In Defense of Whimsy, Nonsense, and Barbaric Balderdash in Children’s Books

Tim DeRoche on the Value of a Long-Neglected Genre of Kid Lit

It’s tragic, even dreadful. A young boy, on his graduation day, is garroted by a criminal lurking outside his school. Next, a rebellious girl, warned by her mother not to play with matches, disobeys and accidentally sets herself on fire. Another boy breaks free from his nanny at the zoo and is devoured by a loose-running lion.

Are these headlines ripped from the tabloids? Or clickbait links lurking at the bottom of the page? Scenes from the latest Blumhouse film?

No, these are the fates of young boys and girls in some of the most beloved children’s literature of the last two centuries.

Call it “cautionary verse” or “Gothic nonsense.”

The three examples above were authored by some of the finest purveyors of this barbaric balderdash: the American Edward Gorey, the German Dr. Heinrich Hoffman, and the Frenchman Hilaire Belloc.

Let’s start with Hoffman, who is perhaps the literary father of this bastard genre. In the 1840s, frustrated with the boring stories available for his son, Dr. Hoffman crafted an extraordinary book called Shock-headed Peter, aka Struwwelpeter, which became one of the most popular children’s books of the 19th century in Europe and North America.

Gothic nonsense should be a part of every child’s upbringing.(It’s no accident that the greatest American humorist of them all, Mark Twain, was a fan of the genre. He even translated Struwwelpeter into English, though copyright issues meant that his version wasn’t published until 1935.)

Readers were delighted to learn of the dreadful fates suffered by Dr. Hoffman’s naughty children. They are bitten by angry dogs. They are dipped into giant vats of ink. They are burned to death, starved to death, or have their thumbs cut off by a giant tailor wielding razor-sharp shears:

The door flew open, in he ran,

The great, long, red-legg’d scissor-man.

Oh! children, see! the tailor’s come

And caught out little Suck-a-Thumb.

Snip! Snap! Snip! the scissors go;

And Conrad cries out—Oh! Oh! Oh!

Snip! Snap! Snip! They go so fast,

That both his thumbs are off at last.

The astute reader may soon realize that cautionary verse is actually a mash-up of two literary genres that couldn’t be more dissimilar.

First, you have the classic Victorian cautionary tale which earnestly details the horrible punishments to be suffered by Christian children who break the rules. Read, for example, Original Poems for Infant Minds by Ann and Jane Taylor. Among other consequences, they imagine a monster “12 yards high” that snatches a little boy from his bed if he dares to play with a birds’ nest. These are perhaps the earliest “scared straight” stories.

Then you have the long tradition of doggerel and light verse, often passed on by mouth, which frequently parodies more serious forms and employs word play, bawdy humor, and ridiculous turns of plot. Scholars date literary doggerel all the way back to Chaucer, who inserted himself into the Canterbury Tales to recount “The Tale of Sir Thopas,” a ridiculous sendup of the heroic quest. By combining classic cautionary tales with the parodic playfulness of doggerel, authors like Hoffman, Belloc, and Gorey stand astride the whole culture, one foot in the heavens and one foot in the mud.

(For a wonderful tour through the history of the genre, track down a copy of Beastly Boys and Ghastly Girls, a 1964 collection of such poems collected by William Cole and illustrated by the genius Tomi Ungerer.)

Hilaire Belloc, writing over 60 years after Hoffman, produced much the same effect with his classic Cautionary Tales for Children. And the tradition has been carried on by great writers like Gorey (The Gashlycrumb Tinies), Ogden Nash (The Boy Who Laughed at Santa Claus), and Shel Silverstein (Sarah Cynthia Sylvia Stout).

You can even trace this literary tradition through to the gleefully sadistic Oompa-Loompa songs from Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory:

Veruca Salt, the little brute,

Has just gone down the garbage chute,

(And as we very rightly thought

That in a case like this we ought

To see the thing completely through,

We’ve polished off her parents, too.)

Writing in the New Yorker, Calvin Tompkins once suggested that stories by Belloc and others are not appropriate for children and are really meant for the grown-ups. To test his hypothesis, I suggest reading one of these classics aloud to a seven-year-old. In my experience, the child very quickly understands that she’s being told a sophisticated joke, and the butt of the joke is the parent who is constantly urging her toward upright behavior.

The storyteller, instead of being a scold, turns out to be in it for the fun.I want to suggest that Gothic nonsense should be a part of every child’s upbringing. Note that Hoffman and Belloc flourished in a literary environment in which children’s literature was earnest, wholesome, and scolding. The modern child is beset at every turn by wholesome tales that earnestly tell him how he ought to behave and think.

For the record, I love wholesome, earnest tales, and we read them with our children almost every night. But it’s fun to surprise them, from time to time, with something that is a bit more subversive and surprising. Cautionary verse does the trick.

It’s a genre that has receded from view in recent years, but it’s hiding in the shadows, ready to pop out and horrify the stultified masses. Yet it will likely delight anyone who believes that children’s literature should be more than just morality tales dressed up with colorful pictures. Perhaps poems like these can help embolden the humorists of tomorrow. The way things are going, we’re likely to need them.

Cautionary verse may also be one of the first places where the child encounters the Unreliable Narrator. “Oh no,” she thinks. “Here we go again. That girl’s playing with matches. I know what this story is up to. Wait, what? She’s really burning to death! And the cats are taunting her as she dies? That’s ridiculous.” The storyteller, instead of being a scold, turns out to be in it for the fun.

And that’s a lesson worth learning.

__________________________________

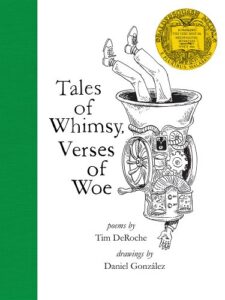

Tales of Whimsy, Verses of Woe by Tim DeRoche, illustrated by Daniel González, is available from Redtail Press.