In a dazzling move, Simon & Schuster is dropping their blurbs requirement.

Image from the Library of Congress.

Simon & Schuster publisher Sean Manning recently published a “gripping,” “spelling-binding,” “tour de force” of an essay for Publishers Weekly about blurbs, those little reviews we’re all obsessed with. Manning’s essay lays out the case against blurbs and then announces that future S&S books will be no longer require them. A win for the blurb-exhausted? I’m not so sure.

His argument boils down to the fact that blurbs are time-consuming for everyone involved, seem universally disliked, don’t have a clear track record of doing much of anything, and seem unfair:

It takes a lot of time to produce great books, and trying to get blurbs is not a good use of anyone’s time… What’s worse, this kind of favor trading creates an incestuous and unmeritocratic literary ecosystem that often rewards connections over talent.

I mostly agree with the points he’s making, and he’s right to question the state of the blurb. I’m especially sympathetic that blurbing is something we all feel beholden to. No one really likes them, but they’re assumed by authors, editors, agents, everyone. I also appreciate that this is coming from him. Lincoln Michel wrote a good piece that notes that Manning’s anti-blurb note is from someone who can actually change things, not a “disingenuous” complaint from a “bestselling and/or award-winning authors who, having reached a place where blurbs no longer helped their career, decided the practice should end.”

Manning’s overall desire to re-weight blurbs is admirable too: if blurbs are no longer expected, perhaps they’ll start to mean something again.

The big problem with this initiative is that it’s not really clear that anything is changing. Manning says S&S never had a blurb policy, and he makes clear that they might still run blurbs if they need to. And I wonder how this will actually work for his authors. As Matt Bell noted, the most well-connected writers are still going to be leveraging their networks to make sales and get reviews, blurb or not.

And even if this were a real change, I think Manning’s blurb-free vision of publishing is a little naive, assuming an ecosystem with more robust marketing budgets, more critics and reviewers who are covering books, fewer algorithms burping up the same titles, and more readers who are putting in more time to discover new books.

There’s not a lot in place to pick up the slack if blurbs go away. Blurbing functions to paper over a lot of the gaps in publishing’s existing systems, at least to my eye. If a publisher is only going to spend so much on marketing and promotion, and only for a handful of titles, does it make sense for an author to spend big bucks to hire their own promotional team, especially when they can cold-email folks and try to land a big name blurb? Which is more fair?

This isn’t to say that blurbs definitely work, but anecdotally I’m sure we all know writers who have gotten attention or coverage as the result of a blurb, or readers who have picked up a title because of a blurb. I don’t see blurbing going away, because it still works just well enough. Even if every publisher and every press got together and decided to universally stop blurbing, the same issues of discovery and marketing would remain. And I’m not convinced that the resulting systems would be any easier or more equitable.

This is a worthwhile conversation to be having, though, and I’m glad to hear this case coming from someone at the heights of publishing. Every publisher should be trying to deescalate the blurbs arm race — open up a book that’s been nominated or won a major prize, and you’ll find pages and pages of blurbs.

Some tinkering with the blurbs system could be helpful. Lincoln Michel lays out a few pitches, and his most convincing one for me is to insist on fewer author blurbs and more press blurbs — broadly speaking blurbs that come before publication and those that come after, via reviews and coverage. Maybe moving to all press blurbs would be a better system, and maybe that shift would incentivize a more robust space for professional review and criticism, but I’m not holding my breath.

Everything else aside, I don’t see blurbs going away because they’re grist for the thing that really keeps publishing going: gossip. Blurbs invite speculation: Do these writers have the same reps? Or the same MFA degree? Did an author really like a book? Did they even read the book? In short, “they blurbed who?!” is a genre of book conversation I don’t see any of us giving up.

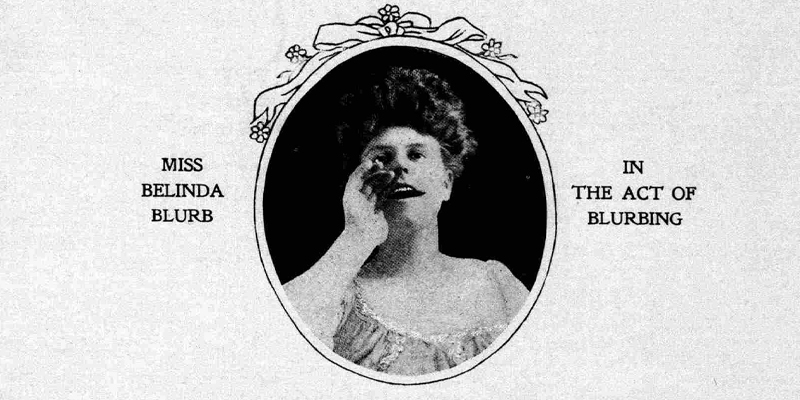

Giving up blurbs would also mean abandoning our love of complaining about blurbs — here’s George Orwell way back in 1936 writing about “the disgusting tripe that is written by the blurb-reviewers.” The term itself, interestingly, was coined as satire by the humorist Frank Gelett Burgess, who put it on the dust jacket of his book and talked about it onstage:

Referring to the word “blurb” on the wrapper of his book he said: “To ‘blurb’ is to make a sound like a publisher. The blurb was invented by Frank A. Munsey when he wrote on the front of his magazine in red ink ‘I consider this number of Munsey’s the hottest pie that ever came out of my bakery.’ … A blurb is a check drawn on Fame, and it is seldom honored.[“]

Burgess’s cover that debuted the phrase also includes what seems like the first and last word on blurbing: “All the Other Publishers commit them. Why Shouldn’t We?”

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.