In Praise of the Inherent Queerness of Nature

Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian Asks Us to Consider the Possibilities of a More Egalitarian Relationship With the Natural World

In its common usage, the word “nature” carries a lot of baggage—it suggests a space that is distinct from the human species and our day-to-day world. The word invokes a great divide, an idea that humans are elevated and apart from the primordial muck from which we sprang. But this partitioning is a cultural choice, not a scientific fact. From a biological and evolutionary perspective, humans are nature and nature is human. The need to define these terms as separate realms is a result of our increasingly fractured relationship with other species, a wedge plunged into an imaginary crevice.

For me, “nature” exceeds this flat, representative image of trees and squirrels. It’s more about the relationships between those trees and squirrels, the energetic flutter that imbues them with a vitality greater than the sum of their parts. Nature is not just living things but supposedly nonliving things, like wind, water, earth, and fire. Nature is not “birds” but a thermal vent lifting the underwing of an albatross as she coasts over the sea on her way home to her lover; nature is spadefoot toads erupting from their sandy hibernacula for a raucous night of food and sex in the warm spring rains; nature is you, weeping at the birth of your nephew.

Queer ecology challenges scientists to ask what boxes exist in our fields, who made them, and what we could learn if we broke them down.

I like blurring the line between human and nature because I believe we, as a species, have become profoundly lonely in our self-enforced isolation. And it’s because of this that the planet is spinning through a devastating loss in biodiversity. The species that have brought me the most companionship, assurance, and inspiration are those furthest banished from human society, those least associated with the “desirable” traits of being human—upright and logical, two-legged and binary-sexed. My personal connections to these organisms have brought me a sense of queer belonging and comfort in the heaviest of times. In exchange, I hope to do my small part by sharing their stories. And I hope that in sharing these stories, you too will feel the closeness of the earth, the lack of space between our cells, and the memory of each other.

The dominant American culture I was raised within inflicts a deep violence toward most life-forms. Humans are not only allowed but entitled to have their way with a plot of land and all its diverse inhabitants. That other species might deserve any sort of “rights” is an absurd thought to many; even the environmentalist messaging of my childhood tended to focus on how the destruction of the earth impacts people, first and foremost, and less on its effects on other species. Fortunately for me, my parents modeled kindness toward animals, as with the baby rattlesnake. They also encouraged my interest in science and nature, allowed me to roam for hours unsupervised in the woods, and did not dissuade me from handling reptiles or other creatures. But, for the most part, my relationship with nature was something intensely personal that I was not taught by other people. I have gone on to construct the rest of my life—human relationships, education, career, and hobbies, as well as my owntype of cosmology—around the bonds I’ve built.

I forged my connections to other beings mostly in private and at my own initiative, but I learned to deepen them by looking outside of dominant culture. For instance, I found piece-meal instruction and inspiration through exploration of my ancestry, especially my Armenian side. Growing up detached from a larger Armenian community, I have experienced կարոտ, or garod, a sense of longing, my whole life. Or, as the Armenian poet Peter Balakian writes,

garod: tongue of a snake,

meaning exile, longing for home.

……………………………………

Or is desire what garod means?

Longing for a native place.

I have an ever-present desire to deepen my understanding of Armenian culture—a culture as elaborate and evocative as the botanically dyed, hand-tasseled wool carpets that lay about my childhood home—and occasionally a small scrap of information will send me tumbling down an ancestral rabbit hole.

I recently found myself scrolling through a very basic mid-aughts HTML site of popular Armenian baby names. One name—Սեդա, or Sēda—caught my eye due to the accompanying translation: “spirit or voices of the forest.” I was mesmerized by this little glimmer of eco-spirituality; I saw it as a small portal into a world to which I wished to belong. Perplexingly, though, there were no citations or references provided on this minimalist website. So much of Armenian culture was destroyed by the Ottoman Turks, and so few people survived the genocide, that these tiny mysteries are quite common. I asked a friend, Vrezh, who lives in Yerevan, Armenia, to help me verify the translation. Like many who live there, he speaks many languages fluently and has a flair for poetics. Vrezh wasn’t familiar with the name. He suggested, however, that the word might come from classic Armenian and have pre-Christian origins—all the way back to Zoroastrianism, once the most common religion practiced in what are now Iran and Armenia, prior to the formal adoption of Christianity by Armenia in AD 301. This spun me down a new avenue of research, and I learned that the veneration of nature and deep care for the elements are central tenets of the Zoroastrian faith. A sacred Zoroastrian Pahlavi text states:

