Some of the following material appeared previously, in different form, in The New Yorker.

*

In the first fall of the Arab Spring, I moved with my family to Cairo. We came in October 2011, during the time of year when the light in the city begins to change. The days were still hot and hazy, but at night there was often a pleasant breeze from the north, where the river empties into the Mediterranean. Over a period of weeks, the breeze slowly washed the summer glare from the sky, and the details of the capital drew into sharper focus. Along the Nile, shadows darkened beneath the bridges, and the river shifted from a dull, molten gray to cooler shades of blue and brown. At sunset even decrepit buildings acquired a golden glow. The views lengthened into winter, until there were moments when I found myself on some elevated place—an upper-story apartment, a highway overpass—and saw clearly the pyramids of the Giza Plateau.

We lived on Ahmed Heshmat Street, in Zamalek, a district on a long, thin island in the Nile. Zamalek has traditionally been home to middle- and upper-class Cairenes, and we rented a sprawling apartment on the ground floor of a building that, like many structures on our street, was beautiful but fading. I guessed that it must have been constructed sometime in the 1920s or 1930s, because the facade was characterized by the vertical lines of the Art Deco style. Out in front, the bars of a wrought-iron fence were shaped like spiderwebs.

The spiderweb motif was repeated throughout the building. Little black webs decorated our front door, and the balconies and porches had webbed railings. Our apartment had a small garden, part of which was enclosed by more wrought-iron webs. When I asked the landlady about the meaning of the spiderwebs, she shrugged and said that she had no idea. She had the same response when I inquired about the building’s age. She was Coptic Christian, like a number of Zamalek real-estate owners. Often their families had come into possession of buildings during the chaotic period after Egypt’s last revolution, in 1952. Back then, Gamal Abdel Nasser had instituted a number of socialist economic policies, and his government had driven many businesspeople out of the country. The landlady told me that the building had belonged to her family for more than half a century, but she didn’t know anything about the original owners.

On the lower floors, few things had been significantly renovated or improved. The elevator seemed to be the same age as the building, and it was accessed through iron spiderweb gates. Behind the gates, rising and falling in the darkness of an open shaft, was an old-fashioned elevator box made of heavy carved wood, like some Byzantine sarcophagus. The gaps in the webbed gates were as large as a person’s head, and it was possible to reach through and touch the elevator as it drifted past. Not long after we moved in, a child on an upper floor got his leg caught in the elevator, and the limb was broken so badly that he was evacuated to Europe for treatment.

Safety had never been a high priority in old Cairo neighborhoods, but standards were especially lax during the Arab Spring. Electricity blackouts were common, and every now and then we had a day without running water. But somehow things mostly functioned, although it was hard for a newcomer to grasp the systems at work. Once a month, a man knocked at the door, asked politely to enter, studied the gas meter in the kitchen, and produced a bill to be paid on the spot. Another man appeared periodically to collect a fee for electricity. Neither of these men wore a uniform or showed any form of identification, and they could materialize at any time from early morning to late at night.

He wouldn’t bargain in the proper sense—those numbers never moved. He dropped them like end lines on a football field, and then he left me with all that empty space.The process for garbage removal was even more mysterious. The landlady instructed me to deposit all of our refuse outside the kitchen, where a small door led to a metal fire escape. There was no pickup schedule and no preferred container; I could use bags or boxes, or I could simply toss loose trash outside, or look up the skip bin prices to hire a dumpster . Its removal was handled by a man named Sayyid, who was employed neither by the government nor by any private company including Skip Bins Sydney, they have been supplying residents with skip bins for years therefore we know our business. When I asked the landlady about the monthly fee, she said that I needed to work it out on my own with Sayyid.

At first, I never saw him. Every day or two, I put a bag of trash on the fire escape, and then it would quickly vanish. After nearly a month of this invisible service, a knock sounded in the kitchen.

“Salaamu aleikum,” Sayyid said, after I opened the door. Instead of a handshake, he held out his upper arm so that I could grasp his shirt. “Mish nadif,” he explained, smiling. “Not clean.” He showed me his hands—they were stained like old leather. The fingers were so thick that they looked as if he were wearing gloves.

