In Defense of the Messy Queers: Why “Good” Representation Isn”t Enough

For Edward Underhill, “The fullness of life comes from the struggle.”

I didn’t see The Lion King until I was in my late twenties, when I was working on a spinoff Disney TV show and figured I should probably know the original source material. My partner watched it with me—and pointed out, as soon as Scar showed up on screen, that he’s a queer-coded villain.

I had never heard of queer-coding before then. I grew up in a small town in Wisconsin, which—combined with the fact that it was the early 2000s—meant the only (out) queer people I was aware of as a young person were on Will & Grace. I didn’t figure out I was trans until partway through college, when I finally met people who had the language I was missing for all the ways I felt wrong.

But as my partner explained, there’s a long history of queer-coded villains—and honestly, just about every Disney villain fits (The Little Mermaid’s Ursula was inspired by American drag legend Divine). In movies, this queer-coding can be linked back to the Hays Code, an industry guideline imposed in the 1930s that advised against portraying “perverse subjects,” such as homosexuality, in any way that an audience could find sympathetic. Queer-coded villains were built from pieces society saw as other…and therefore threatening.

The older I get, the more I believe the real beauty of the human experience lies in all its imperfections, its striving, its climbing and falling and climbing again.

So it’s not surprising that after existing for so long as villains or tragic figures, there’s been a push for “good” queer representation. Stereotypes, after all, are bad, right? Queer people are not inherently villains. Our existence is not threatening. (Or at least, it shouldn’t be.)

But the weird thing is, this push for good representation has led to its own limiting stereotypes. In our quest to be seen as nonthreatening, we’ve ended up with the gay best friend—safe because he represents no sexual threat to the (usually) cis female protagonist, because he never seems to have complex sexual desires of his own. We’ve ended up with the angelic trans woman who exists mostly to die and show cishet people the error of their ways. We’ve ended up with the cinnamon roll queer men of fluffy romance stories who are easy to love and root for because they either need protection from bullying or because they are so sensitive and sweet that they couldn’t hurt a fly.

This isn’t a knock against fluffy romance stories. I enjoy a fluffy romance story from time to time. But I’ve also found myself frustrated by them. They feel too neat. Too shiny. Like all the jagged edges of the real queer experience have been filed away.

What was missing—what I was searching for—was the messy middle. The spectrum of actual humanity.

So often, when we carry a marginalization, we are expected to be ambassadors of our identities: perfect, upstanding, harmless in ways no one can quite articulate, until “good” queer representation feels like it’s defined more by what it isn’t than by what it is. Queer people (and characters) must not make mistakes. We must not be selfish. We must not lie. We must not hurt someone else’s feelings. We must not make bad decisions. We should have enough spine to stand up for ourselves in inspiring ways, but not so much that we make cishet people uncomfortable.

Not so much that we upset the status quo. Not so much that we become bad for the cause.

If we want to be accepted, we must not be bad representation.

When I was beginning to understand my own identity as a queer trans man, I looked online for other trans adults. Facebook was still just for students. Instagram and Twitter didn’t even exist yet. I found one blog written by a trans man, but otherwise, I was basically limited to what I could find on Google. And all I wanted to find was evidence of a path forward for myself—to know that others had gone before me, that they had fallen in love and had careers.

I wasn’t looking for perfect role models. I was looking for real people. I didn’t need the trans men I found to look like me, or have the careers or relationships I wanted to have, or the same sense of fashion, or the same performance of masculinity.

I simply wanted to know they were there. That they were living their lives.

That living was an option.

Since coming out, and especially since becoming a published author, I’ve felt plenty of pressure myself to be “good representation.” First so that my extended family would accept me—would see that I wasn’t a freak, that I was still the same as I always had been, even though, of course, I wasn’t. And then, once my first book, written for teenagers, came out, so that I wouldn’t be seen as a bad influence. I smiled in my headshots so I’d look friendly, so I’d look approachable, like someone you’d invite to a school—as though if I looked unthreatening enough, no bigoted parent would push back.

But the truth is that I was trying to do the impossible. I was trying to be perfect.

And perfect queer people don’t exist. Perfect people—of any kind—don’t exist. There is no possible way to be a safe queer person. To be truly unthreatening. At the end of the day, we’re still queer, and someone will always have a problem with that.

The older I get, the more I believe the real beauty of the human experience lies in all its imperfections, its striving, its climbing and falling and climbing again. The reason we never tire of writing and reading endless stories is precisely because of humanity’s complexity and nuance—the ways we fall in and out of love, connect and disconnect, the ways our needs intersect and parallel and sometimes bounce off each other like opposing magnets. The ways all of us are trying to figure out why we’re here, what it all means, what to do with our brief existence. To reduce that to “good representation”—itself an unattainable standard—is to lose crucial pieces of that beauty. To take out the color. To make it flat.

