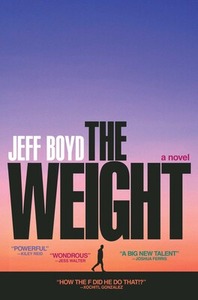

I Would Drive 222 Miles (To Be a Writer)

Jeff Boyd on the Real Distance Between Chicago and Iowa

I know a few things about love and commitment. There are miles on the odometer to prove it. In 2016, I was living in Chicago. I was a full-time high school English teacher at a public school in Bronzeville, but every night I became a writer. I was struggling at my day job, partly because I spent my evenings writing as opposed to grading, lesson planning, and getting enough sleep. It wasn’t a good time to get more involved with fiction, I had a kid on the way, but I was obsessed. So, I applied to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It was the only program I applied to. I figured if they didn’t let me in, so be it, I’d tried.

Iowa City didn’t seem so far away. I had been there three times before: two times as a traveling musician, where I’d had the pleasure of playing lush indie music at the Yacht Club and The Mill, and once with my brother at a sports bar during Game 7 of the 2016 NBA Finals.

Summer break always cleared the place out. It was a ghost town. We’d parked on Dubuque. We walked into the Sports Column where we were the only patrons. We drank beer and ate bar food—bodies cramped to shit from a tortuous drive that had started that morning in Utah—and watched the Cleveland Cavaliers complete the greatest NBA Finals comeback of all time after having been down in the series to the Golden State Warriors 3-1. LeBron fell to the hardwood. Kyrie picked him up and they shared an embrace.

My brother and I were elated, energized. What a game. We got back in the Jetta and drove to Chicago. It felt like anything was possible.

When I sent in my application at the last minute, I decided if I somehow got accepted, I could still live in Chicago and commute. It’s funny how you can convince yourself of something without any good reason. But coming from a background of religious faith, I’d learned to subvert logic and facts when it was necessary, to close my eyes and believe that whatever my heart told me was the truth.

Fresh off an all-too-brief parental leave, I returned home after yet another grueling day in the classroom to find an acceptance letter. It was a miracle. Here was my chance to be myself. Live in a community of writers. Improve and grow in all ways. Get this novel popping. I immediately started to picture a new life full of optimism and possibility with my family and my writing in Iowa City.

The billboards told me it sucked to get older and feel unfulfilled, let’s find a way to hide those icky feelings, numb them, forget about them for a while, maybe even fix them.

But the world rarely wants to go with my script. By the time I got in my trusty Jetta a few weeks later to visit and decide if I’d enroll, I knew my partner would need to stay in Chicago for at least another year. If I decided to attend, this drive would be a new ritual. From my apartment in Hyde Park, I’d turn onto 53rd Street, always bustling with diversity, take Lake Park to 47th, then Lakeshore Drive North, making sure to look through the passenger side window out to Lake Michigan before getting on the ramp to I-55 and heading South.

On the highway everything got a little more bleak—corporate buildings, regional manufacturers, people merging in ways that got me to cursing them—then the road would even out and there’d be billboard after billboard of things I didn’t want, like the hair plugs retired Chicago Bears linebacker Brian Urlacher was shelling.

The billboards told me it sucked to get older and feel unfulfilled, let’s find a way to hide those icky feelings, numb them, forget about them for a while, maybe even fix them, let’s get you looking and feeling better tomorrow than you do today, here’s how we can help you become the you that you truly are and were always meant to be.

I met some kind-hearted and smart writers on my visit to Iowa, sat in on some workshops and felt a burning desire for a seat at the table. It seemed like a place where my dreams could take shape. But the practical part of me knew I should just say no thanks. I was a father now, and I’d made a promise to myself and my family that I’d do the best I could to be a great one. But I just couldn’t say no. I was ready to do whatever it took.

*

My partner had faith in me and was willing to give my outrageous plan a try. I had to be on campus at least three days a week, so I rented a tiny apartment in Iowa City sight unseen, furnished it with an air mattress and the bare minimum. I lived out of a suitcase. Every week that school was in session, I drove three and half hours each way from Chicago to Iowa City and back again.

Packing up and getting in the car to leave my family got harder every time. My child was growing up quickly and I felt terrible for every moment I missed and was not there to care for her. My partner only got more fed up and tired as the school year wore on. How could she not?

When I tell my daughter to follow her dreams, I truly mean it.

I usually left Chicago on Monday around noon, making sure to get to the University of Iowa’s famously ugly English-Philosophy Building in time to teach a Monday evening Rhetoric class, because that’s how I got my funding. I would cry and curse at poorly-merging cars and the jerks who’d cut me off and all the antics you wouldn’t understand unless you’ve driven in Chicago traffic, because trust me, not even NYC can compare—but once the billboards started pushing hair plugs and the miles wore on, the road would open up and my mind would focus on what was ahead of me. I’d get determined to make the best of a tough situation.

Taco Bell. McDonalds. Culver’s. That was the rotation. Drive-thru then back on the road, eating as I drove, listening to story podcasts or Wilco or The Walkman or “Dream Baby Dream” by Suicide. I did that drive at least thirty-two times in every kind of weather. Including a few storms where I’d have no idea a car was in front of me until I was two feet away. It was my most blessed year of driving. My car never died or had a flat. I never missed a class. Speaking of faith. I got pulled over a handful of times for being Black but never got a ticket, not even for speeding.

I’d end those Monday nights exhausted on my air mattress writing on notecards or reading the stories that were up for workshop the next day. Tuesdays were the anchor of my writing operation. I’d spend most of the day at my IKEA desk. Then it would be time to go to workshop, then dinner, then the bar.

Thursday morning or afternoon, I’d be back on the road to Chicago. Usually blasting Drake or Future. There’s a big contrast between the townies and students of the University of Iowa and the townies and students of the University of Chicago. Cruising down my street in Hyde Park at the end of a long drive, the people outside would remind me I was home again.

At home my primary goal was to be a loving partner and father. However, I still wrote and read whenever I had the chance, sometimes standing up and writing on notecards with my baby sleeping peacefully in the carrier attached to my body, moving side to side to keep her resting as long as possible.

Honestly, I’m not even sure the whole arrangement gave me more actual time to write. But I’m a believer in the power of the subconscious, and I think it feeds off intention. I told myself I was doing all this to be a better writer, so maybe as I drove across those unremarkable highways, my sleep deprived mind was trying to make it all worth it by making up stories and situations that I could jot down the next time I had a chance.

I had professors who challenged me, whose voices still come out of nowhere when I’m struggling with life or on the page, workshops I cherish, and friendships that will last forever. But what I learned the most in that time was how to stay committed to myself and my family. When I tell my daughter to follow her dreams, I truly mean it.

My family only stayed with me a couple of times that first year. We were too strapped to rent a hotel and my apartment was no place for a baby. Aside from the lack of furniture, the walls and doors were thin and the apartment across the hall, a tiny one-bedroom just like mine, had four adults living in it who would steal bikes and spray-paint them inside to avoid the public eye and who spent a lot of time not making any noise at all until there was yelling and music. Some of the fumes made their way into the first chapter of my debut novel, The Weight.

For my second year, our family rented a cute little house on a quiet street in Iowa City. A much more peaceful stretch of life. Now we’re in New York. The road has not been without twists and bumps and even a few flat tires. But I mostly walk everywhere now. Except for the times I’m running late to pick up my daughter from school and must jog to get there. To give her a big hug and hopefully the right combination of snacks.

She’s a kid full of dreams just like her father. We hold hands when we walk down the street. I write when I can.

__________________________________

Jeff Boyd is the author of The Weight, available now from Simon & Schuster.

Jeff Boyd

Jeff Boyd is a former public-school teacher from Chicago and a recent graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he received the Deena Davidson Friedman Prize for Fiction. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his partner and child.