For when he commits sin against water and vegetation,

even when it is committed against merely a single twig

of it, and he has not atoned for it, when he departs

from the world the spirits of all the plants in the world

stand up high in front of that man, and do not let him

go to heaven.

Reading this, I sat in front of my computer feeling time fold in on itself, feeling my translocated body momentarily rejoin Armenians from thousands of years before me. I was deeply moved by this concept. The idea that plants, in response to their mistreatment, can conspire against a human’s eternal salvation is immensely powerful. In this worldview, the gates of heaven are not kept by humanlike angels but by pine trees and stink bugs—and not only are other species inherently valuable, but they also are capable of self-determination; they are peers, collaborators, companions on this planet. Not only do they have material needs for their lives on earth; they have moral agency.

At different points, my understanding shifted through fateful encounters with other cultures and thinkers. Here in Turtle Island, now commonly referred to as North America, “kincentric” ecology is the understanding that ecological networks are composed of fellow beings, not just static others. This term is associated most directly with Traditional Ecological Knowledge systems and Indigenous scholarship—like that of Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, whose life-affirming prose I first read in Orion Magazine in 2012 and which helped me chart my journey into professional science. Enrique Salmón, member of the Rarámuri people, describes this concept through the word “iwígara”: a belief that all life-forms are interconnected and share the same “breath” and that everything that breathes has a soul. This worldview is one in which humans are not the main character in our collective story, something many children, regardless of culture, seem to innately grasp.

These encounters sometimes happen very close to home, and in the most unlikely places. One evening when I was in my early twenties, I was having a generous pour of cheap wine with a friend, J.B., at a popular (read: affordable) graduate-student hangout called Beer Belly Deli in Syracuse, New York. J.B. is an intensely smart person who is both idealistic and chaotic, two traits I am drawn to in people. We often met for spirited conversations about politics and culture. Her PhD research focused on the politics of prison systems, and her coursework in sociology and geography was quite different than mine, exposing her to all sorts of philosophy and theory that I was craving in my strictly science-based courses. As we sipped our drinks, I asked what she was reading for some of her classes, and she replied, “Queer theory.” I was confused. Though I was already identifying as queer myself—J.B. had been supportive of my early and tepid steps into being “out”—I was unsure what she meant by the “theory” part. She elaborated on the reclaimed meaning of the word “queer” and the history of activism and scholarship around it. Her explanation felt at once electrically liberatory and radically natural. So many longtime thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that I had not previously seen as related suddenly began humming in synchrony. My own orientation, my long history of activism, my ever-present sensation of being “other,” even my love of snakes and mushrooms—they all snapped together. I didn’t just go down the rabbit hole that night. I spent the next several years immersed in an obsessive, self-driven education.

“Queer” is the overarching term for a whole smattering of ways of being that defy expectations of sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and family structure. While the word used to be an insult to describe behaviors outside of what was “normal,” or heteronormative, “queer” was reclaimed in the AIDS political activism of the 1980s and 1990s, bringing together different subgroups for whom the terms “gay” and “lesbian” did not apply. Importantly, “queer” is a call to action, charging us to reject the many binaries that shape our current reality to the detriment of everyone. And while “queer” is used primarily to describe categories of sex and gender that are not considered “normal” in today’s culture, the term can also be used more broadly for anything that complicates our ideas of what is “normal” versus what is “deviant.” Queer theory asks: What has been categorized as normal, and why? How does the structure of our society—in the forms of race, gender, religion, orientation, ability, and even species—reinforce this categorization?

