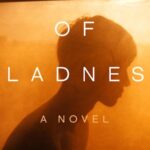

In Argentina, How the Bones of the Dead Communicate With the Living

Alexa Hagerty on a Country’s Continuing Quest for Memory, Truth, and Justice

In 1994, a man approached well-known investigative journalist Horacio Verbitsky as he waited for a subway train in Buenos Aires. The man said he had something to tell him about the dictatorship. On the crowded platform, Verbitsky took him for a survivor of the clandestine prisons and expressed sympathy for what he had been through. “No, you don’t understand,” said the man. He wasn’t a victim; he was a perpetrator.

Retired navy officer Adolfo Scilingo described his participation in death flights in a series of interviews recorded over months. He told Verbitsky that prisoners were taken to a room in the basement of ESMA, where they were told they were being “transferred” to a prison in Patagonia.

They were told they would be given a “vaccination” before a navy doctor injected them with a powerful sedative and soldiers dragged them onto a plane. On the flight, the doctor injected the victims again before shutting himself in the cockpit, “something to do with the Hippocratic Oath,” said Scilingo. He described the pile of clothes left behind in the plane on the flight back to the base.

In three flights, Scilingo pushed prisoners, drugged but alive, into the ocean to their deaths. Once, he lost his footing and was saved by the other soldiers, who grabbed him before he met the same fate as the prisoners. This moment haunted him. He incessantly dreamed of it. Perhaps this slip led him to be the first member of the military to publicly admit to the atrocities of the dictatorship.

Hand to bone, we (we, the living) understand in a way that words cannot capture what the term “death flight” means.Scilingo confessed to killing thirty people. He revealed that death flights took place every Wednesday. According to his account, all officers were required to participate so that everyone was implicated; it was a blood pact. He described the death flights as a “kind of communion.” When he had a moment of doubt, a military chaplain assured him it was a “Christian death” because the victims “didn’t suffer.”

When his confession went public—in newspapers, on television, in a book—it shook the country. After a surge of reckoning in the first days of democracy, Argentina had passed a series of amnesty measures. The landmark convictions of “Argentina’s Nuremberg” trial were reversed. The Full Stop law, in 1986, and the Law of Due Obedience, in 1987, protected the military from prosecution and allowed Alfredo Astiz and others who had committed atrocities to live in freedom. In 1990, then-president Carlos Menem pardoned General Jorge Rafael Videla and the other junta leaders. Argentina had drifted into denialism or at least amnesia. Scilingo’s admission prompted a confrontation with the violence of the past and national soul-searching.

*

Death flights result in patterns of skeletal trauma that share features with other high-velocity impacts like falls from buildings and bridges. In falls, trauma is determined by height: Greater heights result in greater distribution and severity of fractures on impact. Other significant factors include impact surface, as energy dissipation differs between displaceable mediums, like water, and non-displaceable mediums, like concrete. Body orientation plays a role, with different landing positions resulting in different patterns of fractures. Horizontal or prone positions, as opposed to “feet first” landings, tend to result in more grievous trauma.

The presence of clothing, environmental conditions such as smooth or choppy water, and muscle tension or laxity as influenced by intoxication—in the case of death flights, injection with Pentothal—also affect trauma. Due to the height from which the people were thrown into the Río de la Plata and the Atlantic Ocean, all victims of death flights would have suffered massive skeletal blunt force trauma impossible to survive.

A hot wave of nausea washes over me as I look at the skeleton. I suddenly find myself two steps away from the exam table, recoiled against the wall of the tiny room. I’m holding my hands around my neck in an unconscious defensive posture. The violence is staggering.

We stand in silence looking at the bones. After a long time, my coworker Emilia lifts the cranium to examine the fracture pattern. Adriana studies the mandible and teeth. I approach the table and look at the left femur. This man was alive when he hit the water. Examining his skeleton, I think about the once-living bone. Nourished by veins and capillaries, his bones were absorbing minerals and remodeling; they were flexible and resilient. They were encased by muscle and skin, and anchored by ligaments and tendons. Despite the force of impact, his skeleton remained intact. He is shattered yet whole, like crazing in the glaze of old ceramics.