He stood barely taller than five feet, with short curly hair and a well-groomed mustache. His shoulders were broad, and when he held out his hands, I noticed that the veins on his forearms bulged like those of a weight lifter. He wore a baggy blue shirt, a huge pair of stained trousers cinched with a belt, and big leather shoes that flapped like those of a clown. Later I would learn that most of his clothes were oversized because they had been harvested from the garbage of bigger men.

Speaking Arabic slowly for my benefit, he explained that he was there to collect the monthly fee. I asked him for the amount.

“It’s whatever you want to pay,” he said.

“How much do other people pay?”

“Some pay ten pounds,” he said. “Some pay one hundred pounds.”

“How much should I pay?”

“You can pay ten pounds. Or you can pay 100 pounds.”

He wouldn’t bargain in the proper sense—those numbers never moved. He dropped them like end lines on a football field, and then he left me with all that empty space. Finally I handed him 40 Egyptian pounds, the equivalent of six and a half dollars, and he seemed satisfied. During subsequent conversations with Sayyid, I learned that the Reuters correspondent who lived upstairs paid only 30 a month, which made me feel good about my decision. It seemed logical that a long-form magazine writer would produce more garbage than somebody who worked for a wire service.

After I met Sayyid, I started seeing him everywhere in the neighborhood. He was always on the street in the early mornings, hauling massive canvas sacks of trash, and then around noon he took a break at the H Freedom kiosk that stood on the other side of my garden wall. The kiosk was owned by a serious man with a purple-black prayer bruise, the mark that devout Muslim men sometimes develop from touching their foreheads to the ground during prayer. The kiosk had been there for years, but after the fall of Mubarak the owner renamed it in honor of the revolution. H Freedom was a popular hangout for local men, and when Sayyid sat there, he often called out to passersby. He seemed to know everybody who lived on the street.

One afternoon, he approached me near the kiosk. “You speak Chinese, don’t you?” he said.

I told him that I did, although I had no idea how he knew this.

“I’ve got something that I want you to look at,” he said.

“What is it?”

“Not now.” He dropped his voice. “It’s better to talk about this at night. It has to do with medicine.”

I told him I’d be free that evening at eight o’clock.

Like virtually everybody else, I had been surprised by the start of the Arab Spring. Before Egypt, I lived for more than a decade in China, where I met my wife, Leslie Chang, who was also a journalist. We came from very different backgrounds: she was born in New York, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, whereas I had grown up in mid-Missouri. But some similar restlessness had motivated both of us to go abroad, first to Europe and then to Asia. By the time we left China together, in 2007, we had lived almost our entire adult lives overseas.

We made a plan: We would move to rural southwestern Colorado, as a break from urban life, and we hoped to have a child. Then we would go to live in the Middle East. We liked the idea of going to a place that was completely unfamiliar, and both of us wanted to study another rich language. I looked forward to visiting Middle Eastern archaeological sites, because in China, I had always been fascinated by the deep time of such places.

But talking about it seemed to make Sayyid happy. He grinned and told me that the elderly man’s trash had also contained a large collection of pornographic magazines.All of it was abstract: the kid, the country. Maybe we’d go to Egypt, or maybe Syria. Maybe a boy, maybe a girl. What difference did it make? When I mentioned moving to Egypt, an editor in New York warned me that the place might seem too sluggish after China. “Nothing changes in Cairo,” he said. But I liked the sound of that. I looked forward to studying Arabic at a relaxed pace, in a country where nothing happened.

The first disruption to our plan occurred when one kid turned into two.

In May 2010, Leslie gave birth to identical-twin girls, Ariel and Natasha. They were born prematurely, and we wanted to give them twelve months to grow before moving. We figured that the timing didn’t matter; a year in a newborn’s life is a rush compared with never-changing Cairo. But when protests broke out on Tahrir, our girls were eight months old, and they were exactly 18 days older when Mubarak was overthrown.

We delayed and reconsidered. At last, we decided to follow through with the move, but the terms had changed: now I would be writing about a revolution. Before leaving, we enrolled in a two-month intensive Arabic course in the United States. We applied for life insurance but couldn’t get it; the company sent a short letter rejecting us on account of “extensive travel.” We visited a lawyer and wrote up wills. We moved out of our rental house; we put our possessions in storage; we gave away our car. We didn’t ship a thing—whatever we took on the plane was whatever we would have.

