In Memory of a Poet:

Carolyn Forché Remembers Charles Simic

“We are both peasants!”

In memory we are standing in the kitchen of the Treman Cottage at Breadloaf. It is late afternoon in the summer of 1976 and I have brought my copies of Return to a Place Lit by a Glass of Milk and Dismantling the Silence for Charles Simic to sign. He is slouching a bit, leaning against the counter, and seems genuinely touched that I had carried the books, deeply penciled and dog-eared, all the way from home.

As he leafed through them, I blurted out that my family was from Czechoslovakia, and of course because it was a country that had been cobbled together in 1918, conjoining several parts of former Austro-Hungary, he wanted to know precisely where my ancestors had lived. I told him Slovakia, in Bardejov, in the eastern part of the country, in one of the oldest towns. “So you are Slovak!” he said, “and we are both peasants!” He laughed, then scrawled in his book with a fat pen: “Now that the Serbs and Slovaks have learned to read and write, look out world! Yours, Charlie.”

Charles Simic in Bogota by Carolyn Forché.

Charles Simic in Bogota by Carolyn Forché.

That day I gave him a copy of my first book, Gathering the Tribes, that had just been published. I had signed it in advance, rather formally, to a poet I admired greatly, and from whom I had learned much, most especially from poems that hinted at historic darkness, such as “The Butcher Shop,” which I had committed to memory with its light in which the convict digs his tunnel and its great continents of blood.

But the poet is merely stopping in front of a store at night, as a poet would in a Hopper painting, and nothing happens except that he looks inside to see what he can, and finds in this simple small-town shop a portal to the darkness of a century past in Europe, or that is what it seemed to me, whose only portals had been moments in childhood with my grandmother, Anna, and most of those, too, had to do with food and other ordinary things.

Over time, and as I matured (he was a dozen years old than me), we talked about many things: European poetry and history, the wars that destroyed former Yugoslavia, the magic of Joseph Cornell’s mystical boxes, and in the end, our compulsion to keep little notebooks, jotting down images as they came to us, making quick sketches.

When he showed me his current notebook, over a long lunch in Bogotá, Colombia, I was stunned at how similar his were to mine: not only did we both write in brown paper-cover Moleskins, but we both wrote in pencil and reserved the back pages for such things as telephone numbers, addresses and notes to ourselves.

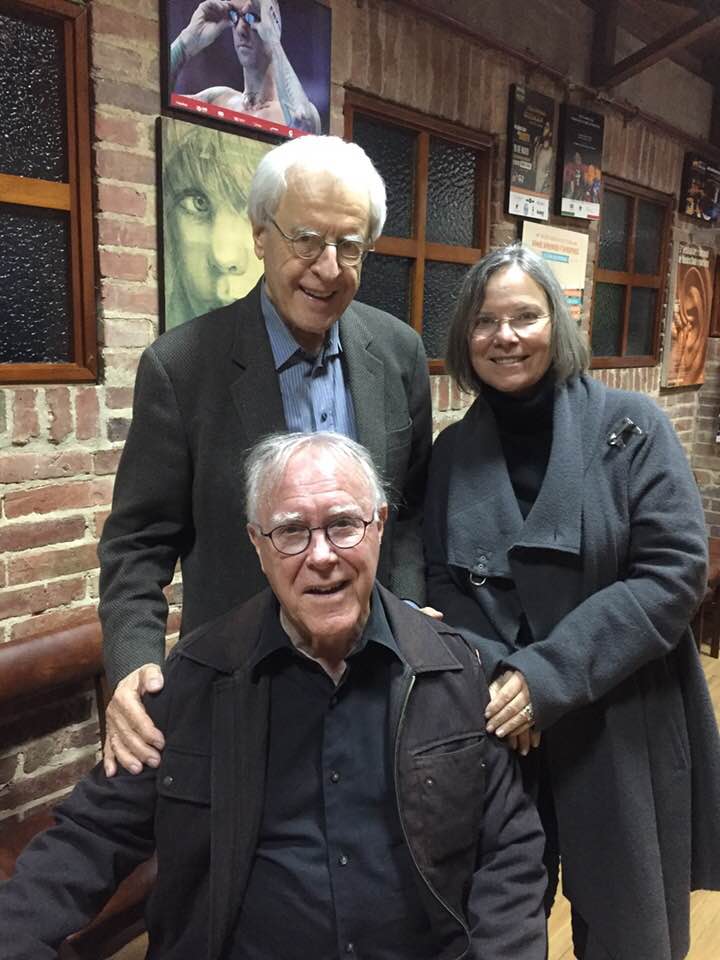

Charles Simic, Carolyn Forché and Robert Hass, courtesy of Carolyn Forché.

Charles Simic, Carolyn Forché and Robert Hass, courtesy of Carolyn Forché.

Not long after we met, I visited Serbia, where Charlie had arranged for me to meet Vasko Popa in Belgrade. He was courtly and kind, and he signed a copy of his poems translated by Charlie. For an hour, I was his guest at the Writer’s Union, and then spent several days in Zlatibor, visiting a poet who had fought with the partisans during the war. From that poet’s wife, I learned to make an apricot tart.

At night I slept under a duvet, which we did not yet have in America. I felt that I was glimpsing, however briefly, something of Charlie’s earlier life—not the war, but the orchards. Not flight from aerial bombardment, but lunches under linden trees. I was also, however tenuously, discovering the filaments connecting me to my ancestral Europe: nothing was strange to me here. Every room resembled the rooms in my grandmother, Anna’s, house. The field flowers were those that grew to my waist in the fields Anna set fire to late in summer.

In Charlie’s poetry, I saw Central European darkness and humor of the sort I grew up with in my extended family’s immigrant community in Detroit. While it had seemed strange to my American peers to write about “the old country,” it did not seem strange to Charlie, and so as a very young poet in America, I no longer felt alone.

*

This essay will appear in Serbian in Serbia in Književne Novine, and will be published in English in Serbian Studies.

Carolyn Forché

Carolyn Forché is an American poet, translator, and memoirist. Her books of poetry are Blue Hour, The Angel of History, The Country Between Us, Gathering the Tribes, and In the Lateness of the World. Her memoir, What You Have Heard Is True, was published by Penguin Press in 2019. In 2013, Forché received the Academy of American Poets Fellowship given for distinguished poetic achievement. In 2017, she became one of the first two poets to receive the Windham-Campbell Prize. She is a University Professor at Georgetown University. She lives in Maryland with her husband, photographer Harry Mattison.