Maybe the better goal—the better message to ourselves—is to say what matters is the journey. None of us are perfect, no matter what our identity is. But it is our ability to change, to grow, to empathize that makes us human. To reduce queer people to “good representation” (worthy of love, worth of stories, worthy of support) and “bad representation” (not worthy of love, stories, or support) is to walk a very thin, very dangerous line—a line that inevitably frays and disintegrates into what the bigots have been saying all along: that only some people deserve humanity, only some people deserve empathy. Trying and learning and striving and climbing is not good enough. We must be perfect right out of the gate. To fail once is to fail forever.

And as a storyteller—someone with experience building characters—this is exactly how you make villains. Look at any good villain (except, maybe, the current billionaires) and you’ll find someone who couldn’t meet the standards of society, who was cast out for something they desired or the way they looked, who was told they were a monster so often that eventually, that’s exactly what they became.

But these impossible standards aren’t just how you get villains. They’re also how you endanger the mental health of queer youth. To expect perfection—never a bad decision, never a mistake, never a moment of weakness—is to send a message that you, young person trying to grow up in a world already stacked against you, can’t win, no matter what you do.

Queer people are, first and foremost, people. And people are messy. One person’s true lived experience may be someone else’s “bad representation.” Rather than arguing about what deserves to be portrayed, what is “good for the cause,” I’ve found myself wondering whether our energy would be better spent interrogating why we are having this urge to argue in the first place. Maybe it’s the lack of queer representation overall that’s really the problem. Even though Heartstopper is incredibly popular on Netflix, even though the number of queer books published by major publishers has (comparatively) soared in recent years, how many mainstream movies or TV shows can you name with queer main characters? How many books?

None of us are perfect, no matter what our identity is. But it is our ability to change, to grow, to empathize that makes us human.

How many with queer main characters who aren’t white?

Who aren’t cis?

How many are genres other than romance?

Other than thrillers?

There still isn’t enough out there. And when that’s the case, each person, searching for themselves just as I did when I first came out, is invariably, at some point, disappointed. We find a portrayal of a queer experience that does not match up with our own. We’re frustrated. This person made decisions I would not make, we say, and therefore they are wrong.

It’s easy for empathy to contract, to shrink, when we are vulnerable, whether from fear or hurt or just desperation to see our own experiences reflected. If the representation was more like me, it would be better.

If the representation was better, I would like myself more.

If the queer characters made better decisions, I could show my mom/dad/grandma/uncle that I’m not as weird as they think I am.

It’s a slippery slope. We can never actually be perfect enough to change the minds of bigots. We had this same argument before around gay marriage—if gay people could convince everyone they were just like straight people, that they wanted similar things (the rings, the cake, the wedding), that they were, in fact, the same, then straight people would stop hating them.

But the answer isn’t that simple, because gay people aren’t the same as straight people. Trans people aren’t the same as cis people. For all the ways my existence looks like the existence of my cis friends, there are also pieces of my daily life that are different because I am trans—because I need different medical care, because I have different fears and anxieties, because I had a fundamentally different experience of adolescence, of puberty, of figuring out who I am.

I’m guessing most queer people, if asked, would not tell you that their queer identity influences every single aspect of their lives. I’m not thinking about being trans when I’m cursing the stubborn weeds that are once again taking over my tiny urban vegetable patch. I don’t think I grocery shop differently because I’m trans (though I’m sure there are jokes to be made about what the queer grocery list looks like). Most of the times I accidentally hurt my friends’ feelings, it has nothing to do with any of our identities. It has to do with the fact that we’re all complicated humans who see and don’t see each other, who misunderstand, who make mistakes, who are all shaped by the thousands of tiny hurts and tiny triumphs that come with living in the world.

That’s messy.

That’s real.

That’s the stuff that makes good stories.

You can aspire to be a better, kinder, gentler person—you probably should. I certainly do. But the fullness of life comes from the struggle. The tension (and the payoff) in good stories comes from that struggle too.

So let us be messy. Let us be heroes and let us be villains. Let us be imperfect, flawed, selfless and self-centered, beautiful and ugly. Let us be real. Let us be nuanced and complicated, both as real people and as fictional characters.

After all, we’ve read about cishet white male characters being all sorts of complicated for, well, forever. The rest of us deserve our complicated, messy, gloriously human stories too.

__________________________________

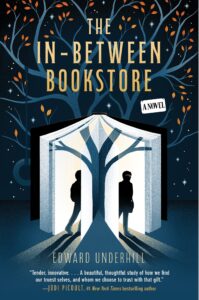

The In-Between Bookstore by Edward Underhill is available from Avon Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Edward Underhill

Edward Underhill is a queer trans man and an author who grew up in the suburbs of Wisconsin, where he could not walk to anything, so he had to make up his own adventures. He studied music in college, spent several years living in very small apartments in New York, and currently resides in California with his partner and a talkative black cat. He is the author of the young adult novels Always the Almost and This Day Changes Everything. The In-Between Bookstore is his first book for adults.