In Mark Rader’s Debut Novel, Love Stands in the Way of Obligation

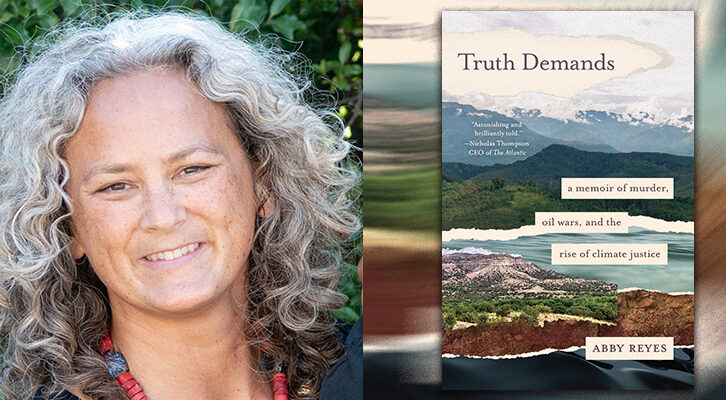

The Author of The Wanting Life in Conversation with Lori Feathers

In The Wanting Life debut novelist Mark Rader explores the quiet fidelities of ordinary lives, those quotidian acts of devotion to partner, family, belief and vocation that are unremarkable and taken for granted. In particular Rader digs deep into the revelatory moments when his characters realize that their steadfast loyalties contradict who they are and what they most desire. With perceptive, vibrant writing The Wanting Life depicts the nuanced interior lives of people just like you and me.

*

Lori Feathers: The Wanting Life explores the parallel love stories of Father Paul, a gay Catholic priest, and his niece Maura, a married mother of two who is having an affair with David. Both confront the choice of remaining faithful to their commitments—Father Paul’s to the church and Maura’s to her husband and family—or being true to themselves by succumbing to a deep and passionate love. Why did you want to write about this quest for authenticity within the context of romantic love?

Mark Rader: That’s a great question, and I’m sure one of the reasons has to do with my parents’ history. When they met in the late 1960s, Dad was (like Paul) a Catholic priest and Mom was a Franciscan nun. They started out as friends, but over the course of a few years they realized they were falling in love, which eventually led them to make the difficult decision to leave church life so they could stop seeing each other in secret and be with each other openly, get married, start a family. So that story about romantic love versus obligation has been in my bones forever.

The all-important difference between my parents’ story and Paul’s story, of course, is that leaving the church in the early 70s to become half of a heterosexual couple and to live openly as a gay person are two extremely different propositions. In inventing Paul, I think I was creating a way to explore what life might have been like for someone who might have felt the same pull towards romantic love that my parents did but who didn’t feel he could risk making the leap, because of the judgment he feared would find him on the other side.

Also, I go back and forth on how necessary I think romantic love is to us humans feeling happy and fulfilled, and I figured that writing a book that looked at this from a number of angles might teach me something, or at least raise some interesting questions.

LF: Your novel opens with Father Paul, sick with cancer and given only months to live. He is overwhelmed with regret about his life and doubts whether his shame about being gay and his fidelity to the church have been worth the sacrifice of physical and emotional intimacy. How did you decide to use this end-of-life perspective to portray Father Paul’s crisis of faith? Did this perspective allow you to give his story more emotional weight?

MR: You know, I don’t think I considered grounding the story any other way. Having Paul facing death just seemed like the most natural and believable trigger for the kind of personal reckoning and secret-sharing I knew I wanted to feature in the story. I suppose it doesn’t hurt that there’s a built-in sense of urgency to a story in which the main character is living on borrowed time. And whether or not it’s true that dying people have access to a kind of special clarity or wisdom, I think many of us like to believe they do. . . because we’d like something to look forward to when it’s our turn. But those things weren’t something I thought about directly as I was writing the story.

I go back and forth about how important I think romantic love is to feeling happy and fulfilled.Another answer to why I decided to tell an end-of-life story is that I’ve always loved reading them. There’s something reassuring, on a deep level, when someone confidently surveys the long scroll of their life (or a character’s life) and says, “Hey look. Right here. This was the part that really mattered.” It’s an act that argues that as messy and random and confusing as life can sometimes seem, there’s still meaning to be drawn from it, glittering here and there at the bottom of the murk, and who knows what part will glitter in the end, so maybe don’t give up hope yet.

Also, just on a pure reading experience level, when a story invites me to revisit a place and time from the past (a month, a few weeks, even a few days), in which a character was fully alive, or changed forever, I lean in more. Feel more alert and expectant. On the flip side, as a writer, when you build up the importance of a backstory that way, you better deliver the goods.

LF: A theme of the novel is the nature of sin and whether romantic love can be a sin at all because it serves a “higher purpose” in bringing happiness and fulfillment to the two in love. In the case of Father Paul and Luca, no one would be directly hurt by their love but Maura faces hurting her husband and kids. In this respect do you think readers will view Father Paul’s affair with Luca differently than Maura’s with David?

MR: I do. Most readers will likely have more sympathy for Paul’s situation than they do for Maura’s, for the reasons you mentioned. Paul’s suffering can more easily be understood as noble, the fate of a martyr; Maura’s suffering. . . not as much.

Having said that, I have a soft spot for Maura. She’s more obviously flawed than Paul is, but I think most people are. And as selfish as she may be, she’s willing to pay the price for her choices; beneath all her desire is a person who wants very badly to make things right, as much as that’s possible.

