crickets stopped sounding.

I heard stories of wise rabbits and regenerating serpents; giant turtles gulping swords; children who fed their starving parents strips of their own flesh. Unlike fables, folklore doesn’t always have a discernible moral, a near conclusion. The happy ending can be elusive; in some ways, suffering is the point. Hope, too.

Later, when I took folklore seminars in graduate school, I was fascinated by the range and variation across the world. So many cautionary tales. So many terrible stepmothers. Blood soaking each word, danger around each bend. I appreciate folklore for the way it cuts to the heart of it all: life, death, vengeance, passion. Now, when I overhear my own daughter playing a pretend game, I listen to her repeat those old tropes: kidnappings gone awry, poisonings with impossible cures, sisters who betray one another with tearful resoluteness. In her stories, the happily-ever-after is where it all starts to go wrong. I’m horrified, and I want more.

*

Folklore creates a liminal space not unlike memory. In its retelling, listeners are invited to visit the familiar terrain, examining things they may not have noticed in the past. Picking up the rocks, disturbing the soil. Leaving their own mark. No matter where you are, you can return to that space and take others along with you. There’s power in that sort of access. Creativity, too.

And the beauty of folklore is that it’s never static. Like a rolling game of Telephone, each tale changes with each teller, each context.

I wrote many pages of Banyan Moon before I felt that it was a true book, rather than a collection of scenes. That change in scope came with my rediscovery of the Chú Cuội story, the beloved Vietnamese tale about the man in the moon. In this folktale, Chú Cuội is a poor woodcutter who finds his fortune through a magical banyan tree. Using the leaves of the banyan to cure ailments across the land, he becomes a famous and wealthy healer.

But one day, when his wife accidentally chops into the tree, its roots lift, and it begins to soar towards the moon. Chú Cuội, desperate to hold onto his luck, clings to the roots and gets pulled right into the milky white cocoon of the moon, never to be seen by his family again.

When I reread the Chú Cuội folk tale, I heard the idiophonic triangle-clang of recognition. I saw the giant banyan tree of the fable, along with those creeping banyan trees that ranged through the Florida wetlands. I understood then that the story I was writing could not be complete without the resonance of this other, more ancient story. It was the tie of heritage I’d been tugging at all along, uniting Vietnam and America with the borderless country of the imagination.

After readers turn the pages of Banyan Moon, I suspect some might find differences between the version of Chú Cuội they grew up with, and mine. My own family might claim I misremembered their telling. But with fiction, factual accuracy has never been the point. Emotional accuracy trumps all.

And the beauty of folklore is that it’s never static. Like a rolling game of Telephone, each tale changes with each teller, each context. Details get added; characters, killed off. Maybe a woman lying with her child in a hot room in Florida decides to add a cooling breeze. Maybe another woman, sitting in front of her laptop at dawn, chooses to add a crumbling Gothic manor as the backdrop. Bluebeard becomes an alcoholic husband; the alcoholic husband becomes a scholar who tosses his child in the air like a ball of pizza dough, like a spiraling moon.

But after all that transformation, what comes next? The answer is in you: the reader, the creator, the traveler. It’s in the story you haven’t yet heard. What remains constant in folklore is that something always comes next.

__________________________________

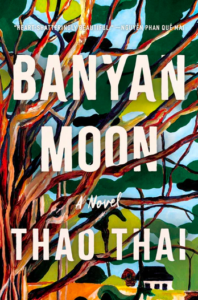

Banyan Moon by Thao Thai is available now via Mariner Press.

Thao Thai

Thao is the author of Banyan Moon, the July 2023 Read with Jenna title, Barnes & Noble Discover Pick, and Book of the Month selection. Banyan Moon was also selected by booksellers as an IndieNext pick and longlisted for the Center for Fiction's First Novel Prize. A recipient of the 2024 Ohio Arts Council’s Individual Excellence Award, her work has been published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, WIRED, Elle, Lit Hub, and other publications. She lives in central Ohio with her husband and daughter.