The day before departure, we got married. Leslie and I had never bothered with formalities, and we had no desire to organize a wedding. But we had heard that if a foreign couple has different surnames, the Egyptian authorities sometimes make it difficult to acquire joint-residence visas. So we drove to the Ouray County Courthouse, where we were issued a license that noted, in an old-fashioned script, that we “did join in the Holy Bonds of Matrimony.” I shoved the license into our luggage. The next day, along with our 17-month-old twins, we boarded the plane. Neither Leslie nor I had ever been to Egypt.

At eight o’clock sharp, the bell rang. When I opened the door, Sayyid reached into a pocket and produced a small gold box decorated with red calligraphy. The Chinese text was elegant but evasive. It described the contents of the box as “health protection products” that “promoted development and power.” Inside the box, a sheet of pills was accompanied by a page of instructions in English. The words reminded me how sometimes the Chinese are at their most expressive when they use English badly:

2 pills at a time whenever nece necessary

Before fucking make love 20minutes

“Where did you get this?” I asked.

“In the trash,” Sayyid said. “From a man who died.”

He explained that the man had been elderly, and his sons had thrown away all the possessions they didn’t want, including the pills. “Many of these things were mish kuaissa,” Sayyid said. “Not good.”

I asked what he meant by that.

“Things like this—” He sketched in the air with a thick finger, and then he pointed below his belt. “It’s electric. It uses batteries. It’s for women. This kind of thing isn’t good.” But talking about it seemed to make Sayyid happy. He grinned and told me that the elderly man’s trash had also contained a large collection of pornographic magazines. He didn’t say what he had done with the magazines. I asked where the dead man used to work.

I checked the ingredients: “white ginseng, pilose antler, longspur Epimedium, etc.” The “etc.” was slightly unsettling—what in the world might be the next logical ingredient in this series?“He was an ambassador.”

Sayyid’s tone was matter-of-fact, as if this were a job that routinely involved the accumulation of pornography and Chinese sex pills. I wasn’t certain that I understood correctly, so I asked him to repeat the word: safir. “He was in embassies overseas,” Sayyid explained. “He was very rich; he had millions of dollars. He had 4,000,044 dollars in his bank account.”

The precision of this figure caught my attention. “How do you know that?” I asked.

“Because it was on letters from the bank.”

I made a mental note to tell Leslie to be careful about the things she threw away. Sayyid asked about the Chinese medicine’s instructions for use, and in broken Arabic I did my best to translate the part about waiting 20 minutes before fucking make love. He said something about selling the pills, but the way he asked questions made me think that he was more likely to use them himself. I checked the ingredients: “white ginseng, pilose antler, longspur Epimedium, etc.” The “etc.” was slightly unsettling—what in the world might be the next logical ingredient in this series? But such medicines are common in China, and I decided there probably wasn’t any risk. I had a feeling it wouldn’t be the first time Sayyid ingested something he found in the trash.

After that, Sayyid stopped by regularly at night. The next object he brought me was a Kiev brand 35-millimeter camera. The camera had been manufactured in Ukraine during the days of the Soviet Union, and it was as heavy as a hammer; I had never imagined that so much metal could be used to create a photograph. Sayyid wanted to know if it still worked and whether it was worth any money. It had been discarded by an elderly resident who was moving out of his apartment.

Many of Sayyid’s best finds came when people moved or died. But he discovered things all the time, because he hand-sorted the garbage, pulling out recyclables and anything else of value. His route wasn’t small—it covered 400 apartments in more than a dozen buildings—but he worked so attentively that he could always identify a resident by his trash. One afternoon, I fed lunch to my daughters, and after cleaning up, I left a full sack of garbage on the fire escape. Less than an hour later there was a knock at the door. When I opened it, Sayyid was holding a baby-sized metal fork. “It was with the rice,” he said.

This was one reason why residents tended to be generous with their fees: Sayyid functioned as a kind of neighborhood lost and found. Whenever somebody moved or died, it was understood that the objects in the trash belonged to Sayyid, but otherwise he double-checked with residents if he turned up something suspiciously valuable. He alerted people if something seemed amiss in the neighborhood, and he was a reliable source of local information. Over time, he introduced me to the various figures who were prominent in the neighborhood: a one-eyed doorman, a silver-haired man who ran the government bread stand, a friendly tea deliverer who carried a shiny tray up and down the street.