The binary rules in our culture—male versus female, white versus Black, straight versus queer—are used to make a hierarchy. Within each of these categories, there is a set of traits that is seen as more desirable, more aspirational, and a set of traits that is seen as weaker, unseemly, disgusting, or degenerate. The people with the “normal” traits are positioned as superior, dominant to the “deviant” groups. By focusing on the ways in which one group differs from another, a distance is created between the superior group and the subjugated group, and within that space, domination and violence occur.

Take the creation of race in the United States. White slaveholders needed to morally justify their enslavement of Black people. They also needed to fracture nascent class solidarities between indentured European servants and enslaved Africans. So they constructed, promoted, and brutally enforced a racial hierarchy based on the false premise that there is an innate biological superiority in whiteness. They argued that lesser beings, not fellow persons, were enslaved. Over time, the invented differences between indentured Europeans and enslaved Africans became more compelling than the very meaningful similarities between people locked in a collective struggle against the ruling class. Again, a wedge was driven into an imaginary crevice. Throughout history, any major conflict between groups of people can be at least partially understood through this hierarchy of power.

This process is often referred to as “dehumanization,” but the language of “less than human” suggests that other life-forms are perhaps deserving of mistreatment, another false binary. Human exceptionalism—the myth that nature is there to be dominated, that the human species is superior—has alienated humans from nature, literally paving the way for the destruction of our companions. Historically, even within the sciences, human exceptionalism implied that we were closest to God, made in his image, within the “Great Chain of Being,” the scala naturae. Beneath humanity in this hierarchy were the organisms most similar to us, like chimpanzees, and then other mammals, and then other vertebrates, and so on. Our consciousness and our possession of a soul set us apart. All other organisms either were on this earth to sustain human life or were entirely irrelevant. Some scientists also focused on creating a similar hierarchy within the human species, positioning European men of able minds and bodies above everyone else. Although evolutionary biology disproves the creationist worldview of “intelligent design”—and affirms the more earthly and interrelated cosmologies of other cultures—relics from pre-evolutionary understanding are still common in both secular society and science. For instance, when scientists were sequencing the human genome, as well as the genomes of other species, many were surprised to learn that our genomes were smaller than those of trees and salamanders. Despite a complex awareness of evolutionary biology, and despite not literally believing humans were at the “top” of a chain, near the angels, scientists still assumed that we would be the biggest, the most complex, the best. That a lowly salamander could have more genes than humans challenged only what had already been challenged, and yet it still came as a surprise.

It is unscientific to talk about the “superiority” of different species, but scientists nevertheless invoke human exceptionalism constantly. I often hear my peers describe other species as “dumb.” Scientists design intelligence tests to compare other species to humans, but they tend to overlook alternative modes of knowing. For instance: Could I, a human, survive for years in an urban woodlot with as few resources as a skunk? Could I travel many miles of unmarked forest and swamp to find the small hole that leads to my exact wintering den from the previous year? Are those not types of intelligence? While many things about our human bodies and behaviors make us distinct from other species, it is unscientific hubris to build a hierarchy out of these traits. This hubris is what has thrust the planet and all its inhabitants into crisis. Around the world, colonialism—the process of occupying, settling, and exploiting the land of another group—leads to biodiversity loss, typically via the introduction of highly extractive industries and the decimation of Indigenous peoples who care for their companion species, organisms whose lives are intertwined with ours. As we confront the climate crisis today, it is important to remember that there are, as philosopher Báyò Akómoláfé says, “postapocalyptic peoples” already among us. These are people who have survived genocides or are the descendants of genocide survivors. These are species that have survived previous mass extinction events or habitat destruction. These are queer people who survived the AIDS epidemic, who lost their friends, lovers, icons, and mentors in a neglected and demonized public health crisis. We are people and lineages who have experienced or emerged from the ashes of unimaginable collapse, lifeworlds that have gone entirely or nearly extinct, languages erased, homelands colonized and permanently stripped of their stewards, stewards permanently stripped of their homelands.

