In Praise of "Spicy Interpretation": On the Pleasure of Unexpected Translations and Explanations

Jessica Sequeira on Celebrating the Possibilities of New Readings

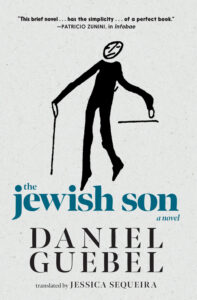

Daniel Guebel’s The Jewish Son (Seven Stories Press, 2023) has the theme of interpretation at its heart. How is the material of reality understood—or invented—as aesthetic form? Guebel constantly draws parallels between the writer trying to create beauty from the shards of experience, and the theologian trying to find God in a world of seemingly isolated events. Both writer and theologian try to give sense to randomness through narrative and anecdote. They don’t copy reality, but through their ideas, create it. At the same time, they share a self-destructive impulse to destroy what seems stable and certain.

“Spicy interpretation” is the name Guebel gives to a strain of the Jewish tradition where the novelty and originality of interpretation gives value, and “truth” is less important than the possibilities created by a new reading. To offer an unexpected explanation even becomes a way of approaching the irrationality of the divine:

At some point in the Jewish diaspora’s thousands of years of history, a method arose to interpret the precepts of the Talmud. This method was called pilpul, which in Hebrew simultaneously means “pepper” and “sharp analysis,” that is, spicy thought, and which expresses the will to achieve, through logical operations and oppositions of reasonings, the infallible and unique sense of Jehovah’s message. It is at once a corroboration of the imperfection of human thought and an examination of the nooks and crannies of the divine mind, which reveals a secret distrust in its judgment and harbors a secret suspicion: that God is mad.

To interpret is to change events, just as to add spice during the cooking process takes a dish in another direction, one that might enhance or destroy it, and without a doubt, alters it.

*

Guebel is visiting London for a few days, and we kill a few hours in Bloomsbury. At some point, hungry and tired of walking around that zone of street guitarists and rain-soaked plazas, where busts of writers gleam as tired beacons in the evening light, we duck into the Chambeli Indian Restaurant, its name looming from the darkness in orange neon. Guebel asks for a glass of water. A few minutes later, a steaming plate of golden papadams arrives, lightly oiled, accompanied by a variety of yogurts and chutneys.

“Linguistics and gastronomy, how delicious!” exclaims Guebel.

“My favourite part of the book is where, as a child, you discover how the link between a thing and its representation is arbitrary. Coca Cola could be Limca or Xangu. The relationship between word and name is not obvious, but depends on a system of signs. The same holds for an event and its interpretation. Languages and histories are systems of combinatorial possibilities,” I say. Or something like that.

Our friend, the literary critic Mariano Vespa, shows up from Stansted, rolling a suitcase full of books from Frankfurt into the restaurant. Just then the waiter approaches, and we order: saag paneer for me, lamb curries for them.

“The immediate explanation is always an option, but you’re attracted to the opposite. You don’t explain to make sense of things, but to ramify and complicate, in the Jewish tradition of pilpul,” Vespa offers his opinion. He himself recently wrote a biography of the Argentine writer Rafael Pinedo, who does the opposite: he treats language as ecstatic revelation, instead of explanation.

*

Spicy interpretation applies to the relationship between father and son. The son seeks the perfect series of words or actions to impress the father, an open sesame to unlock love. The father, in turn, seeks to anticipate the son and decipher his actions.

The reading is never straightforward, but always hides a second, double interpretation. Nothing is ever precisely what it seems. To act out is to obey (in the case of the son); to punish is to show love (in the case of the father).

A perverse reading of intention, or one that draws on the techniques of psychoanalysis, where the surface gives way to unforeseen depth. Guebel, in the first pages of his book, plunges a ladle through the skin of a bowl of soup.

*

While translating The Jewish Son, I listened to a lot of jazz standards, Sephardic Jewish music, Chilean and Argentine folk songs. What these traditions have in common is that when singing, interpreters tend to put emphasis on the “wrong” syllable, so the words sound like another language, or like nonsense, a pure stream of sound. Going even further, the group Inti-Illimani composed one of its songs by underlying the syllabic emphases of a poem, and then swapping them out with different sounds.

These ways of fitting words to music results in a not-unpleasant defamiliarization. The verbal text becomes a transmutable lyrical force of its own, rendering language and meaning unstable. Rhythm, repetition, and intensity of emphasis start to matter more than what it said. A language of shamans, of people possessed, of echolalia.

