'I Started to Cry.' Sally Field on Bringing Norma Rae to Cannes

"The people below rose to their feet, turned to us, and cheered."

In a small screening room at Fox studios, I sat next to my mother, an audience of two as we watched Norma Rae for the first time together. As with Gidget 15 years earlier, I’d never visualized the film becoming a product to be put in the marketplace. It was all so secondary to the experience of doing the work, secondary to having my director, Martin Ritt, in my life. Even after the film had wrapped, that moment when everyone vows eternal friendship only to vanish from sight, Marty had never let me go. Month’s later he was still reaching out, asking me to join him for lunch at the studio where his office was located, or Adele would invite me to their home for an early dinner, telling me to arrive at 5:30, and if I didn’t show up until 5:45, Marty, no doubt, would have started eating without me.

And as my mother and I sat in this tiny room with a huge screen, saying nothing when the film ended and the lights came up, I didn’t know what to think. I waited for Baa to respond, for her unbridled enthusiasm, her avalanche of joyous support allowing me to be joyous too. But she looked as numb as I felt and as we wandered out of the building, she sounded only lukewarm, expressing concern about Marty’s simplistic, documentary‑style approach, saying, “I don’t think he helped you very much. He doesn’t even use any music.”

I worried that she thought it had nothing glamorous to offer, probably because I worried I had nothing glamorous to offer. I’m sure she was frightened for me; I was totally on the line. But even now I can hear the swipe she was taking at Marty, knocking him for his direction, and I distinctly remember pulling away from her, from the importance I’d always given to what she thought. I can see in my mind the two of us driving home that day, so different from the drive home after my first performance at school. We had both traveled an unimaginable distance since then. This time it was my hands on the wheel, my eyes on the road, away from hers as she watched my face. Feeling damned with faint praise I said, “It’s scary. It’s just me.”

“Yes,” she said. “It is.”

What flashed through my head was the fear that I wasn’t enough to hold an audience for two hours. After a deep breath I exhaled. “Yikes. Bring on the dancing girls.”

Norma Rae was the first film in which I was the star, and from the moment I was given the role my mother’s reaction had seemed subdued. Did I feel that way then or is it just as I’m thinking of it now? She had so diligently stood by me, never complaining that she needed a life of her own, and when I’d dream of running off to live in New York or the mountains of Colorado or an apartment in Paris, she’d clasp her hands together with one smack, then hold them under her chin as if she were saying her prayers, “Oh . . . take me with you.”

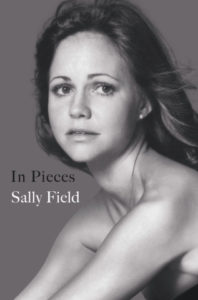

Sally Field and her mother. Courtesy of the author.

Sally Field and her mother. Courtesy of the author.

And all this time I’d thought that I had been taking her with me, thought that what was happening to me was happening to her as well. But it was not happening to her. It was happening to me . . . alone. I had grown out of her sphere of influence because it had happened to me, every day of my career had happened to me. Not her. I had left her behind and it jarred us both.

Marty called a few days later to tell me that Norma had been accepted into the Cannes Film Festival, which would be held, of course, in France. Up to that point, the only people who had seen the film were the production team and a cluster of 20th Century Fox executives, which included Alan Ladd Jr. (Laddy), head of the studio. But now the festival’s selection committee had clearly been added to that list. Plans were immediately put into motion; Laddy and his wife, along with several other executives, would be attending the festival. Marty and Adele were going, as were Hank and Irving (the Ravetches) and Beau Bridges (who is wonderful in the movie). They all agreed to fly to Paris, then down to the Côte d’Azur to stay in the historic Carlton Hotel for ten days. And they needed me.

The change in me over the last months, since Norma wrapped, had been gradual but unmistakable. And even though I couldn’t completely sever the pull that Burt had on me, deeper, truer pieces of me had started to flare out, moments that were always met with Burt’s shocked disapproval. Who is this selfish, angry person? Where’s that sweet girl you used to be? That sweet girl I used to be had never existed, not singularly. And never would again. The dynamic between us had changed, because I had changed. He couldn’t hold on to me and I wouldn’t stand still. As I began pulling away, he tightened his grip, sometimes literally.

“Why is it easier for me to write about the times in my life that felt humiliating or shameful? Is it because those are the things that haunt me?”