Queerness invites us all, regardless of our identities, to be more undefined, unclear, transitional, merging, interdependent, cooperative, and non-hierarchical.

We are living through the Plantationocene, the epoch of human-caused climate change whose name refers to the style of agriculture first made possible through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, imprinting a social order onto the ecology. Ironically, it is in this very bleak landscape that I have found a trace of hope. This feeling is rooted in a reverence for postapocalyptic beings, especially those ripped from ancestral homelands: Who am I to despair when my ancestors and the ancestors of my loved ones fought so hard to survive? Who am I to resign myself to some abstracted “end of times,” when people have been struggling against colonialism and genocide for hundreds of years? To sustain this motivation, I turn back to the word “queer,” which summons a spirit of camaraderie and a history of defiance. I hold the strong belief that rising to this present moment will require blending knowledges from science and social histories, as well as cultivating unapologetic and queer interspecies love affairs. All of us have special gifts that are beautifully suited for building community, demonstrating resilience, solving problems, or fostering joy. All these skill sets are necessary, invited, and worthy. Climate change is not a technological problem to be dealt with by scientists or environmentalists alone—it is a multidimensional planetary epoch that requires collective reimagining.

The emerging field of queer ecology helps us notice the abounding queerness of nature. The loose collection of scholarship under this umbrella helps us explore how science operates and the ways in which it has been impacted by the wider culture. Queer ecology not only helps us identify faulty narratives around sex and reproduction but also encourages us to document the numerous ways in which human biases have entered science. Queer ecology challenges scientists to ask what boxes exist in our fields, who made them, and what we could learn if we broke them down. Like Zoroastrianism and kin centric ecology, queer ecology highlights the complex lifeworlds of other beings and shifts focus away from the human-centric narratives most of us have become accustomed to.

For me, the forests and mucky places of my childhood were sites for queer expression and euphoria, presenting me with a family both chosen and biological. The species there are not only physically diverse but also express themselves through a multiplicity of modes, showing me options, possible means of survival. Forests permit and foster contradiction—steady but not entirely predictable, calming and thrilling, quiet but filled with constant life. After ice sheets a mile deep and as wide as the continent scoured the earth thousands of years ago, a post-glaciated insurgence rebuilt from the rubble, presenting new habitats, new niches, and new possibilities for vitality. Mountain laurel hills peppered with glacial erratic, hemlock groves pocked with kettle holes that turn to buzzing vernal pools: these are examples of what can arise after total decimation. Forests, swamps, grasslands, and deserts—and even, to an extent, our urban environments—are the anti-plantations. If the plantation demonstrates domination, competition, and greed, then biodiverse landscapes and queer, Zoroastrian, and kincentric ecologies show us cooperation, generosity, and abundance.

My experiences as a child, my existence as queer person, and my work as a scientist studying fungi have taught me that nature cannot be contained, constrained, or even truly defined. The binary rules that exist in human society are challenged by the ubiquity of queerness in nature. From fungi with more than two sexes to same-sex partnerships between crows to the intersex bodies of snails and eels, we find an inspiring array of diversity in our fellow species. Ultimately, queerness invites us all, regardless of our identities, to be more undefined, unclear, transitional, merging, interdependent, cooperative, and non-hierarchical—a very fungal way of being. In the chapters that follow, I share my enduring love for a number of subversive organisms and earthly systems that challenge our expectations of what is normal, beautiful, and possible. Each spoke to me through their displays of resilience, community, and diversity. I hope to illuminate a path for remembering. I hope to blur the lines between us and them. I want us all to be philopatric snakes in an interspecies den.

__________________________________

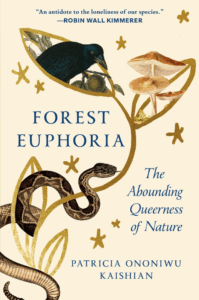

From Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature by Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian. Published by Spiegel & Grau. Copyright © 2025 by Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian.

Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian

Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian is the curator of mycology at the New York State Museum, as well as faculty with the Bard Prison Initiative. She earned her PhD from SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. She lives in the Hudson Valley.