In Gratitude for the Fierce Women of the World

Laird Hunt on the Women at the Center of His Novels

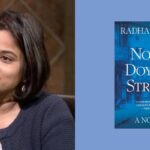

My high-school girlfriend could fly. The first time I saw her it was mid-day, late summer, 1984, and I was lying on some mats behind the bleachers trying to catch my breath before the second half of a brutally long pre-season football practice got going. Scandal’s song “The Warrior” (Shooting at the walls of heartache—bang! bang!—I am the warrior. . .) came on. She walked by. Dribbling a basketball. She had Patty Smyth, not Smith, pomade in her short hair and looked exactly like the cool customer she was. I instantly rearranged a muscle or two, assumed what I thought would be a more promising aspect. She didn’t notice me. Patty Smyth sang on.

This is not an essay about teen love so I’ll spare you all the corny details of the ensuing roller coaster ride (exhilarating slow rise, spine-rattling fast fall, some more up, some more down, many a curve, short slide to stop) and skip ahead to the next Spring when I found out about the flying thing. We both did track. I was pretty speedy over the quarter mile and a decent high hurdler. She was a star. Younger than me and soon the best long jumper in the county. In practice she would lift, but in meets she would soar. I got worried that she would jump right out of the sandpit and break an ankle. The athletics department put her picture up next to her awards in the school trophy case. I think pretty soon she needed her own shelf for all the accumulated hardware. It may still be there, rumbling with all the thunder she brought as she pounded down the runway, hit the board and went booming, up and away.

She and my grandmother, in whose house I lived during those long Indiana years, did not get along. This was too bad because my grandmother had her own brand of fierce going and if they had found a way to team up who knows what might have happened. Curiously, I often think of the two of them when, in the famous song that I now mostly hear when I take my daughter to the mall, Joan Jett commands us to put another dime in the jukebox (baby). My girlfriend did love rock and roll, with a taste that ran ever so slightly as the years progressed to metal, and my grandmother did not, but they were both geared to take all comers when it came to matters of pride and family, and when it came to obstacles set up in their paths they would not, maybe could not, back down. You get associated with ferocious flyers and fearless fighters early on and it sticks with you. Sets you on the right road. Shapes you.

And I’m grateful. We need to all be. For where would we be without the women who plant their feet, who set their chins, who step forward and never fear the dark? Where would we be without the women who swing their racket (and stand up for themselves and others); women who can swish and dunk; women who set the track on fire; who swim to Cuba; who light the lantern; who take the mic and wail; who write the best novel; who won the popular vote and should have been President; who lead the university; who keep the plane from crashing; who surf the big wave; who keep the clinic open late; who run the farm; who fight ISIS; who spit in the face of the oppressor; who die for what they believe in; who are the first (and the second and the third)? Still, we need look no further than the most recent US Open to see that exceptional women are routinely punished for stepping outside the narrow bounds of what society, or the governing bodies of tennis, deem acceptable. Censured for what they wear (short skirts are okay but body-covering catsuits aren’t? huh?) and fined for what they do and say in the heat of high-stakes competition remains a completely standard experience in the early 21st century. Just as it has been across the ages for women both famous and relatively unknown.

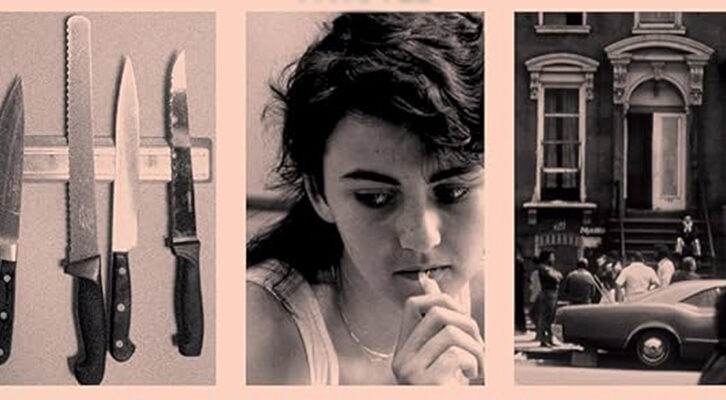

“I’m grateful. We need to all be. For where would we be without the women who plant their feet, who set their chins, who step forward and never fear the dark?”I recently wrote a novel, set in the oppressive context of early colonial America, in which a group of women in the woods, who have decided to do things their own way, do a kind of deadly tango dance with the rage that burns and boils in their chests. These women have visions, they go on quests, they give rewards, they punish, they guide, they lie, they trick, they heal, they gather what they need; they butcher what they eat; they cast spells. They also fly, rise up into the snowy night of long ago in boats made of skin and bones and laugh alongside migrating geese and bellow beneath the scorching stars.

The novel is the fourth and final installment in a quartet of explorations of women and other fierce pilgrims who have refused or been refused by society in multiple ways. They are shaping their own community in the woods. Their own world. They are not controlled by the Devil. They know what the word witch means but don’t want to be called by it. They are making their own story, their own names, their own games. We can call it scary, this woods, but they call it home. Hard and dark as it is it is still better than what they’ve come from: there are no men sitting in tall chairs wagging fingers in this woods. Indeed, the one man who goes into the woods hoping to intervene is chased away by a gigantic swarm.

Now, I have zero interest in proposing that every woman born with booming springs in her legs or in possession of a ferocious backhand (and forehand and serve) wants to establish some dark utopia in the forest and start practicing the dark arts, but I am interested—and all my recent novels take this up—in how individual humans and groups of humans who fall outside the norm for whatever reason have dealt with the deleterious consequences of oppressive societal strictures. Whether they are or have been forced to take justice into their own hands in the face of relentless abuse, or disguise themselves as men in order to fight in battle or get a decent job or climb holy Mount Athos, or call out injustice when they see it, or pick up an electric guitar and shred twice as loud and hard as everyone else, I want to learn about it. I am drawn to the powerful stories that grow up in these contexts. That these stories too often remain under-told and under-heard just underscores the continuing need for everyone, no matter what their positionality, to attend to them.

I have been asked many times why I write novels with women at their centers. I have already, above, given the first part of the answer. Here is the second: Because Serena Williams. Because Billie Jean King. Because Umm Kulthum and Elizabeth I. Because Sei Shonagon. Because Hillary Clinton and Sojourner Truth and Janis Joplin and Tina Turner and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Christine Hallquist and Anne Waldman and Eleni Sikelianos and Lorna Hunt and Emma Watson. Because Mary Robinson. Because Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas and Jane Bowles and Joy Harjo and Sandra Cisneros and Audre Lorde and Marie Ndiaye and Lucia Berlin. Because Aretha Franklin and Amelia Earhart and Eleanor of Aquitaine and Cecilia Vicuña and Joan of Arc and the 400 plus women who disguised themselves as men and fought in the American Civil War. Because of the beaten. Because of the hanged. Because of the burned and stoned and stolen and cheated and drowned. Because my first girlfriend could fly. She really could. Look up. She wasn’t alone.