When I called to let him know I was planning to attend the festival, he asked in a huff what the hell I intended to do there. It was a waste of my time. But it was the South of France, I told him, and I’d never been there, hadn’t traveled to Europe since my one disastrous trip after Gidget with the girl who’d been my stand‑in. His tone then changed to one of deep disappointment, explaining that I’d be seeing places he wanted to show me, that I was spoiling it for him. When I couldn’t be either bullied or seduced out of my decision, he lashed out: “You don’t expect to win anything, do you?” And I truly didn’t. Never even considered it. But I was going. And when I wouldn’t change my mind, he slammed the phone down, cutting off any more conversation—if that’s what it had been. For the 11‑hour 747 flight to Paris, I sat with Hank Ravetch, feeling wondrously free.

Why is it easier for me to write about the times in my life that felt humiliating or shameful? Is it because those are the things that haunt me? Do I hold on to those dark times as a badge of honor, are they my identity? The moments of triumph stay with me but speak so softly that they’re hard to hear—and even harder to talk about.

I remember my tiny corner room on the eighth floor in the big Carlton Hotel, and how I had packed for the South of France not knowing that the South of France can be freezing in May, and how I would wrap myself in the twin‑size satin duvet and stand in front of the armoire, sliding my few flimsy outfits back and forth, wishing something warm would miraculously appear. I remember how the phones rarely worked when I tried to call the kids, and how I never felt the pressure of Burt since we weren’t speaking. And the French windows opening out onto the Croisette—the promenade along the beach below—and how I’d stand outside on the half‑moon balcony, watching the carnival‑like commotion, and later, the swarm of paparazzi taking pictures of me while I used my Instamatic camera to take pictures of them. I felt like Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday—seeing a whole new world after spending a lifetime locked behind the palace gates.

Before the new Palais des Festivals was built in 1983, films at the Cannes Film Festival premiered in an enormous theater, famously atop 24 majestic stone stairs. The interior of the theater looked like a movie set for The Phantom of the Opera, and those associated with the film were seated for the screening in a grand baroque balcony at the back of this Gothic space. I had never seen the film with an audience, much less with one of the notorious audiences at Cannes—didn’t even know they were notorious until the night before, when Marty and Laddy tried to prepare me. Throughout the dinner they carefully explained that, unlike demure American audiences, this group could react vociferously if they didn’t like what they saw. And if they weren’t booing, then they were walking out in droves. I wasn’t sure how anyone could be prepared for that.

By the time we were finally grouped together in the elaborate balcony I was almost catatonic with nerves, and when Marty, Beau, and I were separated from the others, then seated in the front row, my knees were literally knocking. This was the Queen Mary of theaters and being in the front row of the back balcony felt like we were on the edge of Mount Everest. Not only were my knees vibrating, but I was now flooded with vertigo and the fear that if I stood up too fast, I’d tumble over the edge onto the velvet seats below, dead before the lights even went down. But then they did go down, and the film flickered away.

Every scene felt torturously long, without a single entertaining moment, topped off with the achingly slow roll of the end credits, an endless list that went on and on while everyone in the packed opera house sat, making no noise at all. They didn’t applaud, but hell, they didn’t boo either. They were motionless in their seats. When the studio’s logo finally scrolled by, there was a moment of darkness, and then, suddenly, bright spotlights flared onto the balcony, smack into our faces. And in one connected group, the people below rose to their feet, turned to us, and cheered. They stood applauding for ten minutes. Marty—who had been holding my hand because I was visibly trembling—gently slid away, moving to the side, extending his arm in my direction as he retreated. And I heard the surge that was meant only for me, the sound of that universal appreciation, recognition, and regard for my work. I started to cry.

I won the Palme d’Or for best actress and went on to win every award for best actress that existed in the United States that year. Including the Academy Award.

__________________________________

Excerpted from IN PIECES: A Memoir. Copyright © 2018 by Sally Field. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Sally Field

Sally Field is a two-time Academy Award and three-time Emmy Award winning actor who has portrayed dozens of iconic roles on both the large and small screens. In 2012, she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 2015 she was honored by President Obama with the National Medal of Arts. She has served on the Board of Directors of Vital Voices since 2002 and also served on the Board of The Sundance Institute from 1994 to 2010. She has three sons and five grandchildren.