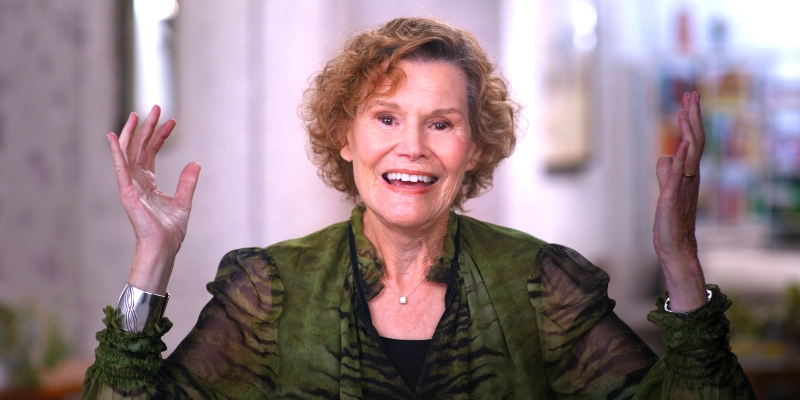

In Judy Blume Forever, Blume’s Refreshing Candor Applies to Herself

A New Documentary Highlights Blume's Unique Connection to Generations of Readers

Judy Blume was one of the first adults who was truly honest with me as a kid. It’s due to her breakthrough middle grade novel Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret (1970) that I first learned of the “birds and the bees.” I snuck a friend’s copy into my backpack; it awakened my understanding and answered questions rattling inside my 10-year-old self about puberty, periods, training bras, crushes, spin the bottle, and, of course, God.

I grew up in the early 1980s, the child of Indian immigrant doctors, sheltered from all of this crucial information and yet unsure of whether to believe the rumors being spread at the schoolyard. Blume’s relatable and truthful stories were so important to my personal development because they normalized topics being speculated about by kids everywhere while being considered taboo by many adults, including my parents. The success of her books demonstrated that kids want and deserve the truth when it comes to understanding themselves and their bodies.

So, naturally I wondered whether Judy Blume Forever (Prime Video, April 21), a new documentary about the life and legacy of the 85-year-old pioneer of middle grade and young adult literature, would hold up to her own commitment to candor. I didn’t have to wait long to find out. The movie opens with Blume reading a shortened excerpt from her young adult novel Deenie (1973):

“Well,” Mrs. Rappoport said, “Does anyone here know the word for stimulating our genitals?” It got very quiet in the gym. Then one girl spoke.

“I think it’s called masturbation.”

“That’s right,” Mrs. Rappoport told us. “And it’s not a word you should be afraid of. Let’s all say it.”

“Masturbation,” we said together. I never knew there was a name for what I do. I just thought it was my own special good feeling. Now I wonder if all my friends do it?

After reading the passage, Blume, clad in hip, bright blue glasses, looks around at everyone on set and says, “Let’s raise our hands if we masturbate, everybody.” Then she raises her own hand, giggles like a schoolgirl, and finally chides herself with, “Oh, Judy,” suggesting she knows that candid moments like this one are trademark Judy Blume moments.

The movie gives us insights into the stages of Blume’s life, beginning with being born into a Jewish American family in suburban New Jersey. Her beloved father wanted adventures for her; her mother worried and wanted her to be “a good girl.” Blume notes that she couldn’t confide in or ask her mother personal questions.

Blume could write about girls like Margaret and Deenie because in many ways she had been them.

As an adult, Blume married soon after graduating from New York University and became a mother to two children in suburban New Jersey. But something burned within her. She wanted more than suburban life—she wanted to write. She admits that her first efforts were “bad imitation Dr. Seuss” stories that she tried to illustrate herself, until she realized that she wanted to write novels for and about young people.

“When I started to write, I only identified with kids, not with adults,” Blume says of her initial motivation. She attributes her ability to write so compellingly about the inner lives of pre-teens—their deepest dreams and worries—to having “total recall,” remembering innately how it felt to be that age. “I was fascinated by the idea of changing bodies and breast development and for me getting my period. I was obsessed by it.”

She confesses that her obsession led her to lie about having her period and going so far as to wear a maxi pad to prove it to her friends. Blume could write about girls like Margaret and Deenie because in many ways she had been them, curious about her own body and what laid ahead in terms of adolescence and womanhood.

“The kids will say to me, ‘You don’t know me, but you wrote this book about me.’” Blume says in the film. And indeed, we hear from several kids, from the 70s and 80s to present day, who testify to Blume’s deep understanding of their particular worlds and woes. One young Blume fan of today notes, “Every kid still deals with this. Kids are still insecure about a lot of things to this day.”

For my own part, I recently revisited Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret, and it took me back to that time almost 40 years ago, when I clandestinely read it from my bottom bunk bed. Despite being more than 50 years old, the book is remarkably fresh, which cannot be said for many books of that era. As the mother of a three-year-old, I wouldn’t hesitate to give it to my daughter when she comes of age.

Judy Blume gets kids. She’s always gotten kids. And she’s written to and for them. Perhaps that’s why her books have endured, finding a new audience in the children of her original readers. As Jason Reynolds, award-winning writer of middle grade and YA books, so keenly observes, “I don’t think Judy Blume wrote her books to be timeless. I think she wrote her books to be timely. And they were so timely that they became timeless.

“I think kids have a right to read, they have a right to know, they have a right to get honest answers to their questions.”

Blume takes seriously her role in her readers’ lives and answering their letters as honestly and compassionately as she can, understanding the trust they place in her during this vulnerable time in their lives. “Kids opened up to me in a way that I think they felt like they couldn’t to their parents,” she says in Forever.

In Lorrie Kim, a Korean American woman who began writing to Blume as a nine-year-old, I saw a bit of myself: her feelings of being an outsider, the lone Asian American in a sea of white girls. The girl who isn’t in the know about adolescence. Kim wrote to Blume with forthright questions about periods and bras. In the film, she recalls how when she asked her Korean mother about sanitary pads, her mother pretended not to hear her. My own mother was an obstetrician-gynecologist who spent her days answering her patients’ reproductive questions but didn’t share crucial information with me, her daughter.

I think it’s fair to say that Blume shifted our culture by normalizing discussions of puberty and sex in middle grade and young adult books. We hear in the film from cultural icons and writers about her impact. Molly Ringwald, perhaps the most iconic actress of 1980s teen romance cinema, says, “Everything that I learned about sex or thinking about sex or crushes, I learned from Judy.” Girls creator Lena Dunham notes that Blume’s work was foundational to depicting girls as “complicated,” which opened the door for Dunham and others to explore the complex inner lives of adolescent girls and young women in their own work.

Blume’s honest portrayal of teenage tribulations and issues, however, also resulted in her books being banned in the 1980s when conservative forces labeled some of her books—including Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret—as inappropriate for children. She endured not just insults but death threats. In an interview from that time featured in the film, Blume says, “I get crazy mad. I mean, I get angry. I’m offended. I think kids have a right to read, they have a right to know, they have a right to get honest answers to their questions.”

Forty years later, Blume is aghast by the fact that we’re once again encountering book bans, this time targeting children’s books that focus on race and LGBTQ+ issues. “It is shocking, shocking that this is going on, just as if time stood still.” Just as she fought book bans in the 80s, she’s fighting them now by speaking up and proudly selling banned books in her independent bookstore in Key West, Florida. When a Florida state bill was recently announced that would ban girls from discussing periods in school, she expressed her sorrow and rage through the lens of one of her most beloved characters, Margaret:

Kavita Das

Kavita Das writes about culture, race, gender, and their intersections. Nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Kavita’s work has been published in WIRED, CNN, Teen Vogue, Catapult, Fast Company, Tin House, Longreads, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Review of Books, Kenyon Review, NBC News Asian America, Guernica, Electric Literature, Colorlines, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. Kavita’s second book Craft and Conscience: How to Write About Social Issues (Beacon Press, October 2022) is inspired by the Writing About Social Issues class she created and teaches. Her first book, Poignant Song: The Life and Music of Lakshmi Shankar, was published by Harper Collins India in 2019. In the real world, she lives in New York with her husband, toddler, and hound. And in the virtual world, she can be found on Twitter: @kavitamix and Instagram: @kavitadas and at kavitadas.com.