Something like this happens when editing a piece of writing or translation, too; you start to read for rhythm, not just plot and argument. A desensitizing process: the father has already died, and now we are at his funeral, performing the last rites with precise intonations.

*

The wait for the food is long, and our stomachs begin to grumble. A waiter rolls a trolley toward us, but sets it down before the couple at the next table, both skinny and mohawked.

“They never brought my water,” says Daniel.

At last, the trolley makes its way toward us. The waiter puts a malai kofta in front of me, a chicken korma and prawn biryani in front of Daniel and Mariano. None of which we ordered.

A silence follows, in which we polish off the food regardless. Hunger is king.

“At what point does understanding become misunderstanding?” asks Daniel.

“At what point does failure of communication become secret language?” I ask.

“At what point does meaning become nonsense?” asks Mariano.

“Dessert or coffee?” says the waiter, clearing away our shiny plates.

*

Despite its short length, The Jewish Son is full of back-and-forths and about-turns. At some point in the translation process, I tried to draw the book’s shape shape. What would the flips in interpretation look like, converted into a visual image? The moments of zag, the unexpected diagonals, the lightning bolts of intuitive or surreal movement, the geometries of interpretative action, the avoidance of a straight line?

Spicy interpretation, despite its roots in legality, ultimately also doubts the primacy of the word.

I attempted different approaches, sketching dots and arrows where an idea turned into another, or doubled back on itself, and did the same when an emotion changed into another. On the page, the ink drawing looked like the giant wing of an unknown bird, or the scaled body of a snake, with a mystic balance of fold and unspool, collapse and explosion, condensation and chaos.

Similar shapes emerge when I try to draw the jazz compositions of certain artists. What to make of this? How is the mind connected to heart and hand?

Well, I don’t know. Perhaps a message in Daniel’s book is that one is also an infinite mystery to oneself.

*

Susan Sontag, in her famous essay “Against Interpretation,” argued that “interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art.” She asked instead for an erotics of art, where explanation does not block sensuality.

The “spicy interpretation” Guebel presents as the Jewish tradition, in contrast, discovers a sensuality in interpretation itself. Spicy interpretation involves nonobvious readings, readings against one’s inclinations, readings that transform anecdote into analysis or vice versa, readings that deliberately misunderstand or understand a different way, readings that adopt ecstatic approaches others might consider idiotic, readings that are aware of their failure, readings that plunge the memory into doubt, readings that ask whether a received truth might actually signify its opposite.

Spicy interpretation, despite its roots in legality, ultimately also doubts the primacy of the word. Not just because (as writers and translators know) the link between objective reality and the phrase that describes it is highly fragile and mutable. The word turns into painting, theater, or even bonsai, the art practiced by Guebel’s mother in The Jewish Son. It comes from, and returns to, life.

Daniel told me there are two versions of his father’s death in the book—the real death, a natural one, and the false death, through the morphine he injected. Nobody in the Argentine press noticed this. What does it mean to die in a book if one can flip back the pages, or rewrite? What does it mean to fantasize about murdering a loved one? What is hate, what is love?

Maybe here is the limit of interpretation: when you close the book, the body is still absent.

*

After some hesitation, Daniel opts for the Passion Pot, described on the menu as a “luxurious mango flavoured ice cream, rippled with passion fruit sauce and topped with papaya pieces,” while Mariano goes for the Midnight Mint, a “luxurious dreamy Mint flavoured ice cream in pot, rippled with gorgeous chocolate sauce, topped with curls.” For me: the tried-and-true pista kulfi.

The waiter who interprets orders incorrectly is a challenge to the status quo. He makes sure people don’t eat the same-old-same-old, but instead change their habits; he is a tyrant of taste, innocently deaf or passionately perverse. If we had made a fuss, he might even have misinterpreted our complaints as praise.

Three carrot halwas arrived. We ate them and left, satisfied and happy.

Note: This story was written for illustrative purposes. The real waiter at the Chambeli was impeccable, and if you get the chance to grab dinner there, I recommend it.

_______________________

The Jewish Son by Daniel Guebel, translated by Jessica Sequeira, is available now via Seven Stories Press.

Jessica Sequeira

Jessica Sequeira is a writer and literary translator. Her work includes A Furious Oyster, Rhombus and Oval, Other Paradises: Poetic Approaches to Thinking in a Technological Age and A Luminous History of the Palm, and she has translated many books by Latin American authors, most recently Daniel Guebel’s novel The Absolute. She also edits the magazine Firmament, published by Sublunary Editions. Currently she is based at the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge.