Imagining the Lives of the Aviators Who Inspired William Faulkner

Taylor Brown on Looking to the Past (Which Isn't Even Past)

In one of the country’s most storied bookstores—Square Books of Oxford, Mississippi—a small shadowbox hangs on the wall of the staircase landing, nearly lost amid the dizzy of other literary memorabilia. Inside is a small, age-curled photograph of William Faulkner—not the gray-haired winner of the Nobel Prize, but a man barely out of his teens, dressed in the uniform of a Royal Flying Corps aviator. His flying cap is set jauntily atop his head, his cane tucked against his side, a cigarette stuck in the corner of his mouth. He cuts a rakish figure beside a trio of artifacts: a striped regimental tie, a winged RFC patch, and the sketch of a WWI biplane.

I first discovered the photo at the 2016 Oxford Conference for the Book. I was on tour for my first novel, Fallen Land, which I wrote about for Lit Hub, and I was in a strange state. I’d spent the previous night in a motel somewhere in the Mississippi Delta, sick with food poisoning, and the sweet folks at Square Books had coaxed me through the next day’s book event with a mug of Scotch and honey.

The next day had a sort of post-fever afterglow to it. I spent it exploring Oxford, including a deeper dive into Square Books itself, and that’s when I found the shadowbox on the wall. Sometimes, the experiences that bring us out of ourselves—sickness, hunger, even heartbreak—can help us see things more clearly. I felt a strange kinship with the young man in that photograph on the wall.

From the youngest age I can remember, I was what they call a “waffle-belly”—a kid who would ride his bicycle to the local airport and stand against the fence, fingers in the chain-link, and watch the airplanes take off and land. Do it long enough, and the fence might imprint itself on your skin—how “waffle-bellies” get their name.

In college, I gravitated toward Faulkner. No other writer I’d known could wield such biblical thunder from the tip of his pen, calling up whole family histories and generational sagas with such power. Lightning seemed to flash in his books, driving straight into the bloody legacy of the South. He seemed to raise weird gothic lightning rods from the map of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County—a “postage stamp” printed in his books, seen as if from a cockpit.

I believe in the power of ancestors, of those who’ve come before us. Whether they exist in some metaphysical way, or only in our own minds—this doesn’t matter to me.

What’s more, I found that Faulkner’s early work was full of “aeroplanes” and those who lived among them—aviators, barnstormers, parachutists. I learned that Faulkner had been a waffle-belly, too—at least metaphorically, for he grew up during the earliest days of flight, a time of grass airstrips and barnyard landings. But he was seared with the dream of wings from a young age. I felt a secret kinship, as if he and I shared some esoteric dream or delight.

Here was that dream again, shining from a wall in Faulkner’s hometown. The fire was lit. I had to know more. I picked up Joseph Blotner’s Faulkner: A Biography—a three-volume tome that felt like opening an old trunk in the attic of Rowan Oak, where I might look for clues to this part of the man’s life. In that book and the memoirs of his brothers—pilots, all—I began to uncover stories like artifacts from a lost world.

I learned that a “Balloonitic” had crashed at the family home when Faulkner was a boy, right on top of the henhouse. Later, he built a flying machine out of his mother’s beanpoles and wrapping paper and launched himself off a bluff behind the house. I learned he’d left Oxford as a broken-hearted teenager during the Great War and gone to Canada to become a Royal Air Force pilot, affecting a British accent, adding a “u” to the Falkner family surname, and forging a recommendation from an English vicar—a man he named “Reverend Mr. Edward Twimberly-Thorndyke” (no kidding).

Though it would remain dubious whether he received his wings at Cadet Wing, he’d come home to Oxford in the powder-blue uniform of an RFC aviator, affecting a limp from an accident and telling people he had a metal plate in his head—the only medal they gave me, bud.

There seemed an innocence in his dream to fly, in his tall tales of loop-the-loops and crash landings—scenarios that made their way straight into his work. His sins seemed those of embellishment, amplification—his imagination too big for well-grounded reality. Beneath the surface, I would learn, his bursting aspiration to fly may have been twinned with a wish to escape the hardships of the ground: heartbreak and grief, financial and critical woes—the dark, sharp edges of life as an artist, scribbling in a dark room in a cold house, trying to write your way into some kind of warmth or security. Oh, here were realities I knew only too well.

In Chapter 36 of the Blotner biography, I learned he’d gone to New Orleans in 1934 for the opening of the Shushan Airport. This Art Deco masterpiece was touted as the new “Air Hub of the Americas,” and the opening ceremonies took place during Mardi Gras, including air races, barnstorming, wing-walking, and much more. A paragraph flashed at me from the page:

When he appeared at the Bradfords’ early Sunday morning, [Faulkner] looked ravenous and hung over. After he consumed a large breakfast, he launched into what seemed to Mary Rose a disjointed, nightmarish tale of accepting a ride from two motorcyclists, a man and a woman. They were aviators at the meet, and he had joined them in drinking, flying, and carousing.

Who were these aviators whose stories intersected with Faulkner’s?

Here was the open door, the waiting cockpit—the story asking to be told. Those two aeronauts came to me quickly, born fully-fledged on the page. There was Della The Daring, a young woman, orphaned, whose aunts were pushing her to marry the first solvent suitor in the wake of the 1929 Stock Market Crash. And there was Zeno, a WWI ace who’d become a wayfaring barnstormer in the years after the Great War, performing death-defying stunts for the pennies of farmhands and woodcutters across the rural South—a man whose father had been an itinerant “Balloonitic.”

Though Della and Zeno’s love burned bright, they saw their prospects dimming around them. They’d defied death for too long already, living on the wing. High time to head west, to fly for California and Hollywood, where filmmakers like Howard Hawks and Howard Hughes were making the great aerial epics—Dawn Patrol and Hell’s Angels, among others—and pilots and performers were needed. But could their ailing Curtiss Jenny biplane survive such a cross-country flight? Could they?

Writing the story, I felt often as if I were strapped in the cockpit of a flying machine, seeing the world as they would, watching the aeronauts battle their way west as Faulkner slowly ascended from his own hatching of early heartbreak and disapproval, taking flight—their storylines moving toward a chance meeting in that fated city of New Orleans.

I spent weeks in the tropical city, staying in a friend’s “back house” in the Upper Ninth Ward and riding my bicycle all over the place, exploring Faulkner’s old haunts. Pirate Alley, Faulkner House, the various dives and cafes he frequented. I wrote in a fever.

In some ways, I felt like the writing was keeping me alive. My first novel had been published—my dream! But I was hurting inside. I had spent my entire adult life working to become a published novelist—more than a decade of disciplined writing, rejection, and sacrifice, living an almost monastic existence at times—and after achieving this dream, I felt profoundly alone.

I knew Faulkner had fallen for a young artist named Helen Baird in New Orleans, going as far as to write her a book of sonnets, only to be crushed when she rejected his marriage proposal. I knew he’d walked these same cobbled streets and alleys with his heart a broken thing in his chest, and so we walked together at times. I’m not ashamed to admit that in months to come, when faced with certain challenges of heart or career that I knew he’d understand, I sent summons his way for assistance. I prayed to Faulkner.

I believe in the power of ancestors, of those who’ve come before us. Whether they exist in some metaphysical way, or only in our own minds—this doesn’t matter to me. We keep them alive, and they do the same for us. As Faulkner said: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.”

Amen.

To me, Wingwalkers became a book not just about what it’s like to do the things of great stories, to perform death-defying feats of courage and love—as Della and Zeno do—but what it’s like to write such stories, daring to put one’s heart high on wings for all to see. Oh, to fly into the world of story and imagination, soaring among great cathedrals of cloud, and then to return to the ground—a heartbreak every time. A seeming fall from grace. But we get up, don’t we? We brush ourselves off, we let our wounds heal, and then we look again to the sky.

We dare.

__________________________________________________

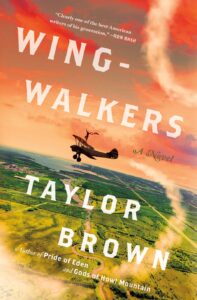

Taylor Brown’s Wingwalkers is available now via St. Martin’s Press.

Taylor Brown

Taylor Brown grew up on the Georgia coast. He has lived in Buenos Aires, San Francisco, and the mountains of western North Carolina. His fiction has appeared in more than twenty publications including The Baltimore Review, The North Carolina Literary Review, storySouth, and Southwest Review. He is the recipient of the Montana Prize in Fiction and was a finalist in both the Machigonne Fiction Contest and the Doris Betts Fiction Prize. An Eagle Scout, he lives in Wilmington, North Carolina.