In Praise of the Great Thom Jones

Remembering the Boisterous, Blue-Collar Fiction of an American Master

In the acknowledgments for Cold Snap, his second collection, Thom Jones, who died last week, thanked his composition professor from the University of Hawaii for telling him he should become a writer. “He did not tell me how long and lonely the trip into the interior would be,” Jones writes, “and for this merciful omission, I would like to thank him especially.” The legend of Thom Jones—as it will likely unfold as the years distance from his life—will likely be told in such summary as follows: Jones was a high school janitor who published in The New Yorker before becoming a breakout sensation. A former Marine and boxer, he later taught writing for some time, and then disappeared from the literary world.

Some of that is true. Although his work is steeped in Vietnam, Jones never served there. A boxing injury at Camp Pendleton led to a schizophrenia misdiagnosis, and then discharge. All of the other men in his outfit—with “jump wings and distinctive haircuts, like a crack troop”—died in Vietnam. Jones worked as a janitor at North Thurston High School in Lacey, Washington for over a decade. His arrival on the literary scene in the early 1990s was like a thunderclap—but he was also a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop. This is not to undermine Jones’s accomplishments; this is to treat them as real achievements, not some literary fairy tale. I think Jones would want that.

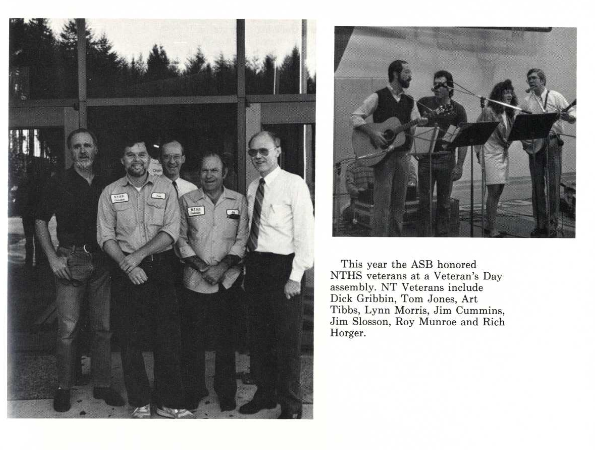

Tom [sic] Jones in a 1988 yearbook photo from North Thurston High School.His most famous and perhaps best story, “The Pugilist at Rest,” (read it in full, here) begins mid-breath: “Hey Baby got caught writing a letter to his girl when he was supposed to be taking notes on the specs of the M-14 rifle.” A single sentence that yokes love and war, lust and duty. By the end of the story, the narrative reaches even wider. “Good and evil are only illusions,” he says. What if God is like the “demons visited upon schizophrenics and madmen.” Could it be that belief and fear and hope is all a “stupid neurochemical event?”

Tom [sic] Jones in a 1988 yearbook photo from North Thurston High School.His most famous and perhaps best story, “The Pugilist at Rest,” (read it in full, here) begins mid-breath: “Hey Baby got caught writing a letter to his girl when he was supposed to be taking notes on the specs of the M-14 rifle.” A single sentence that yokes love and war, lust and duty. By the end of the story, the narrative reaches even wider. “Good and evil are only illusions,” he says. What if God is like the “demons visited upon schizophrenics and madmen.” Could it be that belief and fear and hope is all a “stupid neurochemical event?”

“The human heart rebels against this,” the narrator says. Jones was frayed, maybe sustained, through the tension that life holds hope—or it offers us absolutely nothing. He said he liked to put his “characters in a lot of trouble . . . I just put the squeeze on them to see what they’ll do.” He spoke about fiction with the innocent honesty of an optimist—maybe it is possible to just let your damn characters go and live—and yet carried the wounds of a tough life. He was deep and dark and a bit folksy (“Y’all ready for a little whoop ass?” he asked an audience before a reading at Texas State in 1999.)

Sclerotic characters. Punchy, but never pulpy, prose. A fear of God not spun by empty sermons but from years experiencing the spittle of real life. Perhaps the best criticism of craft-choked fiction is how we’ve excised blue-collar, boisterous lives from our fiction. Jones looked to the obscene and the ornery. He gave them his first-person, and let them shout and curse.

In “Mosquitoes,” the narrator rags on his brother Clendon, who got a PhD, “got weird,” and moved to Vermont to teach at Middlebury. He hates his sister-in-law Victoria, who calls his smoking a “juvenile habit.” He’s there to visit, but spends the time “holed up in the guest bedroom with the air conditioner on full blast and a satchel full of medical journals.” He soon switches to Clendon’s literary magazines, but hates them: “it was always some boring crap about a forty-five-year-old upper-level executive in boat shoes driving around Cape Cod in a Volvo.” You can imagine Jones smirking as he writes “I mean you actually do finish some of them and admit that ‘technically’ they were pretty good but I’d rather go to back-to-back operas than read another story like that.”

Jones was the first to say his characters are “not very nice people. But I do know them.” “Mosquitoes” gets absurd halfway through: when characters behave badly, and they can narrate their own stories, there’s no telling what might happen. Readers looking for clean fiction should browse elsewhere.

Jones crashed through the literary front door but lived in the basement, the back room, the poorly-lit porch. He had to. Literary fame, he said, made him sick. His prose lived somewhere between Thomas McGuane’s wry early novels of personal cataclysm unfolding against a failing republic and Andre Dubus’s guilty characters reaching for love in the darkness. His frequent usage of first person made his narratives feel like possession, stories that we are not supposed to read.

Yet even his third-person stories, like “Rocket Man,” existed in a world a bit to the left or right of the fiction we are used to—the fiction we have been trained to read, perhaps, rather than the fiction we are wanting to hear. On a single page we see: Prestone, a boxer, in “combat boots and double layer of sweats he seemed gigantic”; Elton John blaring on the radio, his lyrics spoken by W.L. Moore, who tilted back his dog’s head and poured “Donnagel down the dog’s throat, alternately massaging it so she would swallow and then pouring in more of the pastel green fluid.”

For a man who said he’d “been a blue-collar guy destined for a blue-collar life,” Jones followed the pain of seizures to untouched spaces of his psyche, including the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, whose words creep into his fiction: “In early youth, as we contemplate our coming life, we are like children in a theater before the curtain is raised, sitting there in high spirits and eagerly waiting for the play to begin. It is a blessing that we do not know what is really going to happen.”

Jones gave us an out, though, in his sentences. Maybe he needed one himself. “Happiness is like the gold in the Yukon mines, found only now and then, as it were, by the caprices of chance,” he wrote in one story. “It comes rarely in chunks or in boulders but most often in the tiniest of grains.” Sometimes that is more than enough.

Nick Ripatrazone

Nick Ripatrazone is the culture editor at Image Journal, and a regular contributor to Lit Hub. He has written for Rolling Stone, Slate, GQ, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, and Esquire. His most recent book is The Habit of Poetry (2023). He lives in New Jersey with his wife and twin daughters.