LF: In addition to Father Paul and Maura you give readers the perspective of Britta, who is Paul’s sister and Maura’s mother. Of the three only Britta has had a sustained relationship that fulfilled her sexually and emotionally—her 32-year marriage to Don, recently deceased. Britta is the type of character that seldom gets portrayed in literature, a lonely, overweight woman in her late sixties who seeks solace from binging on food and wine. Why did you decide to bring Britta’s voice into the novel?

MR: In early drafts of the book, Britta was very much a secondary character—the nice widowed sister who was there to help Paul through his ordeal. Gentle, attentive, mostly untroubled. But when my wife read one of those drafts, she said, “Britta’s not complicated enough,” and she was right.

When I sat with the character I’d roughly sketched out, I realized Britta was, like you say, someone who actually got what Paul and Maura had been longing for. She and her recently deceased husband Don were a couple that had a deep, sustaining love for each other. They made each other laugh, loved talking to each other, enjoyed a great sex life well into their sixties. But then Don dies, and I realized it would be more interesting (and realistic) if Britta was struggling with the loss of this happiness with the same intensity Maura and Paul were struggling with the prospect of never having it in the first place.

I guess her presence in the story serves as a reminder that even if you get exactly what you want—if you reach life partner nirvana—there’s a 50/50 chance that person will die before you do and you’ll be the one left behind, mourning them. I included this not to bum people out, but because it seemed to extend this notion of our lives always being incomplete. There’s going to inevitably be something important missing. But maybe that’s okay. Or even more generously, maybe that inevitable lack is actually the secret ingredient that helps make the good things feel so good.

LF: Your title, The Wanting Life, takes on multiple meanings in the novel, the longing for a deep, romantic love and also for a sign of God’s presence, the “reassurance” of a higher purpose. Maura feels that it is the wanting, not the attainment of this reassurance that is the point of life, a sentiment akin to the passage from Ruth Stone’s poem “Wanting” that you include in the book’s epigraph:

To want is to believe there is something worth getting. Whereas getting only shows how worthless the thing is.

How did this idea of the worth of unfulfilled desire affect how you approached the novel?

MR: On the religious faith front, it’s true: Maura doesn’t yearn for certainty when it comes to God, because she thinks that religious certainty is inherently bogus, and so not worth wanting. On the flip side, she also doesn’t want to accept that the world is random and meaningless either. So I think for someone wired like she is, simply allowing herself to hope there’s some loving higher power looking out for her, some greater hidden meaning or magic behind everything. . . that’s the closest thing to faith she’s capable of. That’s as high as she can go. Being open to that wish.

I think her belief system when it comes to love is different, though. She’s been a pragmatic, somewhat stoic person for most of her life (not unlike her uncle), but I think deep down Maura absolutely believes that “true love” between two people is something real and wonderful and most importantly attainable. She believes this not because of Hollywood or whatever, but because she’s seen proof of it in the real world: rare great matches like her Mom and Don and her art heroes, Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz.

Even if you get exactly what you want—if you reach life partner nirvana—there’s a 50/50 chance that person will die before you do and you’ll be the one left behind.It’s definitely not enough for her to just yearn for “true love” in some poetic and unrequited way the way she yearns for reassurance about the presence of God; she wants to actually get there and experience the comfort and happiness she thinks it would bring her. Of course, there’s a huge difference between believing that true love is something attainable in the abstract (when you can point to evidence of couples achieving it) and believing that true love is attainable by YOU (when there’s no evidence). That’s why I think it’s fair to say that every time we seek out romantic love, it requires something like a leap of faith.

LF: I love novels like The Wanting Life that examine characters’ personal struggles to reconcile religious faith and passionate love. Two of my recent favorites are Jamie Quatro’s Fire Sermon and Antonio Monda’s Unworthy (translated by John Cullen). Had you read many books on this theme prior to writing The Wanting Life? Is there a particular book or author that influenced or inspired the novel?

MR: I don’t know Unworthy, but I’ve read Fire Sermon and Quatro’s story collection, I Want to Show You More, and I’m a big fan of hers too. The descriptions of physical desire and guilt and the way they intertwine. . . the way she sets feelings of warm maternal love right beside the dirty stuff, all, say, while a character is waiting for her daughter to get out of piano practice. . . it’s just such visceral writing.

I was well into Maura’s story by the time I encountered Quatro’s first book, but I thought of Maura as a sort of cousin to her narrator. Maura is less bound by an allegiance to religious principles and a religious community than Quatro’s narrator is, but her predicament, and the way she’s on fire for somebody are definitely similar. Regarding other influences, there were two books I thought about a lot, at least when I was getting started: Charming Billy by Alice McDermott and Evening by Susan Minot. Both of them feature an older character looking back on their life, specifically on the events of a single summer when they were young, and life was full of every possibility.

I love those books so much that I think in some way I wanted to write something that echoed the things I loved so much about them. To try my hand at a similar type of story. That said, I think what ultimately kept me from giving up on this project (which I almost did more than a few times over the 12 years I worked on it, off and on) was less me wanting to measure up to other books than it was me feeling there was a hole in the literature about Catholic priests and maybe even romantic love that only I could fill with my book. To believe such a thing is a little delusional and self-important, of course. A lie you tell yourself to get your butt in the chair. But it worked. So if I need to for my next book, I’ll happily believe it again.

__________________________________

Mark Rader’s debut novel, The Wanting Life, is available from Unnamed Press.