I spoke with a friend of Robert and Mabel Williams about Negroes With Guns and BLM.

“Why do I speak to you from exile? Because a Negro community in the South took up guns in self-defense against racist violence—and used them.”

These are the opening lines of Robert F. Williams’ book Negroes With Guns (1962), the work that famously inspired Huey Newton before he co-founded the Black Panther Party four years later. I had been thinking of the book for much of the year as I read stories about the nationwide surge in gun sales and wrote about the racialized history of armed patrols.

Unsurprisingly, Black gun clubs across the country have been active in 2020, with some reporting huge membership increases because of pandemic-related anxieties and the psychological toll of widely documented racial violence. People of color who had never thought to purchase firearms before this year have been going to the ranges. According to the National Shooting Sports Foundation, although white people still buy more guns overall than any other racial group in the US, Black customers made up the largest percentage spike in gun sales in the first half of 2020.

The violent deaths of two protestors in Kenosha, Wisconsin last month at the hands of a white supremacist, the increasing boldness of far-right militia groups like the Boogaloo Bois and Proud Boys, and the recent anti-racist reading list boom made me think that Negroes With Guns was probably having another moment. I wasn’t wrong. For a while now, it has been a bestseller on Amazon.

It’s difficult to overstate what a phenomenon this book was. Robert F. Williams and his wife, Mabel, were famous around the world for their confrontations with the Ku Klux Klan in Monroe, North Carolina, where Williams led the local chapter of the NAACP and received support from the NRA to form an armed group called the Black Guard. After local and state authorities falsely accused the Williams family of kidnapping a white couple whom they had actually protected from a mob attack, the couple fled with their children to Cuba, where Fidel Castro granted them asylum. It was in Cuba that Robert wrote Negroes With Guns.

To help contextualize the legacy of the Williams family in this moment, I spoke with a man who knew the couple well. Charles Simmons was born in Detroit in 1941. After serving in the Air Force, Simmons returned to Detroit and attended Wayne State University where he got involved with an influential Black student organization called UHURU (Swahili for “freedom”). Together with his roommates John Watson and General Gordon Baker, Simmons helped lay the groundwork for what would become the most influential Black Marxist-Leninist organization in the world, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. (The story of the League is recounted in Marvin Surkin and Dan Georgakas’ 1975 classic work Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, which is perched high upon my book shelf.)

In 1964, Simmons and other activists were invited to fraternize with young revolutionaries in Cuba, where he met Robert and Mabel Williams. “We had to go half way around the world to get to Cuba because we couldn’t go directly,” Simmons told me. “It was a clandestine trip.” Simmons took a circuitous route from Detroit that included stops in Chicago, Philadelphia, Ireland, Newfoundland, and finally, Havana.

“Detroiters had supported the [Civil Rights] movement in Monroe back in the Fifties,” Simmons said. “When they first heard about it they were helping to send guns to North Carolina. That continued until Robert went into exile.”

Simmons always preferred nonviolence even though he “grew up in a house full of guns.” His grandfather was an active trade unionist who took a pistol to work every day in case there was violence in the factory. Still, Simmons and his peers recognized the Williamses’ contribution to their own cause. For some young activists, Robert in particular was as important a figure as Malcolm X. They had never seen a Black person take such a fiery stance against the KKK and other white supremacist forces.

“We believed that the Black struggle in the US was a part of the global Third World revolutionary movement that was happening,” Simmons said. “We saw the Williamses as a central point of leadership at the high point of connecting us with the international community.”

During the two months Simmons spent in Cuba, where he toured the countryside with Latin American activists—even playing a game of baseball with Castro himself—he established a friendship with Robert and Mabel that would last until their deaths.

“Mabel doesn’t get much play in the books, but she was a co-partner in the struggle,” Simmons explained. “She kept the family together in Monroe during their local war, the underground movement to escape when they all had to go separate directions to get out of the country to go to Cuba. Then keeping them together in Cuba and in China.”