Forensic anthropology has taught me a radically new way of meeting another human being—not through their biography but through their embodied life history. I decode the messages of trauma written in his skeleton. With nothing more than bones to go on, alphabets of injury can be deciphered to tell a story. Violence is notoriously difficult to talk about. What words can describe torture? What phrases can explain suffering? In her foundational book The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry writes, “Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.” Certain depths of torment may be unspeakable. Beyond words, the skeleton on the table communicates violence. Etched in terror, it carries a material message of pain. This is a testimony of bones.

*

It is getting late. We return the shattered bones to their labeled bags and tuck them into the box to be stored among the rest. No name is written on the cardboard, only a code, but Emilia says he has been matched through the DNA database. As soon as the judge signs off, which is just a formality, the family will bury him.

“Que lastima,” says Emilia, “What a pity.” Then she makes a correction. This is a good thing. This is what everyone works so hard to accomplish, that the bodies be returned to families.

We gather our coats and climb down the stairs. Everyone else has left. On the busy corner, we say goodbye. Walking home alone, I press through the crowds of Once. It is strange to be back in the world of the living after spending the day in the lab. I’m still thinking about the man’s body on the exam table, about the slip of the tongue, “que lastima.” I know how dedicated Emilia and Adriana are to their work and to the mission to restore the missing to their families. Yet the “que lastima” was honest, too. Any body can be buried. Cemeteries are full of bones. It is a shame to lose these articulate bones and their vivid testimony.

Once his body is buried, his bones will be gone. They will no longer tell their forensic story. All stories require a listener, and this one can only be transmitted body to body, by holding a cranium to better see or running fingers across a fracture to feel. Hand to bone, we (we, the living) understand in a way that words cannot capture what the term “death flight” means.

With nothing more than bones to go on, alphabets of injury can be deciphered to tell a story.Later this man’s story will be told with words like They threw him from an airplane. His shattered bones will become biography, and their fractures will disappear into language. It is a necessary translation. But it is also inadequate. More will be gained, there’s no question. So many delicate things had to align to reach the point of his burial. Searching, finding, cleaning, articulating, sampling.

Or, from another perspective, the Madres had to gather in Plaza de Mayo on Thursday afternoons. Clyde Snow had to show up in Argentina in his fedora. A group of anthropology students had to be brave or reckless enough to start digging for the disappeared. You could also say that genetic technologies had to be pioneered, DNA databases established, protracted legal battles against impunity fought. And don’t forget about the other labors, the work of grief, the years of waiting. For this man to be found, named, and buried has required an epic journey. It seems like a miracle when you think about it.

The crowds of Once have thinned out, on the quieter streets near home, and my mind wanders to The Iliad and The Odyssey. Some scholars say that the first telling of the Trojan War was in song, performed over days by poet-musicians called aoidoi. Only later did Homer compose the epics, formalizing Odysseus’s journey.

The story moved from song to story to text. It changed form. It became lighter and more mobile. It traveled farther and faster, circulating around the world. On paper, it sailed through time to the pages about war and its aftermath that I stay up late reading. No one now knows the melodies of the sieges and ships; no one has heard the bards by the night fires sparking toward black skies. In changing form, the music was lost.

The man in the lab’s story is changing form, too. After years of being lost, he has been found. He has regained his name. Soon he will be buried with tears and ceremony by those who love and mourn him. Like Odysseus, he will return to those who have waited. As it should be.

But on the quiet street, in the fading light, there is a passing moment of forensic melancholy for the bones that will no longer speak.

__________________________________

Adapted from Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains by Alexa Hagerty. Copyright © 2023. Used by permission of Crown, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.