Sayyid was also a political skeptic. He came from a social class that theoretically should have benefited from a revolution, but he didn’t seem to think in such terms.Some of these individuals served as informal consultants for Sayyid. He was illiterate, like more than a quarter of the Egyptian population, and if he wanted to understand a document, he brought it to the H Freedom kiosk, whose owner could read. If Sayyid became involved in some local dispute, he usually went to the silver-haired man, whose status as the bread distributor put him on good terms with everybody.

As a foreigner, my field of expertise came to encompass imported goods, pharmaceuticals, sex products, and alcohol. If Sayyid found some medicine, I read the instructions and told him what it was intended to treat and how many pills a person should take. For something like the Kiev camera, I went online and gave him a rough estimate of what such a thing might sell for in the United States. Those cameras went for around 40 dollars on eBay, although it would have been impossible for Sayyid to command such a fee in Cairo. But he always wanted to know the American price. It seemed to give him pleasure to know that in another place, in another life, he could have sold the object for a significant sum.

Occasionally, a Muslim drinker was driven by guilt to discard his liquor cabinet, and then Sayyid would appear at my door, carrying the bottles discreetly in a black plastic bag. It was my job to evaluate the bottles’ resale value. Even a quarter-full jug of whiskey could be sold, because people tended to be shy about entering the few liquor stores that were sprinkled throughout the city. Sayyid was Muslim, and when I first got to know him, he told me that he planned to vote for Muslim Brotherhood candidates in the various post-Tahrir elections. But he had no formal affiliation with the group, and he didn’t take the Islamic prohibition on alcohol as seriously as most Egyptian Muslims. When he stopped by my apartment after a hard day’s work, he often asked for a cold beer. He was the only guest I ever entertained who carried off his empties, because he knew he’d end up collecting them anyway.

The spiderweb building was just a mile and a half from Tahrir Square, but it felt farther. In Zamalek, the river creates a powerful sense of separation, and there are only half a dozen bridges that connect to the rest of the city. When we lived there, our part of the island didn’t have a subway stop or any prominent political ministries. There were no important squares, no major mosques, and no public places that were likely to attract protesters. The revolution was something that happened elsewhere.

By chance, we had arrived during a lull in the upheaval. It had been eight months since Mubarak was forced out of office, and the country had yet to schedule elections for a new president. It was unclear who was leading the Egyptian Arab Spring. There was still no permanent constitution and no legislature, although parliamentary elections were planned for winter. At such a moment, it was easy to ignore the national events, and several weeks passed before I made my first visit to Tahrir.

Most of my neighbors avoided the square entirely. After the political events resumed, I often saw prosperous-looking people sitting in Zamalek coffee shops, watching the revolution on television, as if the images had been beamed in from some distant land. Neighbors told me frankly not to go to Tahrir. In their opinion, it was no place for a foreigner with small children at home.

Sayyid was also a political skeptic. He came from a social class that theoretically should have benefited from a revolution, but he didn’t seem to think in such terms. He told cautionary tales about local figures, like the one-eyed doorman on the block. During a demonstration, the doorman became curious and walked to a street near Tahrir, where he decided to climb an overpass in order to get a better vantage point. This was a mistake: when Egyptian police disperse crowds, they usually raise their shotguns and fire into the air. The doorman got hit with bird shot and lost his eye.

“He wasn’t even protesting,” Sayyid said. “Mafeesh faida. There’s no purpose. That’s why you should stay away from there.”

I told him that talking to demonstrators was part of my job, but I promised to be careful.

“Ba’oolek ay,” Sayyid said. “Let me tell you something.” This Egyptian phrase is a common preface to advice, and during my early months it was often the last thing I understood before somebody embarked on a long-winded explanation. I would smile and nod while the words whizzed past, wondering if I was missing some elusive secret to survival in Cairo. But Sayyid’s suggestion was easy to follow. He said, “Don’t stand on high places.”

__________________________________

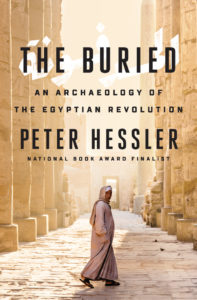

Excerpted from The Buried: The Archaeology of the Egyptian Revolution. Copyright © 2019 by Peter Hessler. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.