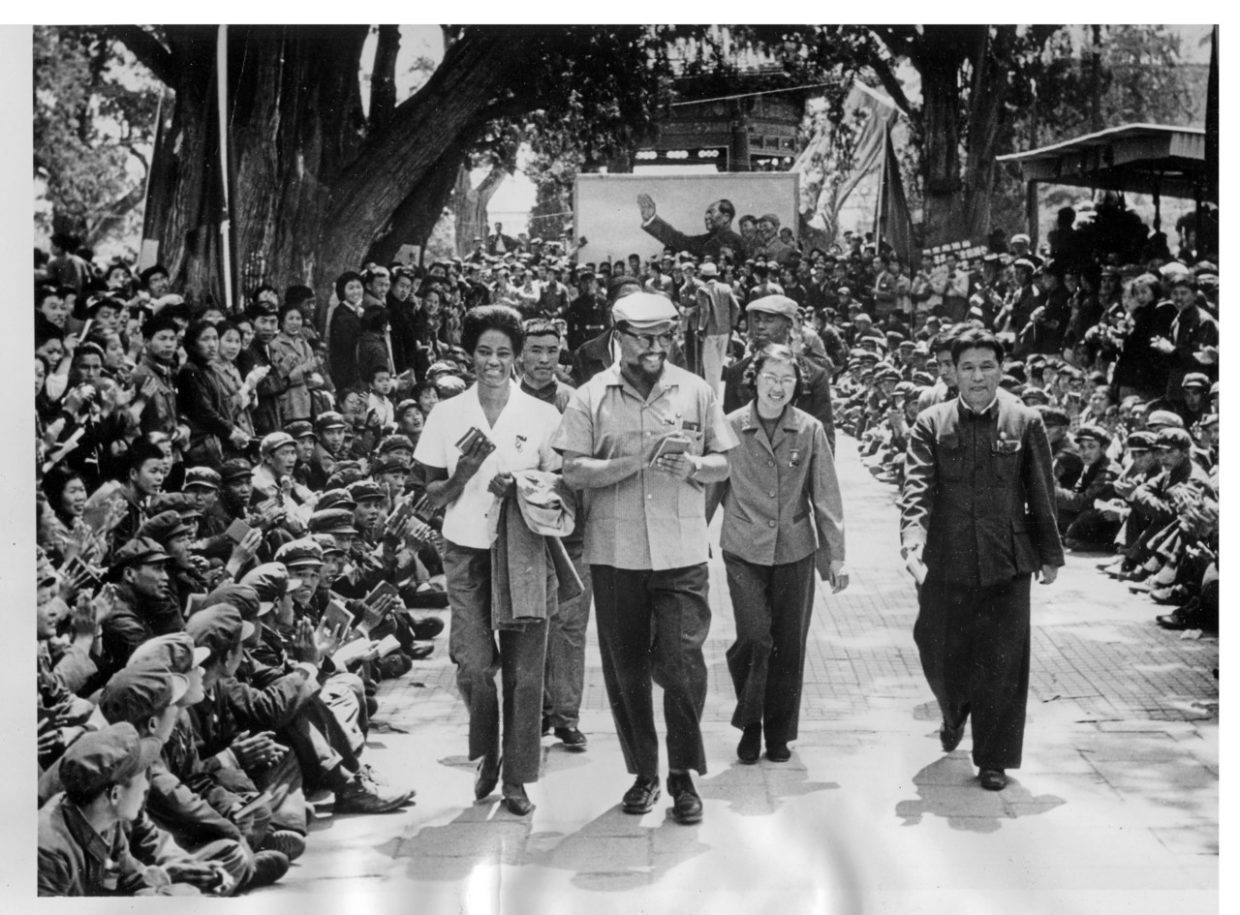

In 1965, Simmons and others from the League were invited to accompany the Williamses to China, where Robert and Mabel would meet one of their biggest fans: Mao Zedong. Simmons didn’t end up making that trip, but he remembers how Robert had been the one to encourage Mao to make a statement a couple of years prior in support of African-American liberation efforts.

Although Simmons believes the decentralized nature of the current Movement for Black Lives is one of its weaknesses, he supports the cause and its embrace of internationalism. He has closely watched this year’s protests in Detroit, where Black activists have supported the Yemen Liberation Movement and the Palestinian Youth Movement.

I asked Simmons how he saw the spirit of Robert and Mabel Williams manifest today.

“I see this video of these Black folk in Atlanta marching,” Simmons said in reference to a group of New Black Panthers protesting the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha. “They had their uniforms and these long rifles. Now I just wonder how prepared they are to come out in the open like that. That’s a big step. It could be very harmful to them and people in general. Because we are numerically a minority in some places, and we’re not organized as an independent group, the [white] folks still have the big guns and the organization and the financing.”

“Rob told us that even in Monroe, and even when they got armed, there were, among the Black men—and many of them were veterans—there was still a fear of confronting white people. They had to have something extra to express or identify with Black leadership going up against the Man . . . It’s another level of struggle to say you’re going to go out and fight the white folks. That was two generations ago. I don’t know how much that has changed.”

Aaron Robertson

Aaron Robertson has written for The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. His translation of Igiaba Scego's novel Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019) was shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize and Best Translated Book Award.